The media’s silly season has started early. On 23

rd June, the

i published an article

[1] alleging land hoarding by UK house builders. This is well-trodden ground, but with the added dimension that the Secretary of State directly endorsed the charge:

"Gove slams housebuilders hoarding almost a million plots of land as ‘completely unacceptable’

The top ten housebuilders alone have 700,000 building plots lying idle as the housing shortages continues to worsen

Housing secretary Michael Gove has slammed developers for sitting on land rather than building new homes after an investigation by i found they are hoarding more than a million building plots.

Known as land banking, the practice has led to calls from politicians and experts to force developers to increase construction numbers, be taxed on unused land, or face compulsory purchase orders in an effort to increase construction and ease the UK’s worsening housing crisis.

The calls come as new home completions have hit a 15-year low."

The Secretary of State’s shadow also implicitly accepted the i’s premise:

“Shadow Levelling Up Secretary Lisa Nandy went further and told i that Labour would allow the compulsory purchase of sites within the vast land banks held by developers in order to build social housing.

‘The Tories have sat by for 13 years as hard-working people have their aspiration held back, while speculators frustrate building and squeeze the supply of affordable homes working people need in expectation of big unearned profits,’ said Nandy.”

Where to begin…

The landbanks of UK housebuilders

The i’s report included the following nugget:

"Exclusive analysis by i shows that the top 10 housebuilders listed on the London Stock Exchange are sitting on 700,000 plots, many of which have planning permission.” (my emphasis)

The word ‘many’ is doing a lot of heavy lifting here.

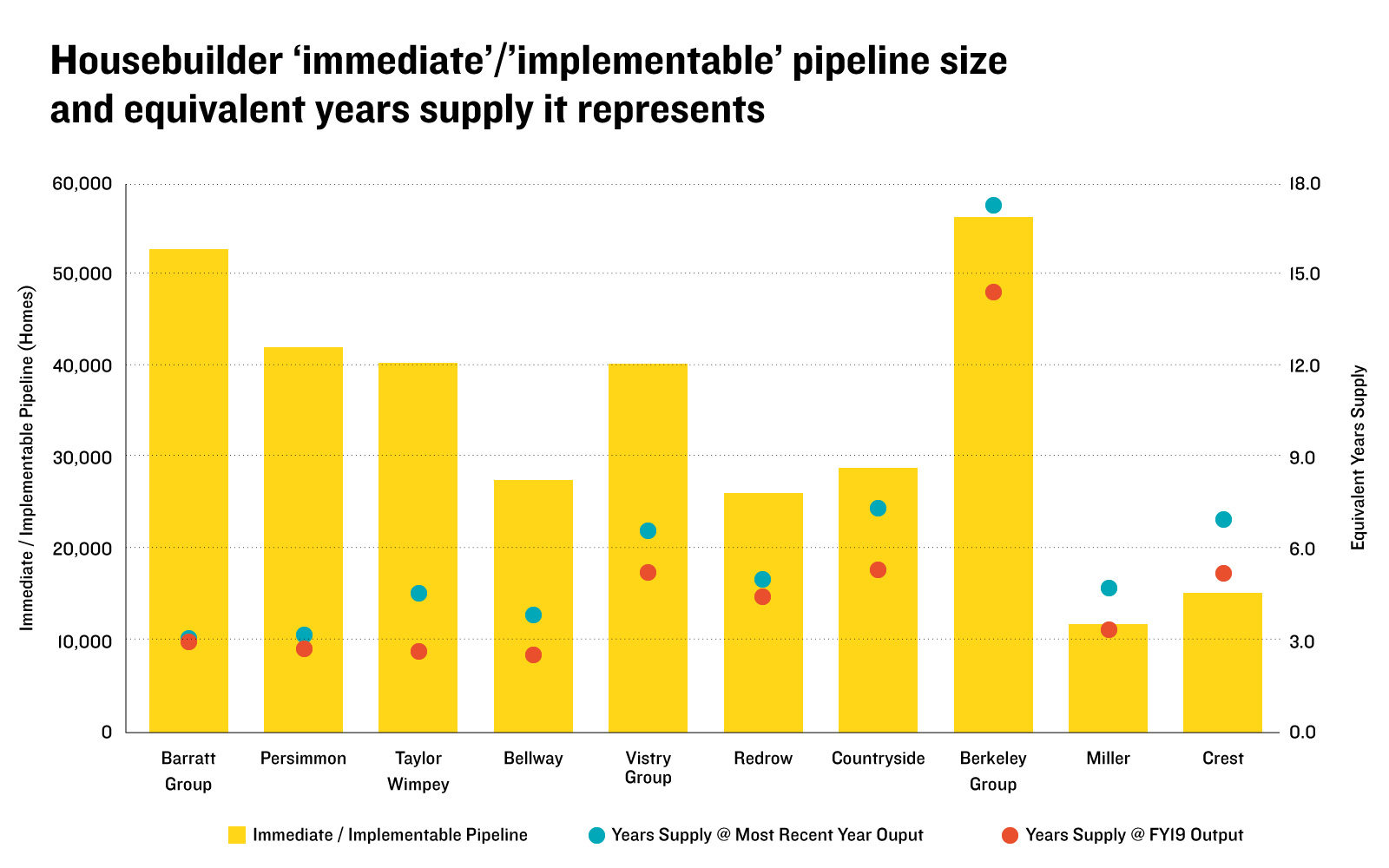

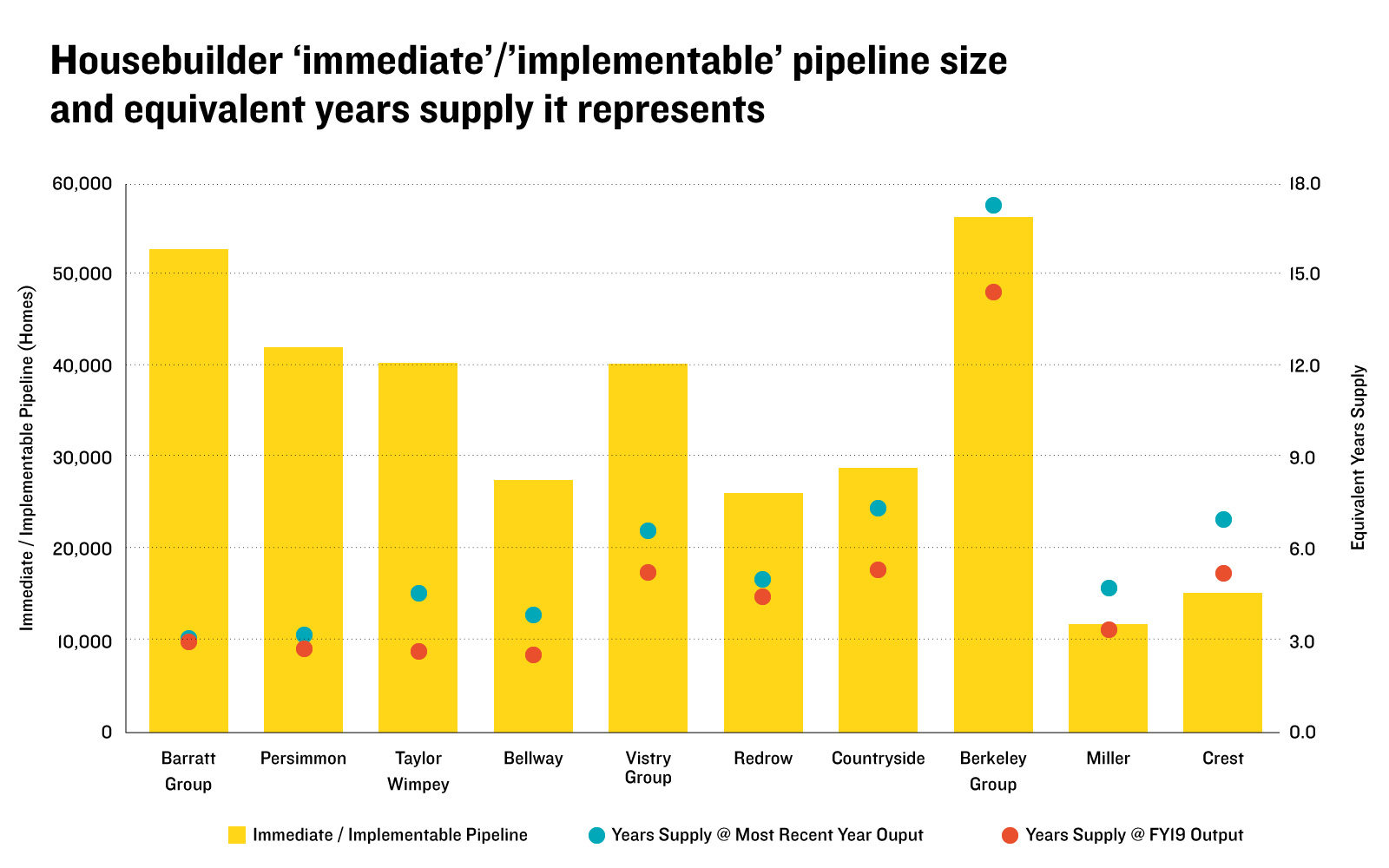

Feeding the Pipeline - our 2021 report for the HBF and LPDF – analysed the land banks of the top 10 housebuilders. It identified that the immediate/implementable land bank (with planning permissions) amounted to just 340k plots, and excluding Berkeley as a clear outlier

[2], those businesses hold a pipeline equivalent to 3.3 years, and the three largest – Barratt, Persimmon, Taylor Wimpey - held implementable pipelines of 3.0, 2.8 and 2.6 years. Although this report is based on corporate reporting from summer 2021, the basic findings remain extant.

Our analysis identified a further 210k plots that were “proceeding to planning” at “outline” or “not implementable”. This is the land bank that will be converted into immediate/implementable plots in subsequent years. Some builders – not all - then report a strategic land pipeline that has no planning status at all (and thus is incapable of being developed unless a LPA chooses to allocate it in a Local Plan), and it is this that gets the i to its 700k headline.

In combination, and again excluding Berkeley as an outlier, the top ten builders had an ‘immediate/implementable’ plus ‘proceeding to planning/not implementable’ pipeline equivalent to 5.3 years of their output.

The NPPF requires local authorities to maintain a five-year land supply of deliverable

[3] land (plus a buffer). So, we can see that the large housebuilders have land banks that are largely at the very minimum of what national planning policy would expect them to have.

Why would you need a five-year pipeline?

It takes time to bring land through the planning system. We have a plan-led system (no laughing at the back) where there is a statutory assumption that plans are reviewed every five years. Sites are allocated in local plans and then have to secure planning permission, typically in outline and then in detail. Once permission is granted, conditions have to be discharged and there needs to be site preparation, ground works and then homes are built.

Even in a smoothly-operating system, this would take time. And of course, we have a system that is anything but. Just to give some examples:

-

A developer with a site in Welwyn Hatfield would have seen a draft local plan

[4] consulted upon in Jan 2015; Eight and a half years later, the plan is still being examined as Inspector and LPA tussle over soundness of the strategy.

-

In Spelthorne, the local plan process began in 2014; examination hearings in began on 23

rd May 2023, but two weeks later, the Council asked the Inspector

[5] to pause the process to

“allow time for the new council to understand and review the policies and implications of the Local Plan”

-

In Tandridge, the Local Plan was initially consulted on in 2015

[6], submitted for examination in 2019 and is still ongoing. To respond to the delay, the Council adopted an interim policy that indicated it would look favourably on planning applications on draft allocations. CALA submitted an application for just that. The Council refused it

[7].

At its simplest level, any house builder with an immediate land bank of less than three years would run out of plots and have to stop building because they would not be able to replenish it with new sites taken through the planning process. A halt to building would prevent them from achieving sustained level of production and labour demand, and lead to peaks and troughs in capital outlay that would make their business impossible.

This is the opposite of what the housebuilders advise their shareholders they want. Of the top 10, all but one had specific aspirations in their corporate reporting from 2021 to grow output volume and/or outlets.

Research by ChamberlainWalker Economics for Barratt Developments

[8] explored the role of housebuilder pipelines, estimating that housebuilders would need to hold pipelines of at least 5.7 years to secure annual growth in completions whilst ensuring business security – if a housebuilder increased output without increasing its pipeline, it would speed towards the cliff edge, exhausting its supply of implementable sites.

Would housebuilders have a financial incentive to land bank?

The allegation of ‘hoarding’ assumes that there is a financial benefit to limiting supply and holding onto land without building on it.

But housebuilders make a profit by selling homes they have built on land they have acquired from the landowner for that purpose. Sitting on acquired land without building on it is harmful as it ties up resources, limits the return on capital employed, and means they have less resource to invest in new projects.

When the market demand supports it, housebuilders have typically boosted build out and sales rates. A recent report by Savills for Richborough Estates and the LPDF

[9] found:

"The average sales rate per outlet across our sample of major housebuilders was around 0.62 to 0.68 between 2003 and 2007, before it fell sharply during the GFC to hit a low of 0.40 in 2008. Since then, the average sales rate has gradually increased, reaching a fairly stable level of approximately 0.73 again between 2015 and 2019. Sales rates then fell during the first Covid lockdown, before rising to an average of nearly 0.87 during 2021 and 2022."

My blog from 2021 –

Use it or Lose it: the taxing problem of undelivered homes – considered the issue of unimplemented permissions and revealed how a succession of reviews have considered and rejected the idea that housebuilders hoard land.

But it turns out it is not just housebuilders who stand accused. In its article -

'Michael Gove's housing agency accused of land banking' - the Telegraph

reported that:

"Michael Gove's department is sitting on enough land to build more than 250,000 homes, analysis suggests, after the Housing Secretary criticised developers for hoarding hundreds of thousands of plots.

Homes England, an agency, tasked with supporting the development of new affordable homes, controls a portfolio with enough space for 279,000 houses"

Naturally, Homes England pushed back strongly on the allegation that it was hoarding, claiming: "as soon as the land is ready and outline permission is received, we engage housebuilders to build out as quickly as possible. Land banking suggests we do nothing, but this couldn't be further from the truth."

That the charge against house builders could be similarly made against the public body that is charged with speeding up housebuilding shows the real answer lies in the application of Occam's razor - the simplest explanation is actually true: any organisation involved in housebuilding needs a pipeline of sites at different stages of the planning process to manage the inherent risks and timescales associated with residential development. Counting a stock of land (whether it is the housebuilders' 700k, or the 279k controlled by Home England) without thinking about the width of the planning pipe (and its tendency for blockages) or the rate of flow through it, will draw entirely misconceived conclusions.

What does the recent housing permissions data tells us?

So, how do we boost supply?

All the evidence is that that rather than berating housebuilders for having a pipeline that is the minimum needed to sustain a sensible residential development business, there needs to be an increased number of outlets with planning permission.

Feeding the Pipeline suggested that achieving 300k per annum would require each District in England to grant permission for an extra 4-5 medium-sized sites per year on top of the rate of approvals that have sustained recent rates of delivery. (Of course, it would also be helpful if these sites were in the parts of the country where there is the greatest need for new homes.)

Unfortunately, the recent published data on planning permissions

[10] suggests things are heading in the wrong direction. The Q1 2023 rolling annual total of homes granted permission (at 269k) is down 11% from the same period last year, the lowest since Q1 2015, and five of the past six years have seen a reduction.

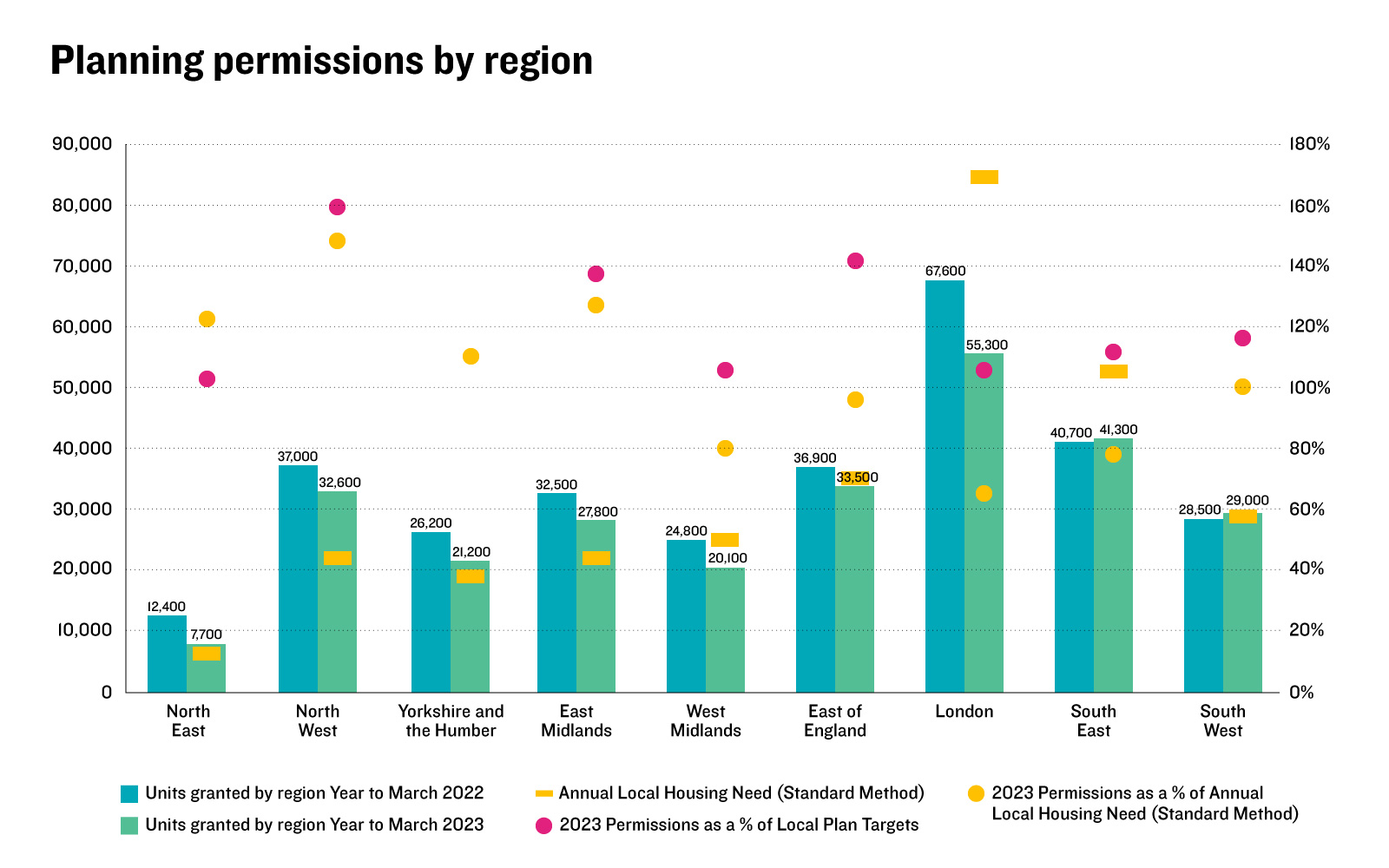

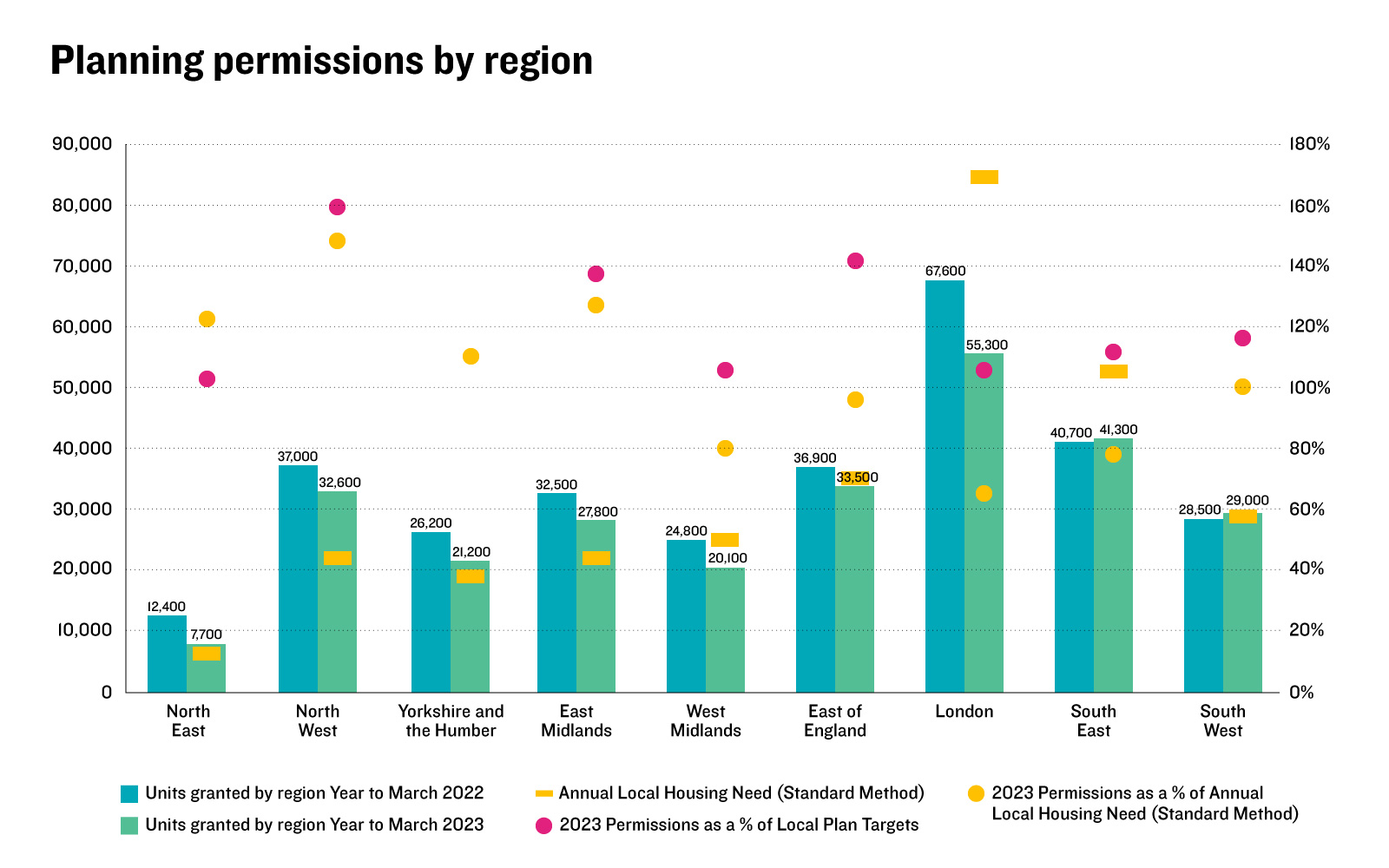

The chart below shows the figures broken down by region.

Over the past year, the biggest percentage falls in permissioned homes were in the North East (-38%) with Yorkshire and the Humber, West Midlands and London seeing falls of 18-19%. The South East and South East saw a static flow of permissions. However, the key issue is that in London, West Midlands, East of England and the South East, the flow of permissions falls well below the number of homes demanded by the Standard Method (at 65-80% of the SM figure).

Because permissions granted each year will include a proportion (perhaps 10-15%) that will be superseding/amending an old permission (a figure of c.30% might be expected in London based on a case studies of London permissions), and circa 3-5% (and perhaps more in London) that will lapse or stall

[11]; a flow of permissions well in excess of the Standard Method in every region would be needed to align with the 300k annual ambition. That it falls well below this level suggests we are heading on a downward trajectory of housing delivery.

Conclusion

That there are c.700k plots in the land banks of large volume house builders “many with permission” is evidence not of cynical land hoarding but of what a sensible residential development business would need to maintain house building in an environment where it takes at minimum 3-5 years for a site to move from acquisition, securing an implementable planning permission, opening it up and then building homes. Analysis in 2021 showed the immediate/implementable land banks were just over three years, with a further two years of land not yet implementable but progressing through planning.

The current slow down will impact on sales rates and push some of these numbers out, but equally, we can see the flow of permissions is also reducing (it having decreased in five of the last six years) making it less likely that the pipelines will be replenished at the same rate.

Looking beyond the unfortunate failure of the i to correctly interpret the figures it produced, the bigger disappointment is the political exhumation of the allegation that house builders are hoarding land. It seems like a distraction from the real challenge to housing delivery: the collapse in local plan making, the fall in permissions for housing, and the sustained under-shooting of housing delivery in areas where homes are most needed. Remedies on these fronts are what is most needed right now.

[1] The original i article is here

[2] The report states: “Berkeley Group - an outlier among the ten - they report ‘plots’ (homes) on all land holdings where a ‘backstop planning position’ exists, itself not necessarily consistent with the ‘immediate’ pipeline definition used by others. Their pipeline also includes long-term complex regeneration developments, many already under construction but where activity is expected to continue over many years and decades, such as at their Woodberry Down (5,500 homes) or Kidbrooke Village (5,000 homes) regeneration projects in London. Berkeley’s average site size was 659 homes, more than triple the median of 216 homes we recorded across the other nine housebuilders’ site sizes”

[3] Deliverable is defined by the NPPF as: “To be considered deliverable, sites for housing should be available now, offer a suitable location for development now, and be achievable with a realistic prospect that housing will be delivered on the site within 5 years.”. Having an allocation or outline permission is not automatically assumed to mean that the site will be capable delivering housing within five years.

[4] Regulation 18 Local Plan Consultation

[5] Letter from Spelthorne to the Inspector is here

[6] A Reg 18 Issues and Approaches Consultation

[7] CALA was successful at the subsequent appeal, at which Lichfields gave the planning evidence.

[8] The CWE report is here

[9] The Savills report is here

[10] The DLUHC Planning Applications Statistic Release for January to March 2023 is here

[11] These percentages are drawn from Tracking Progress: Monitoring the build out of housing planning permissions in five local planning authority areas