There has been plenty of conjecture about the proposed NPPF changes and whether the Government’s 1.5 million delivery target is within reach, but what hasn’t hit the headlines is the implications for our major urban areas. With a renewed emphasis on ‘brownfield first’ being the starting point, many urban Council’s will need to work harder than ever to provide the homes that society needs.

On the one hand, the NPPF (new §122) introduces an “acceptable in principle” support for proposals on brownfield land within settlements for homes and other identified needs, but conversely, the new Standard Method for calculating housing need sees a reduction in targets across the majority of the country’s largest urban areas. Are these “acceptable in principle” sites going to need to work harder than ever too? The numbers suggest so.

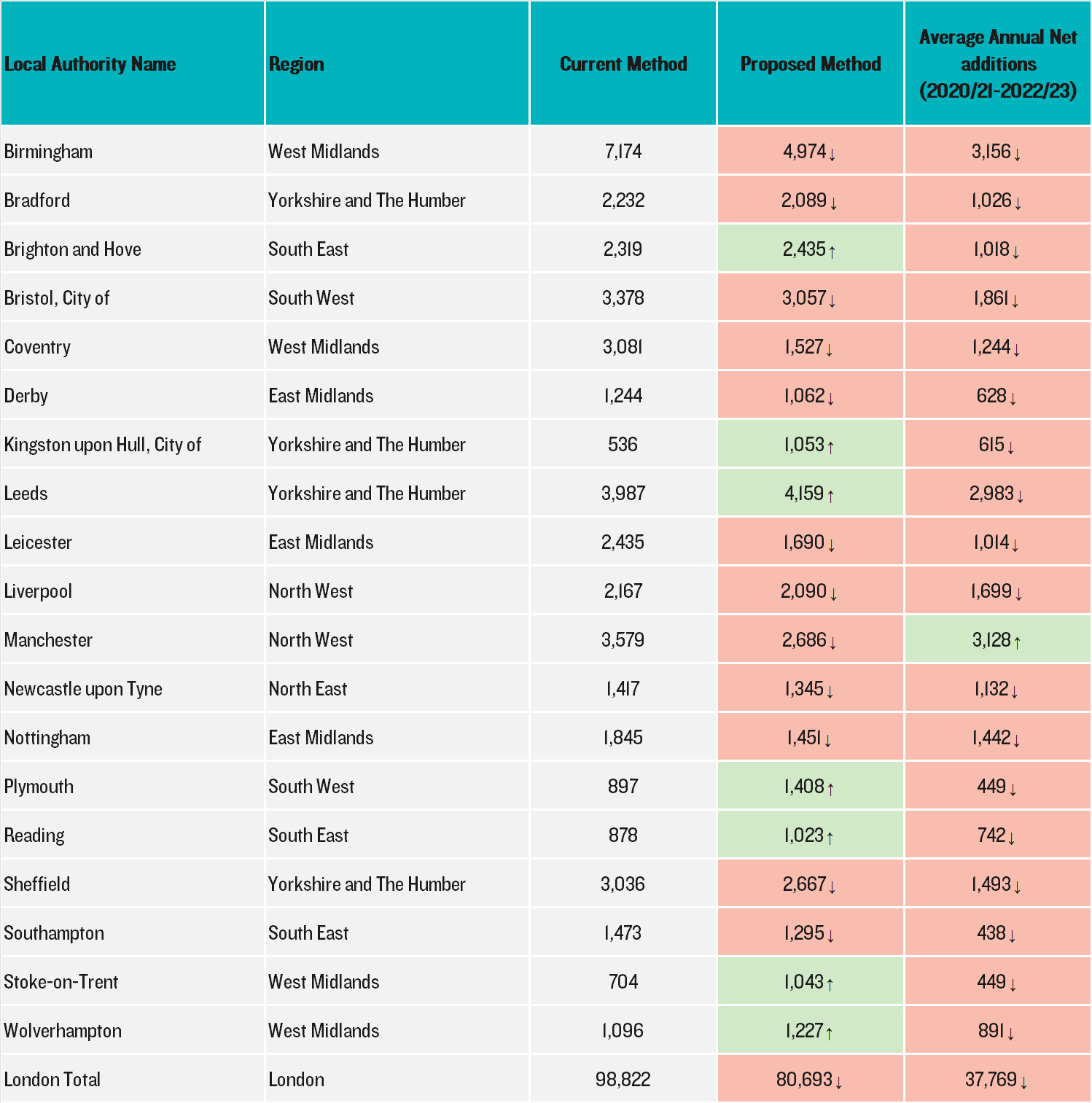

Outside the capital, compared to the current Standard Method, 90% of Authorities will see an increase in their local housing need figure. However, the pattern for urban Authorities is much different, with 13 of the largest 20 urban areas seeing an overall reduction. Of those 7 that do see an increase (shown in green), the increase is only relatively small. This can partly be explained by the new Standard Method removing the previous ‘urban uplift’ which added 35% to an areas housing need figure – the intention is to remove what was an arbitrary addition or redistribution of housing need to urban centres.

The more concerning issue for the new Government will be the fact that only 1 area, Manchester, has an average annual net addition rate higher than its new Standard Method need figure. To put this into perspective at national level, it means our biggest economic centres for growth will be expected to deliver 118,974 new homes a year, but their past performance suggests an average delivery of just 63,177.

Table 1 - Top 20 Urban Areas - Standard Method Comparison & Annual Average Dwelling Additions

So, despite urban housing requirements reducing, past performance would indicate that these new mandatory targets will still not be met, and the gap will be significant. Low levels of delivery can give rise to major social issues including affordability and homelessness, whilst housing waiting lists continue to grow and the financial burden of temporary accommodation continues to bite for many Local Authorities.

Of course, it has been a challenging time for the development industry in the wake of Brexit, Covid-19, construction cost inflation and stubborn interest rates, let alone the lack of a long term rent agreement for Housing Associations who haven’t been able to commit to development activities and are often spending greater proportions of capital on existing stock. Even allowing for a marked improvement in delivery in future years, there is still likely to be a big gap to fill, meaning both the new targets and the overarching aspiration for 1.5million homes must be a tall order. Our previous

‘Banking on brownfield’ analysis in June 2022 concluded that even if every identified site on local authority Brownfield Registers was built to its full capacity, the capacity of previously-developed land equates to 1.4million net dwellings. Even with significant government support, brownfield land can only be part of the solution to the housing crisis, and even if the majority is used in the first 5 years of this Government, where does the future supply come from?

Many of these urban areas are constrained by national protections too which will further supress delivery on their edges and outside of settlement boundaries, unless there are major alterations via Local Plans. This is often most tangible with Green Belt designations in areas like London, Greater Manchester and the Liverpool City Region, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Coventry, Leeds and Sheffield, Bristol, Newcastle, and Nottingham. In this context the NPPF retains and strengthens the Duty to Cooperate by advocating strategic planning across boundaries to achieve sustainable growth and meet housing needs. We may see the reintroduction of regional spatial planning, but in the interim urban areas are facing a mighty challenge to meet even their own (reduced) targets, yet could be asked to meet needs of surrounding areas too.

With scant availability of sites and viability being a major challenge for urban development, there will need to be a step change in local decision making and heavy levers pulled at national level to encourage more joint venture and partnership working, pump priming delivery through grant to remediate land and bring sites to market, and a big role for Homes England as the pivotal Government vehicle to drive this change

. The signs are encouraging with the recent announcement of a

new homes accelerator programme which seeks to bring forward stalled sites that already benefit from permission, and Matthew Pennycook MP (Minister of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government)

writing to Chair of Homes England, Peter Freeman, to set out his seven immediate priorities, including

“doing everything in its power to accelerate development and increase delivery in 2024/25.”In light of the impending policy changes and revised targets, it remains to be seen whether we will start to see Local Authorities stepping up to this tall order, and in that vein being a bit braver when it comes to building heights and massing to achieve higher densities on deliverable urban sites. The development industry would benefit from a top-down acknowledgment from Government that we should collectively seek to optimise the potential of urban sites when they do become available, and that tall buildings should be acceptable in principle too. This is a culture change needed in many authorities where applicants and design teams spend significant time in pre-app discussions advocating for height and density in well-connected sustainable locations, a situation that shouldn’t really be the case. Time would be better spent focussing on quality of development, place making and delivery, together with realising social value and responding to the climate emergency. Now is the time for Local Authorities of all stripes to welcome developers and housebuilders through the door, work with them to find a way for development to be brought through the planning system efficiently and effectively. If that doesn’t happen then we should expect a raft of planning appeals and potentially a number of Secretary of State recoveries, with odds of success stacked in the favour of an appellant given the political mood, assuming they have taken a responsible and well-advised approach to their planning applications.

Of wider interest to those looking to develop urban brownfield sites, the NPPF (§63) continues to advocate for Local Plan evidence bases to include a thorough assessment of rental needs. With this sector having strong institutional investment backing, and therefore ability to deliver at scale and at pace, it will be important for the urban authorities to make sure they are planning strategically for Built to Rent, Purpose Built Student Accommodation and Co-living in particular, as these tenures can make big dents in the housing need requirements, and may release traditional stock back to the market. The NPPF (§69) contains explicit support for mixed tenure sites, as are often delivered in urban areas where building mixed and balanced communities is so intrinsic to social cohesion and realising the value and opportunity arising from development and investment.

The NPPF consultation ended on 24th September, but there will be much work to do in the weeks, months and years ahead to make the most of our finite brownfield land opportunities and achieve the 1.5 million homes that Government is striving for.