Update 23 December 2022: The Government has now published a consultation that advances the development management proposals in the Bill and the policy paper published in May 2022; Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill: reforms to national planning policy

The focus of press releases regarding

The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill has been on street votes, consultation, plan-making, digitisation, design and provision of infrastructure. The Development Management provisions are less obvious, but just as important, and would slot in quickly and easily to the existing English planning system. Some also have an immediacy to them, as they will not require regulations, other than commencement regulations, to give them full effect. Others are changes referred to in a policy paper about the Bill and will not form part of the Bill itself.

The proposed changes to the development management system discussed in this blog are:

-

A new procedure to amend planning permissions - including their descriptions of development

-

The use or lose it provisions, designed in response to suggestions of land banking

-

Changes to section 38(6), which currently requires decisions to be made in accordance with the development plan, unless material considerations indicate otherwise

-

Potential increase to planning application fees

-

Changes to enforcement legislation, including all breaches being subject to enforcement for up to ten years

-

Changes to heritage legislation

-

Making pavement licence applications permanent

Section 73B – new route to vary a planning permission

Section 73 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (TCPA) allows applications to be made for permission to develop without complying with a condition previously imposed on a planning permission. It is commonly used to make minor material amendments to planning permissions. The Finney case, discussed in greater detail

here, confirmed that section 73 cannot be used to alter a description of development. Therefore, multiple applications are often now needed where a minor material change to a scheme is proposed. To change a description of development, it is currently necessary to submit a s96A application, which should be approved if the change is non-material.

The Bill would introduce Section 73B, a new route to vary an existing, express, original planning permission when making non-substantial changes, including to the description of development. This new route would only be permitted if the local planning authority (LPA) is satisfied that the changes will not create a substantially different permission. No further detail has been provided on what would constitute “a substantially different effect”. Under Section 73B, the authority should limit its considerations to the ways in which the variation would differ in effect from the existing permission and it will not be possible to use the new provisions to extend the time for implementing a permission. Section 73B could also be utilised to make changes to permission in principle. It appears that section 73B creates a new planning permission, thus meaning either the original or changed scheme can be implemented – unlike s96A, which amends a scheme and only the amended scheme can be implemented. The provision appears to be designed for changes in the course of construction and cannot be used to amend retrospective planning permissions. Related to this purpose, s73B would allow for existing section 73 planning permissions for minor material changes to the original planning permission, to be taken into account when determining s73B applications – albeit without permitting the amendment of s73 planning permissions. This might mean that a s73B permission creates single alternative scheme to the original, incorporating the preferred previously permitted changes. Such an amendment would probably still require the s106 to be varied, unless it already incorporated such amendments. One might assume that the CIL Regulations would be amended to expressly take into account section 73B, the absence of which could lead to a few LPAs refusing to entertain applications that would result in changes to floorspace, as they do with s96A applications that would do so at present.

Commencement and completion notices – use it or lose it

Commencement notices

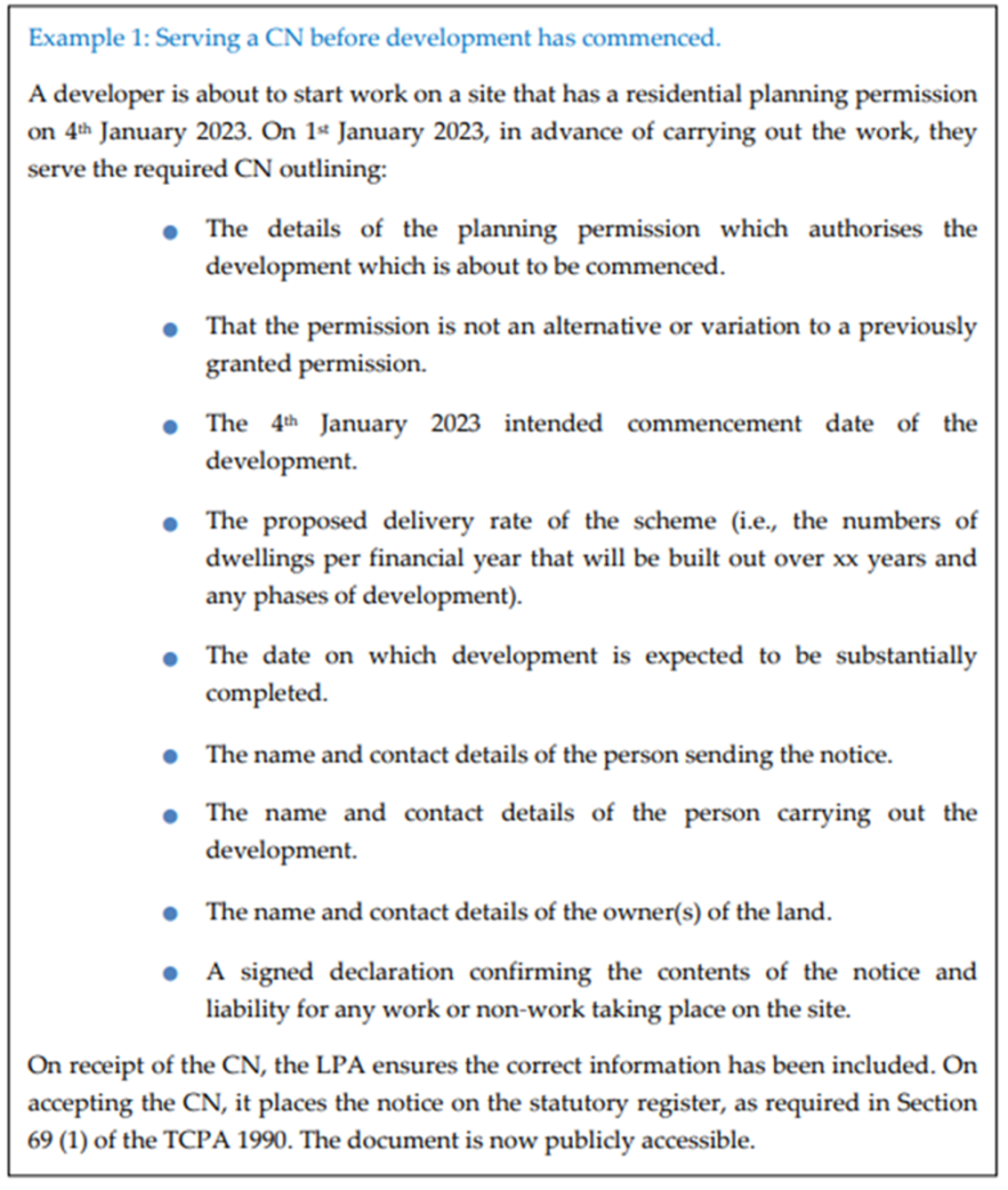

Clause 99 would insert a new section, 93G (Commencement Notices), into the TCPA 1990. This new section would require those carrying out certain as-yet-undefined development types to serve a commencement notice to the relevant LPA, before any development has taken place. This notice would require the expected start date of development, the details of the planning permission, the proposed delivery rate of the scheme and other relevant information (as outlined in the explanatory notes of the Bill).

The example in the explanatory notes of the Bill (see figure 1 below), suggests that the provision would most likely apply to large scale residential schemes, to prevent perceived land banking by developers.

Figure 1

Completion notices

A new power would be given to LPAs, to serve a completion notice on a planning permission for development which has commenced, but which in the LPA’s opinion will not be completed within a reasonable period. A completion notice could be served no earlier than 12 months after the date stated in a planning condition for implementing a planning permission (i.e. at least 12 months after the development commencement deadline). A completion notice would set out a time limit (“completion notice deadline”) after which the planning permission would cease to have effect for any unfinished parts of the development. The deadline for compliance with the completion notice would be no sooner than 12 months after the notice was served. There would be a process for appeals against the serving of a completion notice. Given that the time period for commencing a development cannot be altered by any existing or proposed procedures for amending permissions, the date from which a completion notice could be served would not change if a permission was amended.

The new completion notice power, under section 93H of the TCPA, would not require the Secretary of State to confirm when a completion notice can take effect in England. Under existing law, a section 94 completion notice can only take effect once it has been confirmed by the Secretary of State. Existing Section 94 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (termination of planning permission by reference to time limit: completion notices), would only continue to apply in Wales.

The Bill, its explanatory notes and its associated policy paper do not state that completion notices could only be served on certain types of development, whereas commencement notices would be limited in their coverage. However, the change in legislation is linked to lobbying for “use it or lose it” measures and the Housing Minister made clear that the provisions are intended to be used together, during a Parliamentary debate [1]:

“There are measures in the Bill to try to address build-out rates, which are an important element that we have to tackle. Under the Bill, it will be necessary to supply the local authority with a commencement notice, an agreement on the number of houses that will be built each year and a completion notice. We are absolutely on this, and I assure my hon. Friend that we will do everything we can to ensure that the houses that have got permission are built.”

The continued push for use it or lose it provisions comes despite land banking claims being routinely debunked –

see this blog by Matthew Spry.

Perhaps completion notices are applicable to all development to mask this provision being aimed at land promoters and larger housebuilders?

A related provision, in terms of the desire to monitor land control and build out rates, would “improve transparency about the ownership and control of land” according to the Bill’s policy paper. The clause permits the Land Registry or equivalent “to collect information on the ownership of land, of relevant rights concerning land and others with the ability to control or influence (directly or indirectly) over the owner of a relevant interests or rights relating to land” – i.e. to centrally record the options taken on land.

Role of the development plan in decision making

Clause 83 of the Bill relates to the role of the development plan and national policy in England.

Currently, the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 (PCPA) allows determinations to diverge from the development plan where material considerations indicate that this is justified. S38(6) of the PCPA would be amended so that determinations would be made in accordance with the development plan and national development management policies unless material considerations strongly indicate otherwise.

These changes are covered in more detail

here, but from a development management viewpoint the addition of the word ‘strongly’, would result in greater weight being given to the development plan than is currently the case, while also immediately placing national development management policies above other national policy. Given these proposed changes, a review of the NPPF is also expected to follow. As with other development management proposals, this change would not come into force in Wales.

Consultation on increasing major application fees by more than a third

Alongside the publication of the Bill, the Government has committed to increasing planning fees for major applications by 35% and minor applications by 25%. However, they have made clear that an increase in fees must coincide with a better planning service for applicants. These proposed changes will first be subject to a consultation.

Enforcement – four year rule to be upped to ten for all breaches

Chapter five of the Bill refers to the changes for Enforcement of Planning Controls. This the introduction of several private members Bills relating to enforcement (

see Lichfields Planning News, October 2021).

Of particular note, LPAs would have ten years to take enforcement action against unauthorised development for building, engineering, mining or other operations in England. This would be development in, on, over or under land up to ten years after the date on which the works were substantially completed. The time period for enforcement action will remain four years in Wales. The time period for the duration of temporary stop notices has also been increased in England to 56 days, from 28 days previously. This would remain 28 days in Wales.

English LPAs would have the power to issue enforcement warning notices. These notices could be issued where a breach in planning control has occurred, but the LPA judges that there is a reasonable prospect of planning permission being granted for the development if a planning application was submitted. If the application is not received within the specified period, the LPA could take further enforcement action.

There would also be an extension of the circumstances in which the ability to lodge a ground (a) appeal against an enforcement notice issued in England is removed so that there is only one opportunity to obtain planning permission retrospectively after unauthorised development has taken place.

In Section 174 (2) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, a ground (a) appeal is submitted on the grounds that that planning permission should be granted for what is alleged in the enforcement notice (or that the condition or limitation referred to in the enforcement notice should be removed). New subsection (2AC) of the Bill explains the different circumstances in which a related application ceases to be under consideration. Subsection (2B) clarifies the day on which the application ceases to be under consideration for the purposes of calculating the two year period in which an enforcement notice must be issued if a ground (a) appeal is to be prohibited.

Furthermore, the Secretary of State would have new power to dismiss an appeal in relation to an enforcement notice or an application for a lawful development certificate in England if the appellant is deemed to be causing undue delay to the appeal process. The appeal could be dismissed unless the appellant takes the action specified in the notice within the outlined period.

The penalty for noncompliance with a breach of condition has also been increased to an unlimited fine, as has noncompliance with a section 215 completion notice (which are rarely issued at present, and different to the proposed s93H completion notices, see above). It also increases the maximum daily fine in England to the greater of either one tenth of a level 4 fine (currently £2,500) or £5,000.

The Secretary of State would have a new power, via regulations, to provide relief from enforcement of planning conditions against a developer or individual, for non-compliance with specified planning conditions or limitations, for a specified period. This would allow greater flexibility in the enforcement regime. Instead of issuing specific persuasive but non-binding guidance regarding taking enforcement action, for example as the Government did regarding delivery hours conditions etc.

during the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, the Government would be able to rely on these new laws.

Heritage

With regard to heritage, the Bill would insert a new section ‘duty of regard to certain heritage assets in granting planning permission or permission in principle’ into the TCPA 1990. New section 58B (1) would specify that a local planning authority or the Secretary of State must have special regard to preserving or enhancing a heritage asset or its setting when considering planning applications in England.

“Heritage assets”, would include Scheduled Monuments, Protected Wreck Sites, Registered Parks and Gardens, Registered Battlefields or World Heritage Sites, so that they would have parity with listed buildings and conservation areas in law, as well as the existing policy parity.

The Bill would also amend section 16 of the Listed Buildings Act to require consideration of preservation or enhancement, instead of solely preservation, when determining listed building consent applications.

Another proposal is to amend the Listed Building Act so that a temporary stop notice could be issued on work to a listed building for up to 56 days while also making it an offence for breaching this notice.

The proposed ‘removal of compensation for building preservation notice’ is expected to have significant impact. LPAs can serve a Building Preservation Notice (BPN) on the owner and/or occupier of a building, which is not currently listed, but is considered to be of special architectural or historic interest and is at risk of being demolished or changed, which would affect this status. Currently, under section 29 of the Listed Buildings and Conservation 1990 Act, a person who has an interest in a building which has been served a BPN can make a claim to the LPA for compensation for any loss or damage as a result of the BPN. The Bill would amend the Listed Building Act and remove this right.

High Streets and pavement licences

As discussed in greater detail in this blog, the Bill proposes a new power to instigate “high street rental auctions” of selected vacant commercial properties in town centres and on high streets which have been vacant for more than one year.

The Bill also sets out when a town centre may be designated. The Bill defines “high street use” too – essentially uses that the Government is looking to protect or considers desirable, with no reference to use class. This is not directly relevant to development management, but it is interesting to see the uses that the Government would like to actively encourage on High Streets.

The Bill would also make permanent, subject to some changes, the measures that facilitate pavement licensing which were first brought in as the high street reacted to COVID which are outlined

here.