The insertion of reference to the quality of scheme design into Paragraph 11d of the July draft NPPF was seen by some as wariness from Government that the increase in planning applications needed to boost the supply of housing might somehow result in a diminution of scheme quality. But surely the existing NPPF provision on design already prevents that?; especially since the strengthening of the need for design quality in the 2021 iteration of the Framework, which has been maintained thereafter.

The current paragraph 139 states “Development that is not well designed should be refused.” This is the NPPF’s categoric policy message on design and a clear steer from the previous government that despite the urgency of the housing crisis, national policy would not permit it to be solved with poor design. This requirement to deliver well designed schemes was strengthened in the NPPF in the July 2021 iteration (paragraph 134) and is maintained in the September and December 2023 updates at paragraph 139. To support well designed schemes, there is a raft of guidance/tools on good design which ultimately feed into applications including Building for a Healthy Life 12, the National Design Guide and National Model Design Code.

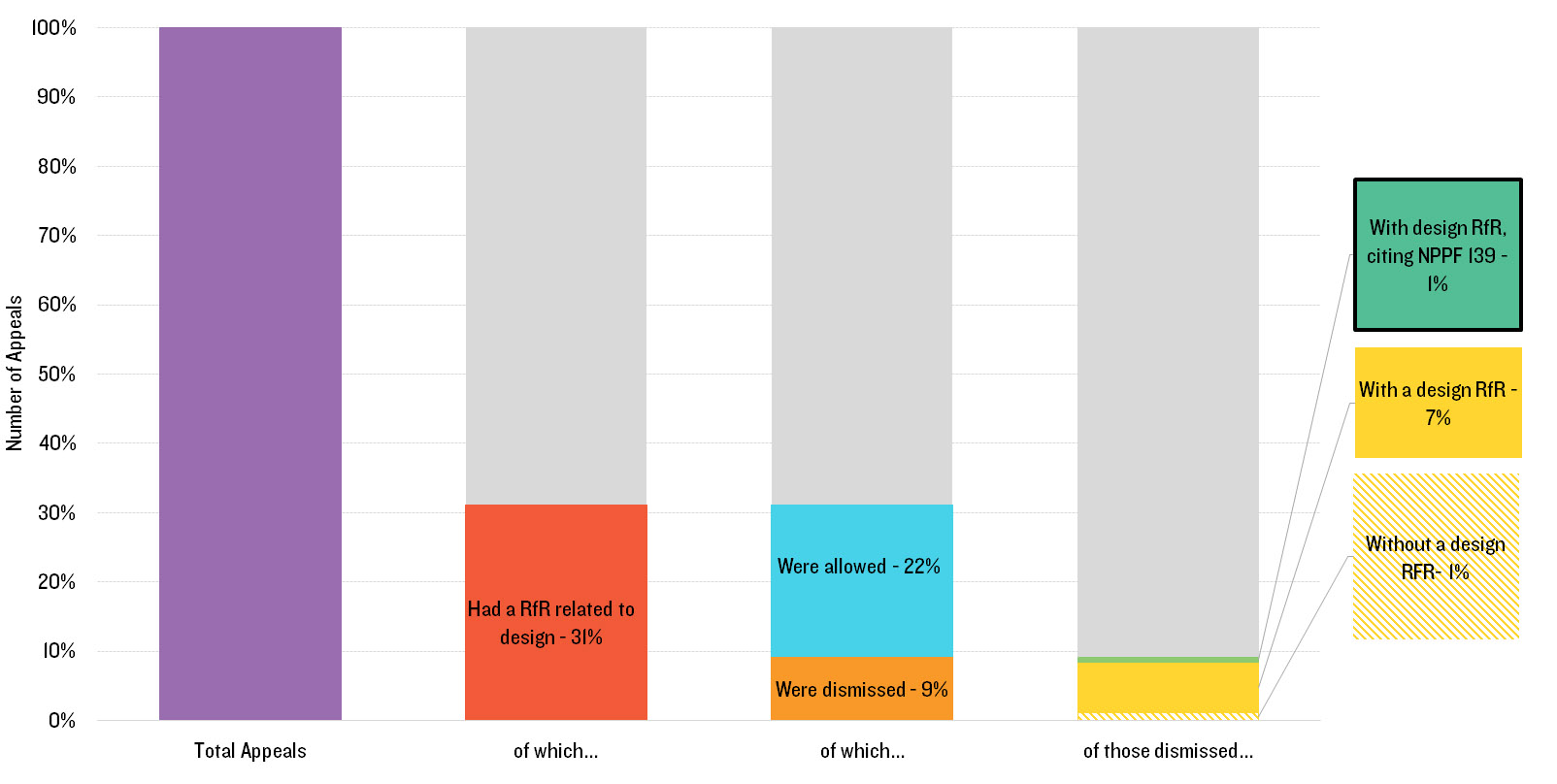

To analyse whether the NPPF’s current provisions on design quality has impacted on how design is addressed in submitted planning applications, or if schemes are now routinely being refused for not delivering well-designed places, Lichfields has reviewed a sample of 270 planning appeal decisions for 50 or more homes since the adoption of the July 2021 NPPF

[1].

Initial key findings

Of the sample of 270 appeals reviewed, we found only 30% where design was conceivably one of the main issues for the appeal inspector and in some instances the Secretary of State, (SoS) to grapple with. This implies design even in its broadest sense is not one of the most prevalent reasons for schemes going to appeal, most certainly not since July 2021. We explain below that in fact most of the references to ‘design’ relate to the potential impact of schemes on the character and appearance of the area, i.e. landscape and townscape impacts rather than the design of spaces and buildings.

But even on this broad definition, of these appeals, 70% were allowed, two by the SoS. This means any design issues perceived as problematic locally were not agreed by the appeal inspector or SoS when they examined the evidence.

It is also of note that of those appeals which were allowed, just under half were refused against officer recommendation at the local level, and on average a further ten months was added to their determination. This means that using their professional planning judgement, design was not something the case officer thought was a reasonable basis on which to refuse the scheme (despite the clear NPPF policy hook to do so if justified). Arguably, these schemes should not have ended up at appeal at all, incurring significant costs to all parties, not least the local planning authority. Adding almost a year’s delay to the determination of these applications will have been frustrating where applicants had invested time in a pre-application design review process – as some of these schemes were. Conversely, for the those appeals dismissed where the Inspector agreed with the local concern about design (in its broad sense), 60% were refused by case officers.

Of the smaller number of schemes dismissed on design grounds

[2], only one in five were applications made by the biggest five-volume housebuilders

[3].

80% of applicants were smaller housebuilders, land promoters or other bodies/individuals. The low number of appeals dismissed where volume housebuilders were the appellant is perhaps an indication of effective early engagement, use of design tools, etc.

Furthermore, of all the schemes where design was debated as a main issue at appeal, just over a third were allocated, or an emerging allocation, in a local plan. Of these sites, more than three quarters went on to be allowed.

Finally, we have also considered the prevalence of design codes and whether these were determinative in appeal decisions. Ultimately, we found that of all appeals where design was a main issue for debate, less than 10% of the local planning authorities (LPAs) had an adopted design code in place.

BUT, what is design?

In undertaking this analysis, clearly design is not an issue which is easily categorised. In many of the appeal decisions reviewed, commentary and analysis about scheme design (layout, heights, building design etc.) is in fact conflated with narrative about impact on the character and appearance of the area, impact on the character and appearance of the countryside, and finally in some instances into impact on landscape character. Ultimately, the precise reason for refusal is not always clear, and it may be that development of an open field is too harmful to the character and appearance of an area, regardless of the actual design of the scheme put forward. Indeed, in the case of outline applications, there is not usually a significant amount of design material to make judgements against, given this is reserved. This was borne out in a number of appeal decisions whereby inspectors found proposals were acceptable with regard to detailed design, subject to control by future reserved matters and condition submissions.

Appeals dismissed clearly on the grounds of poor design of the development proposed (e.g. the design quality of spaces and buildings) were few and far between, with the vast majority primarily relating to character and appearance of an area/the countryside/the wider landscape. If the proposed development truly was not well designed, you would expect the appeal inspector to have cited the NPPF para 139 (or previous 134) or the beauty and quality expected by the Framework for design. However, only three of the dismissed appeals make this reference. Much more common is reference to local plan policies, with some conflation of topics as set out above.

This means that the NPPF’s very clear policy requiring poorly designed schemes to be refused – triggered a dismissal in just 1% of all appeals in this sample.

What does this mean?

Ultimately, this initial analysis shows that schemes which are “not well designed” are not a prevalent feature of planning appeals coming forward for major housing schemes. But even where they are, the NPPF provides the policy hooks necessary to dismiss them on appeal. There is no evidence to suggest the NPPF as a whole is routinely permitting poorly designed schemes. In that context, there would not appear to be any case for changing how design matters are addressed via national policy as was consulted upon back in July 2024, and risk adding a layer of confusion to the application of NPPF Paragraph 11d. Indeed, the application of the tilted balance owing to unmet housing need does not outweigh harm associated with poor design in the current NPPF, which perhaps demonstrates that the policy is working. An environment with a greater prevalence of 5YHLS deficits will not change this.

The research also specifically shows that only a very small number of appeals are refused on the grounds of poor design. This infers that applications on sites that are submitted ahead of a local plan (i.e. not allocated) are no less well designed than applications on sites allocated in a local plan. Furthermore, it does not appear that large volume house builders are typically submitting poorly-designed schemes.

What is of interest, and is of relevance to the debate about reforming planning committees covered in the weekends press and in

The Planning Reform Working Paper published today, is the clear relationship with the application of design as a reason for refusal in applications which go against the recommendation of case officers. This aligns with Lichfields previous research

Refused for Good Reason, which found that in 24% of appeals impact on character of areas and in 22% of appeals height/scale of development were added as reasons for refusal to applications refused against planning officer recommendation.

Footnotes

[1] c.50% of these appeals determined in this period

[2] Of those appeals where design was a main issue, two appeals were dismissed for reasons other than design, i.e. design did not form a reason for refusal by an appeal inspector.

[3] BarrattRedrow, Taylor Wimpey, Bellway, Vistry and Persimmon

Header image credit: Antony Hyson Seltran on Unsplash