The Government was elected on a manifesto ambition to deliver 1.5m homes in England in the parliament, equivalent to 300,000 homes a year for five years, a rate significantly greater than has been achieved in recent decades. But it begins this task from an inauspicious starting point, with current local plan requirements aggregating to just 230,000, the HDT benchmarks at 259,000 and recent permissions running at just 233,000 per annum (equivalent to build out at circa 175,000 once one accounts for lapse rates)

[1]. The OBR March 2024 economic and fiscal outlook

[2] forecast net completions falling to 188,000 in 2026 before rising to 220,000 in 2029, and delivering just 1,014,000 over the five year period, almost half a million short of the Government’s ambition. Some are more pessimistic than that about short term delivery.

Housing supply is not simply a function of the planning system, but there is a very strong correlation between what the planning system seeks to achieve by way of local planning targets and what is built. This is because LPAs will tend to ration the flow of permissions for housing to a level consistent with what is necessary to maintain a five-year land supply against their local requirement (witness Wiltshire Council's decision in April 2024 to reverse its previous decision to approve schemes when its land supply requirement dropped from five to four years, under the terms of para 226 of the December 2023 NPPF).

LPAs might resist proposals for housing in their area (often successfully) if they are not deemed necessary in order for an area to meet its local target, because the benefits of extra housing supply might be perceived as less and thus outweighed by harms, when it comes to applying the ‘tilted balance’. For a number of other, more land-constrained areas, delivery is in effect restricted to the capacity of that area – even when the target is set at a higher level, with London being a good example. This is why a national target, say of 300,000 homes a year, will not be met if this does not translate to deliverable local targets.

The draft NPPF and proposed changes to the Standard Method for local housing need – both out for consultation – seek to boost housing delivery by, inter alia:

-

Changing the formula for local housing so that in aggregate, areas need to plan with the aim of achieving 370,000 homes a year, nationally;

- Requiring LPAs to maintain a five year land supply, without which the presumption in favour of sustainable development applies;

- Changing Green Belt policy so that:

- areas must review Green Belt in their Local Plans and, where justified, release land in order to meet housing need; and also

- ‘provide opportunities for so-called ‘Grey Belt’ land to be developed ahead of a local plan by way of planning application;

- Strengthening the strategic planning approach such that one might expect a greater amount of unmet need from constrained areas to be provided for in neighbouring areas; and

- Requiring that proposals for housing on previously developed land should be regarded as acceptable in principle.

In general terms, these measures place strong upward pressure on the planning system’s approach to supporting the delivery of new homes. However, the question is whether they go far enough in light of:

-

The inevitable lag period in which any planning decisions in support of new homes (in the form of allocations or permissions) would be unlikely to achieve real world housing completions for a period of at least 2-3 years

[3], meaning that in the short term, delivery is largely a function of the inherited planning pipeline and economic conditions; and

- The Government’s proposals for transitional arrangements on local plans in which:

- areas with adopted Local Plans at the time of the adoption of the NPPF would continue to apply their pre-NPPF housing requirements for five year land supply purposes for five years from the date the plan was adopted; and

- areas that submit a Local Plan for examination within a month of the publication of the NPPF will see whatever housing target emerges in that plan once adopted as the basis for its housing trajectory and five year land supply for up to five years, depending on when a replacement plan is adopted, with the pace of the new plan partly dependent on whether or not the emerging plan is within 200 homes of the proposed new Standard Method.

A number of LPAs stand to have existing/emerging Local Plans fall within the proposed terms of the transitional arrangements, and this means that their local housing requirement will be lower than it might otherwise have been had they prepared their plan under the terms of the proposed new NPPF

[4]. Although those falling more than 200 homes below the proposed Standard Method would be expected to prepare a plan under the new plan making system at the earliest opportunity, this is unlikely to begin

at least until 2026 and will not lead to adoption of that plan before 2029, even based on a 30+4 month timescale.

What does the combination of the above mean in terms of the practical local plan targets that will likely apply for five-year land supply purposes over the next ten years and what might this in turn mean for net housing additions over that period?

To explore this, in work prepared pursuant to an instruction from the Home Builders Federation (HBF) and the Land, Planning and Development Federation (LPDF), we have generated a model to explore the potential trajectory of planned housing targets (in terms of the annual rate that would apply for five year land supply purposes), and housing delivery associated with that. We explain the broad approach before presenting the results, followed by some recommendations.

Approach

As with any modelled approach, it is necessarily a function of the assumptions applied about what might happen in the future and thus it illustrates a concept rather than representing a precise forecast. The implications would depend on what individual LPAs might do and precise duty to cooperate and other discussions. We have adopted a proportionate but consistent approach at a national level, applied to every England LPA area based on its context, local plan status, past housing delivery, and standard method housing number. The approach is as follows:

- We have categorised every LPA as being either:

- ‘Constrained’ where housing delivery is largely a function of the capacity of the area, based on past rates of net housing completions, but with an increase of 13% based on the impact of the proposed change to para 122 (c) on publication of the new NPPF and a further increase of 13% on adoption of a new Local Plan. This uplift is based on the analysis in the January 2024 London Plan Review of the impact of the 2012 NPPF presumption in favour of sustainable development. In general terms, our assessment assumes a constrained LPA has a ‘cap’ on its realistic ability to meet the new standard method in the current operating environment and thus will be a generator of ‘unmet’ need.

- ‘Receiver’ authorities where in principle they have the ability to meet their Standard Method housing need and accommodate unmet need from ‘constrained’ LPAs.

- All LPAs have been grouped into sub-regions that are a best fit for existing or possible future sub-regional strategic planning areas.

- We have identified the Local Plan housing requirement for each LPA where this is from a Strategic Policy in a Local Plan adopted within the past five years. We have assumed this number applies for five year land supply purposes until it is five years old, whereupon the proposed new Standard Method figure applies[5].

- We have identified the LPAs that have, or are identified as being likely to, submit a Local Plan for Examination before January 2025 (based on the assumption that the NPPF is adopted December 2024) and are thus likely to benefit from the transitional arrangements. We have assumed that Local Plans are found sound and adopted with the same housing requirement as when the plan was submitted, although clearly this might change depending on the process of the Examination.

- We have identified when a new Local Plan would be put in place for every ‘receiver’ area and then applied a housing target for that plan that:

- Meets its own Local Housing Need (based on the new standard method);

- Makes a contribution to meeting unmet need from ‘constrained’ LPAs within its sub-regional strategic planning area. We have taken assumed that ‘receiver’ LPAs would meet a proportion of the unmet need for the sub-regional strategic planning area equivalent to their contribution to the overall Standard Method housing need for the area. By way of an example, Shropshire’s Standard Method housing need of 2,059 makes up 20% of the total target for the Western Midlands (Stoke, Stafford, Shropshire & Worcestershire) sub-regional strategic planning area. Therefore, Shropshire is allocated a further 20% of the 750 dpa unmet need for Western Midlands (equivalent to 154 dpa), giving a total housing target of 2,213 dpa. In most strategic planning areas, unmet need is mopped up, but some areas (with fewer 'receivers') fall short.

-

For assessing actual forecast housing delivery, we have:

- Assumed that the OBR March 2024 Economic and Fiscal Outlook assumption applies for the period 2024-2027 on the basis that what is to be built in those areas will largely be a function of what already has/or will shortly receive a permission and the underlying economic circumstances that apply. Some might say this forecast is itself optimistic so it therefore in our view captures the possible benefits of short term Government measures, for example on funding, social housing, or tackling problems like water or nutrient neutrality.

- For the period from 2028 onwards, we link the delivery of homes by i) for 'constrained' LPAs, to their past rate of delivery plus the 13% uplift to account for para 122 (c) and a further increase of 13% on adoption of a new Local Plan that we assume brings forward additional sites/capacity; and ii) for 'receiver' LPAs, to their planned housing target from the period three years prior, with an assumption that delivery runs at an average of 92% of the target, based on how current delivery relates to the Housing Delivery Test benchmarks.

-

We then look at what this means for total planned targets and for housing delivery for the first five-year period of the new NPPF (assuming adoption from December 2024) and for the second five year period (years 6-10). We then identify the difference between the planned target based on with the transition period and without it.

Analysis

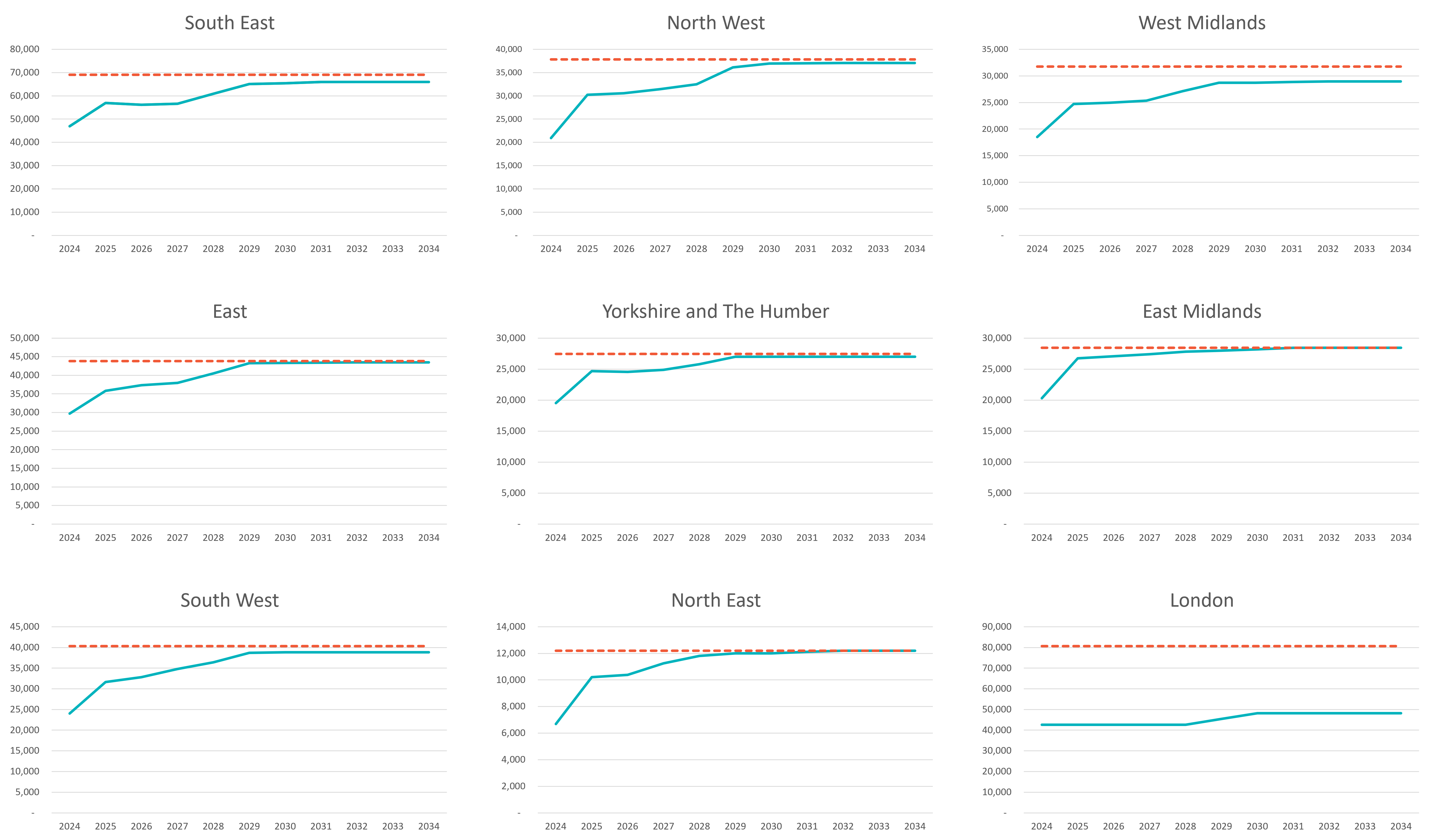

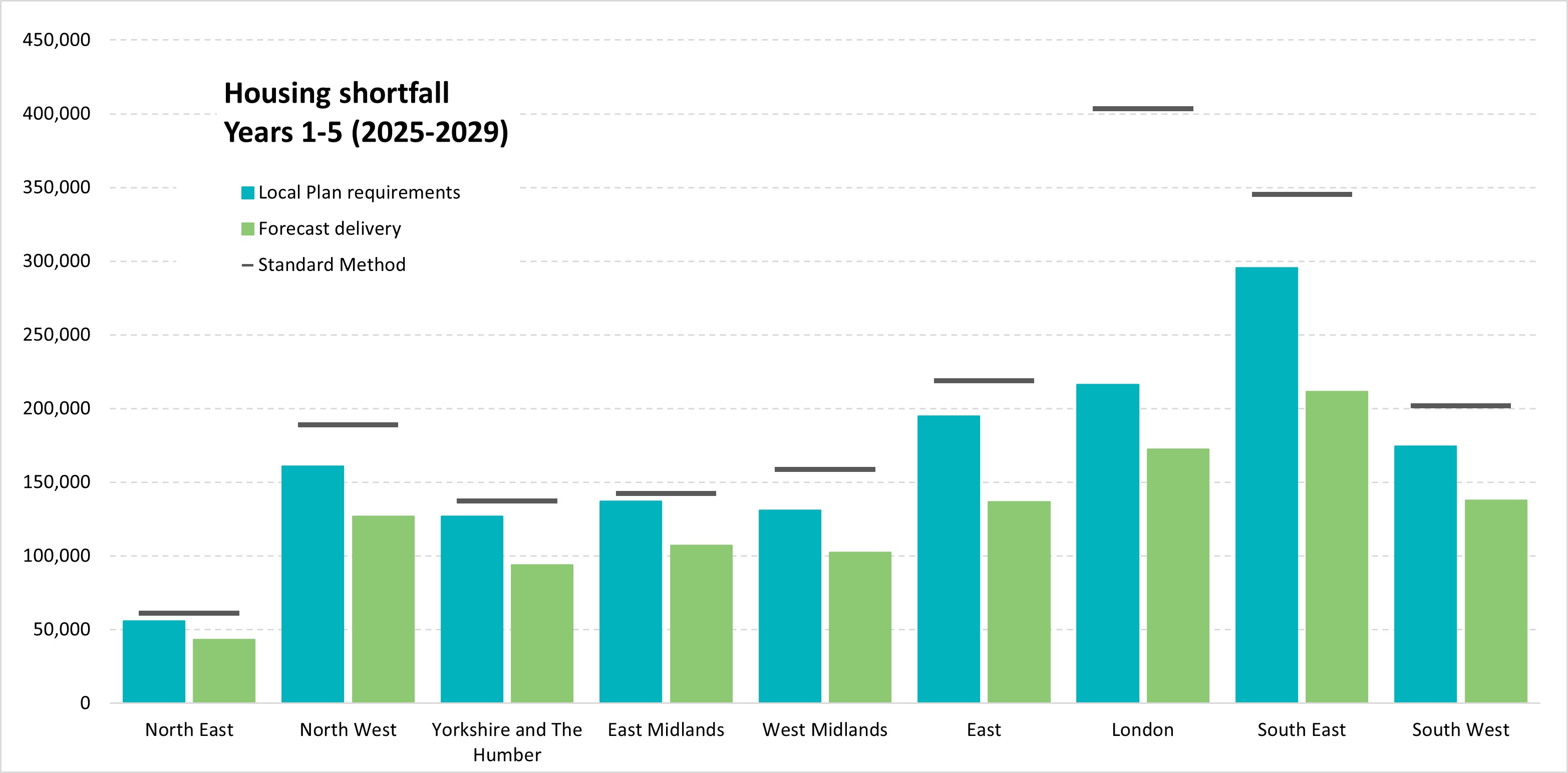

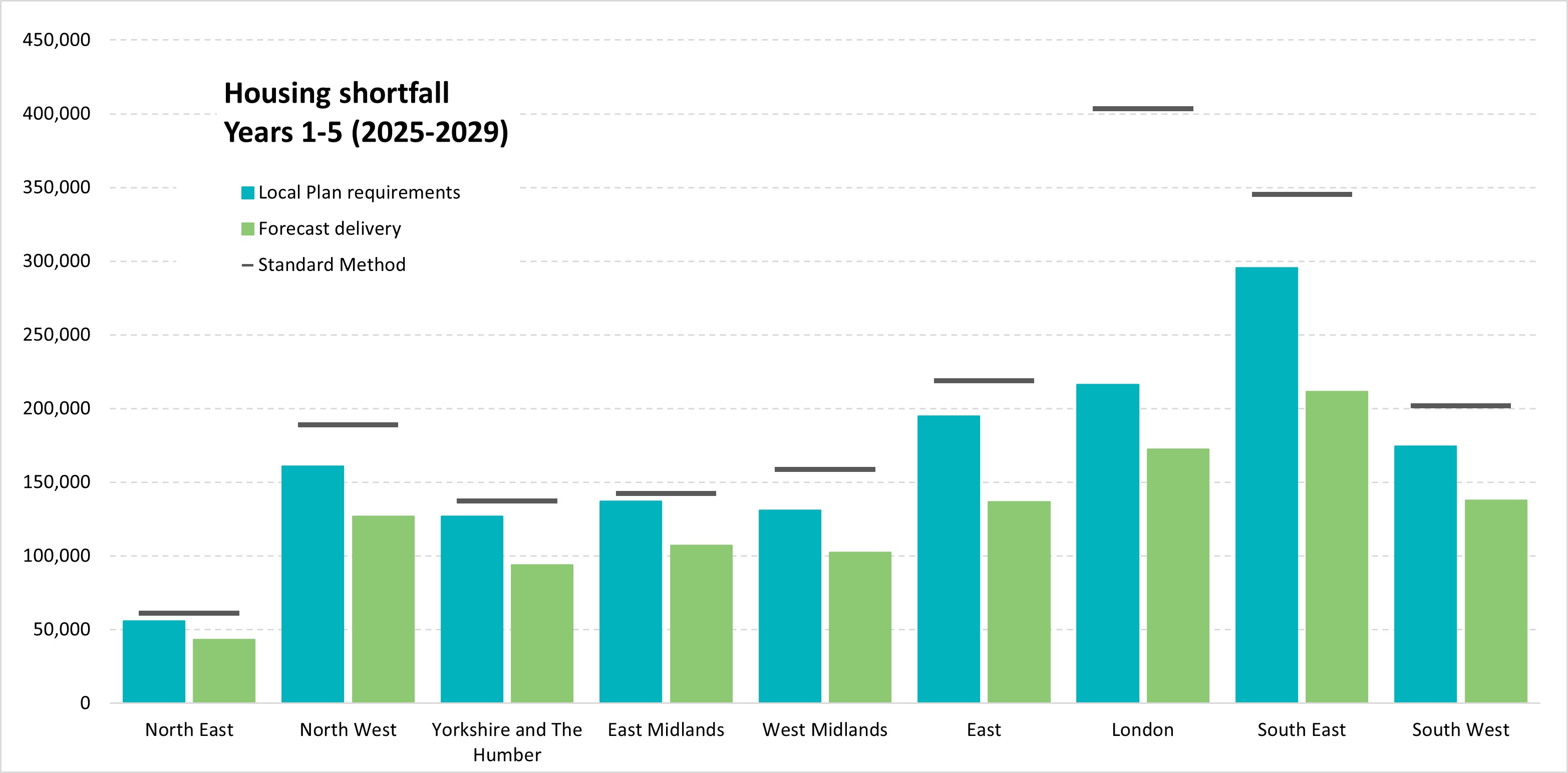

The individual regional trajectories for progress towards the new Standard Method for local housing need by region are illustrated in Figure 1. In Figure 2, the totals are presented across the first five years of the new NPPF, alongside Local Plan housing targets and a forecast of housing delivery.

Whilst a number of LPAs would immediately take on the new Standard Method figures for decision taking (through out-of-date plans and a lack of five-year housing land supply), a notable proportion would continue to operate under lower housing need figures. This would include the circa 30% of LPAs with a Local Plan adopted within the past five years alongside around 50 LPAs that could expect to benefit from the transitional arrangements set out at Annex 1 of the draft NPPF. The new standard method and its 370,000 annual target therefore remains an elusive prospect, particularly over the first five years of the new NPPF where both Local Plan requirements and forecast housing delivery cumulatively fall short of the national annual target by 370,000 and 730,000, respectively over the five year period to 2029.

Figure 1 - Regional Housing Target Trajectories

This is particularly stark in London, which history shows as being constrained and persistently delivering around 30-40,000 homes a year, and for various reasons (such as those identified in the London Plan Review

[6]) is likely to continue under-shooting its housing delivery for the foreseeable future, resulting in a cumulative Local Plan target of just over 200,000 over the first five years, around half of the 400,000 target under the Standard Method. By contrast, in the context of the applied methodology, the North East does not have any constrained LPAs, and Yorkshire has just two. As a consequence, these regions are considered to have a far greater immediate capacity to meet the new standard method, albeit this will not be achieved immediately as up-to-date Local Plans and transitional arrangements lock-in ‘old-style’ housing need figures.

Given the inherent lag between the adoption of a Local Plan housing target, preparation, submission and determination of a planning application, discharge of all relevant conditions and reserved matters and construction, it is to be expected that the delivery of new housing over years 1-5 is then forecast to fall short of housing need identified through the Standard Method, providing just over 1,130,000 new homes between 2025 and 2029.

This equates to 60% of the standard method and averages out at 226,000 dwellings per annum. This is moderately above the 'business as usual' scenario we identify from the OBR’s March 2024 forecast (albeit to a different build-out profile) and flows from the uplift taking effect in the final two years of the period.

Figure 2 - Housing shortfall (2025-2029)

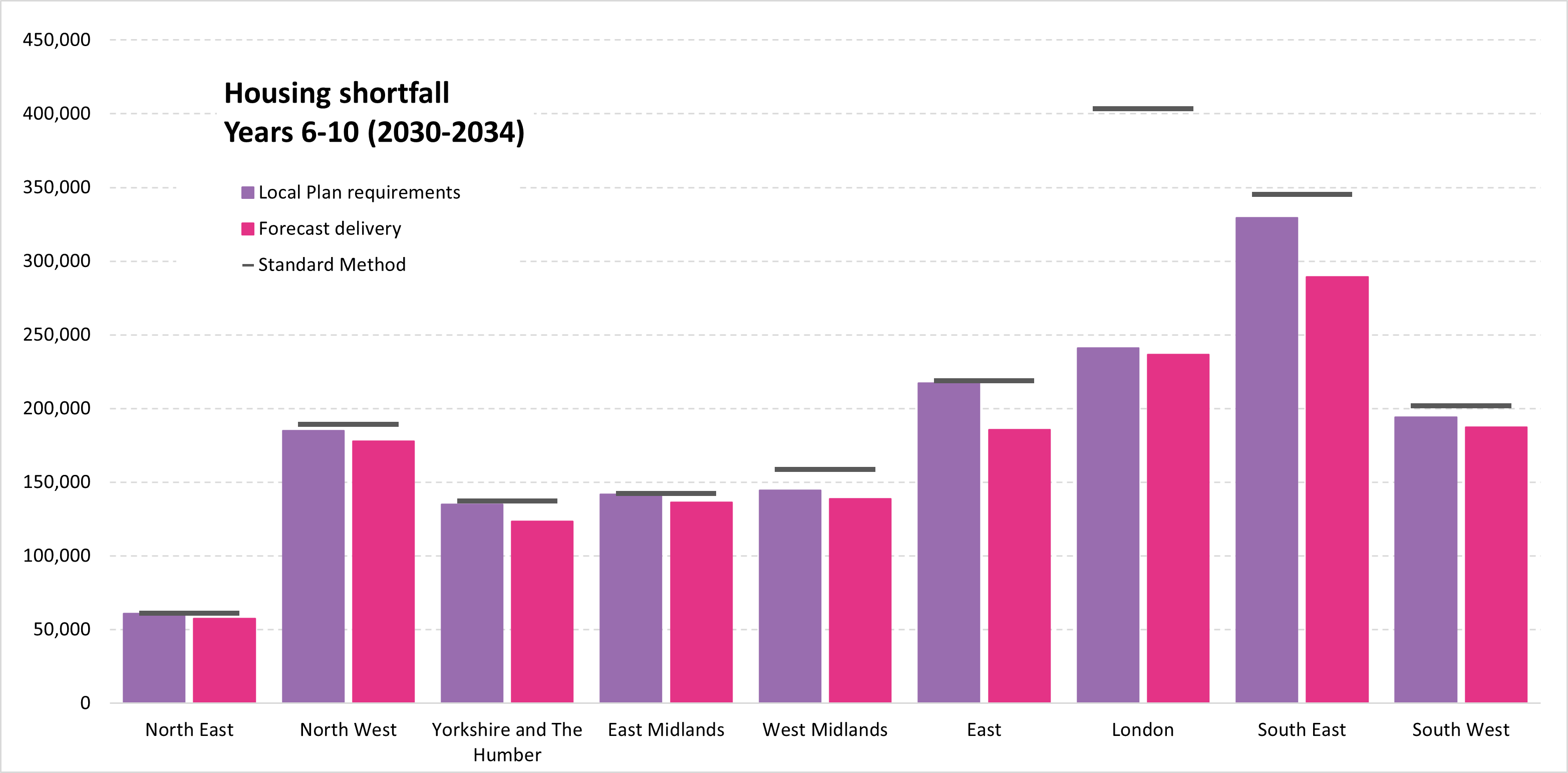

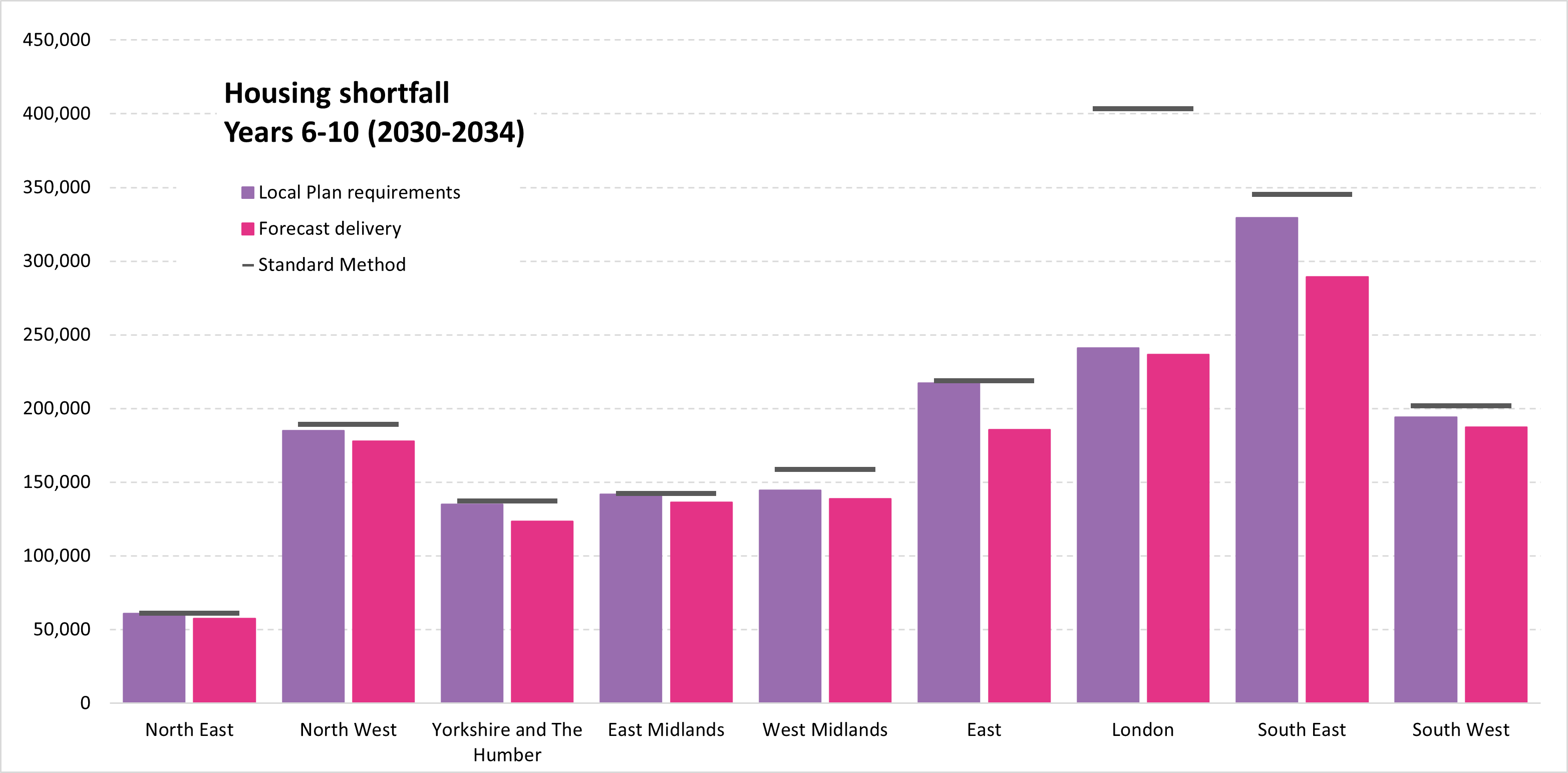

Figure 3 - Housing shortfall (2029-2034)

A more positive picture is seen across the second five years of the new NPPF (see Figure 3). With the exception of London and its assumed ongoing constraints, all other regions are estimated to more or less reach the housing targets set by the Standard Method.

These higher housing targets result in a corresponding uplift in housing delivery which is forecast to rise to 1.6m between 2030 and 2034: a notable improvement on past levels, but still 20% short of housing need under the proposed Standard Method.

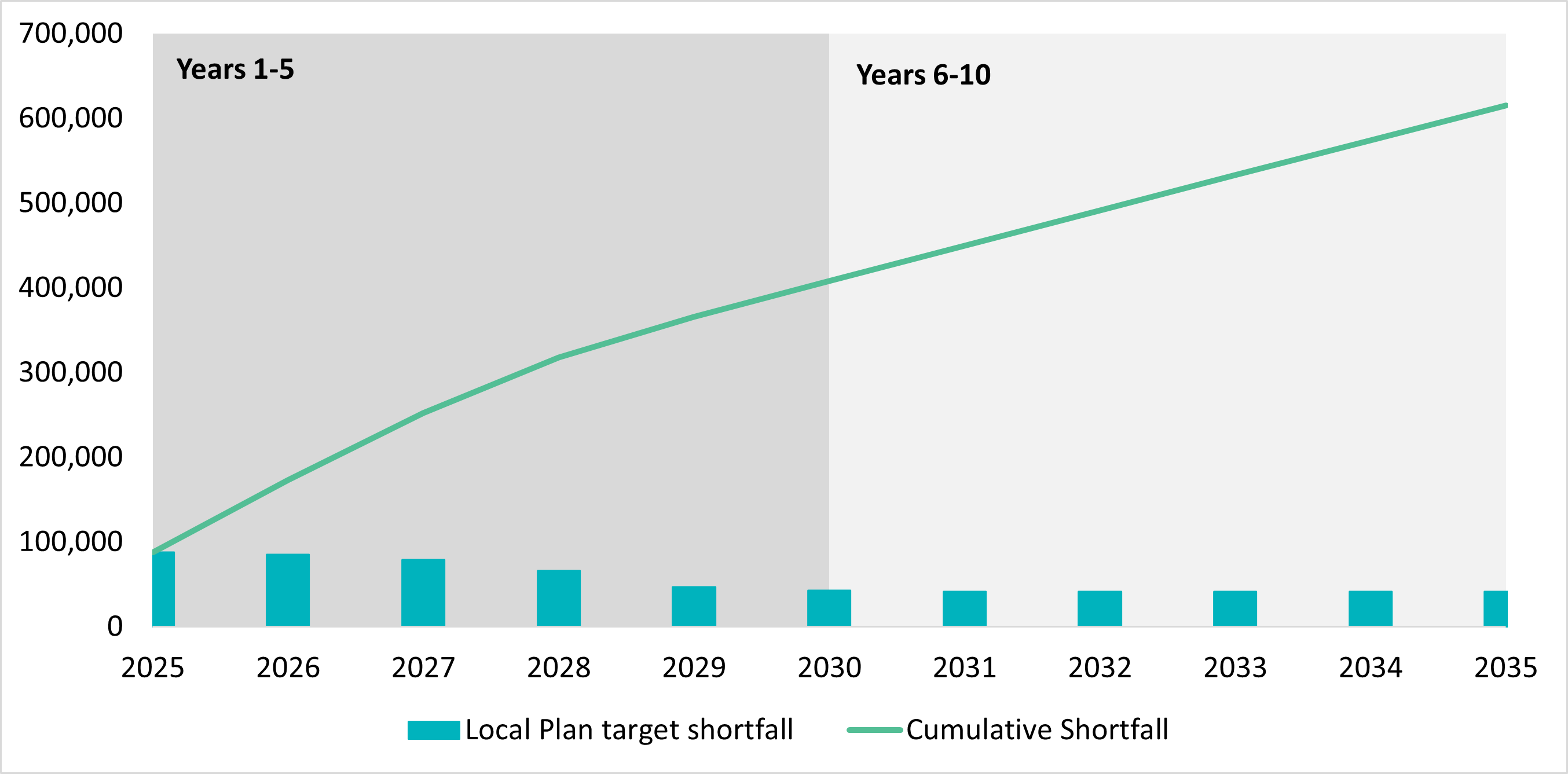

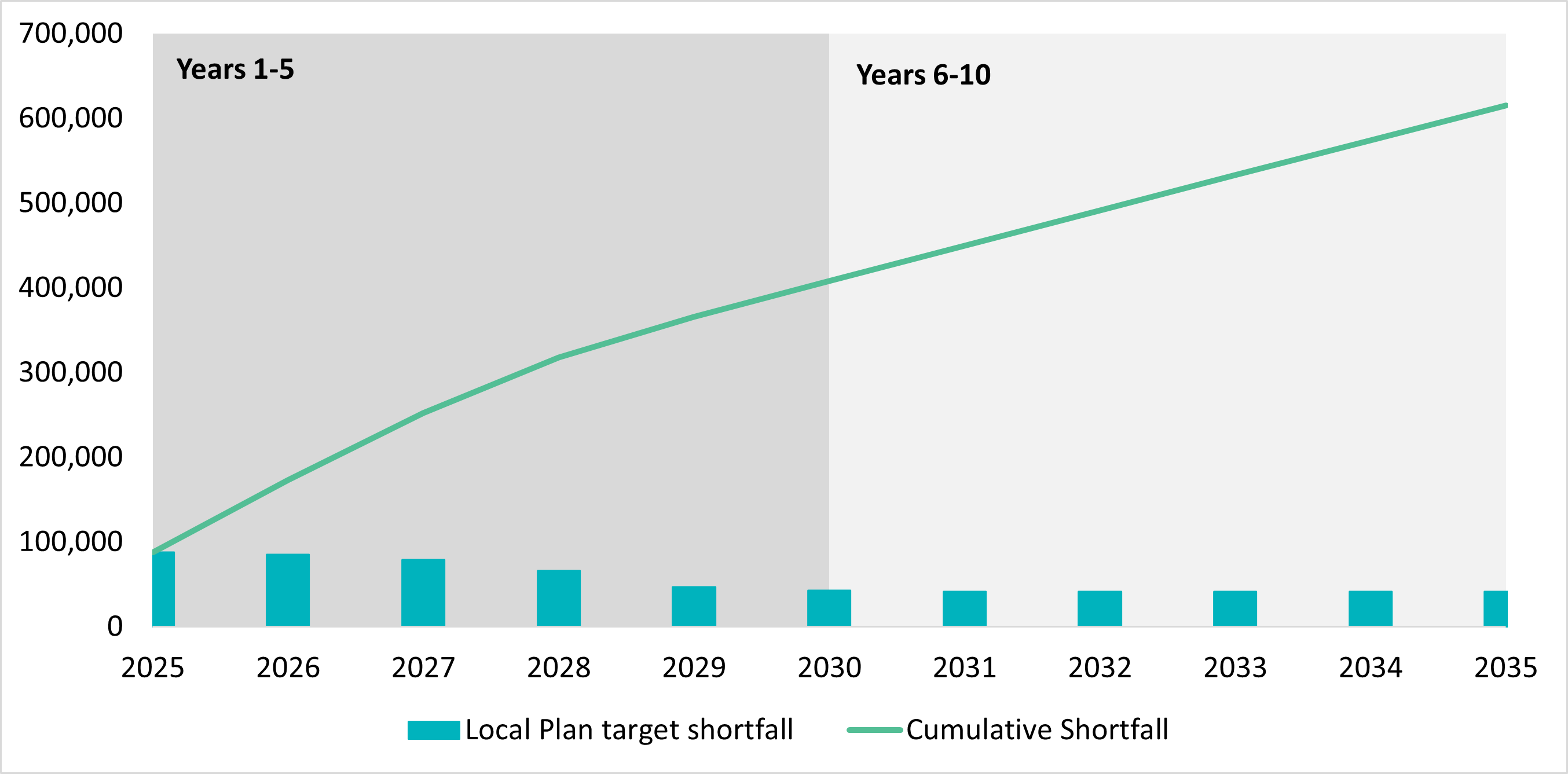

The implications of LPAs continuing to plan for less than their local housing need identified through the Standard Method is set out at Figure 4, which shows a cumulative shortfall of 370,000 homes by 2029 between Local Plan targets and the Standard Method housing need, growing to 615,000 by 2034.

Figure 4 - Local Plan target shortfall against Standard Method

Whilst a proportion of the shortfall is partly a result of LPAs with existing up-to-date Local Plans, there are also a significant number of LPAs where submission of a plan under the current NPPF with the proposed transitional arrangements would delay the preparation and adoption of a new plan that aims to address the new housing need figures, including unmet need

[7].

The transition 'opportunity' has led to a rush of LPAs announcing early consultations and condensed timeframes in an apparent effort to defer the increase in housing numbers. A list of LPAs that have submitted or published an emerging Local Plan that would benefit from the transitional arrangements or have announced that they intend to submit or publish their Local Plan prior to the implementation of the new NPPF is provided at Appendix 1.

In light of the Minister of State’s instruction

[8] that PINS should no longer follow a doctrine of ‘pragmatism’ (whereby Local Plans at Examination would be prolonged - sometimes interminably - to allow for updates and additional evidence, rather than being found unsound), it is possible that a number of these emerging Local Plans may be withdrawn or found unsound. We have nonetheless assumed for our assessment that the LPAs have submitted a plan they consider to be sound and that they will progress. This is a prudent assumption for our assessment, given that progressing a plan that is ultimately not adopted will still delay the practical impact of the new Standard Method housing need in terms of realistic applications in the short term.

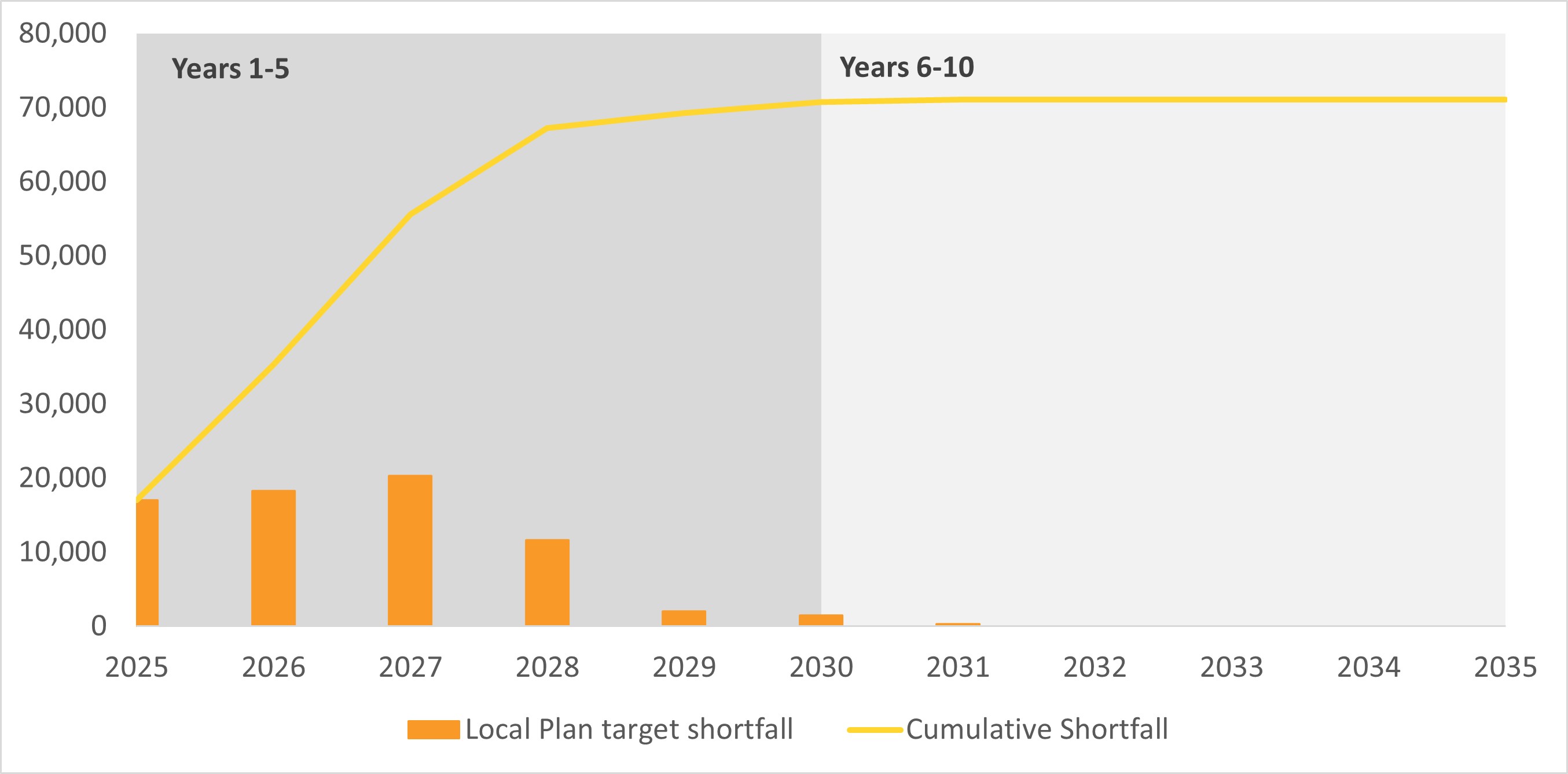

Compared to a scenario without any transitional arrangements (i.e. if the NPPF and Standard Method applied immediately), the proposals in the draft NPPF would directly result in a shortfall of over 70,000 homes being planned for, with the majority of this undersupply falling within the first five years of the new NPPF. There is a lag effect in terms of build out from submission of applications, but within the first five years to end of 2029, this would lead to around 35,000 fewer homes being built in the final two years (equivalent to 15-20,000 per year in years four and five) than if the transitional arrangements were removed.

Notably, this shortfall is not just a result of individual LPAs progressing Local Plans that fall short of their own housing need as identified by the Standard Method. Significantly, a number of ‘receiver’ LPAs are those that would likely need to address not only their own housing needs but also increased amounts of unmet housing need from constrained LPAs in their sub-region through the duty to cooperate (or future strategic planning mechanisms). By progressing now under the transition arrangements, they will 'lock-in' to their lower housing targets and extend the period before that unmet need is addressed.

Even if these submitted plans are subsequently found unsound or have to be withdrawn, or the LPA is required to begin progressing a new Local Plan under the new plan making system, the transitional arrangements would delay the adoption of a new plan until at least 2029, compounding the identified shortfall. This is in the context that we do not yet know how the new plan making arrangements will apply in practice and what "at the earliest opportunity" in para 227 means in practice.

Figure 5 - Local Plan target shortfall under Transitional Arrangements

Summary and conclusions

The proposed NPPF in combination with changes to the Standard Method puts in place a positive platform for boosting annual housing delivery to 300,000 net additions and beyond. However, the analysis shows that the number of homes that will realistically be delivered will be subdued for at least the next few years. The causes lie in multiple factors, including the difficult planning legacy of the period from 2020 leading up to the December 2023 NPPF, ongoing issues around nutrient and water neutrality, Registered Provider capacity for affordable homes, and the challenging economic circumstances impacting on demand.

This places a heavy burden on the later years of the five-year period commencing 2025 to boost housing supply to address the inevitable backlog that arises (from the Government’s goal of 1.5m homes within the Parliament. But the lead-in times mean that planning for that post-2028 boost needs to happen immediately. Figure 6 below presents a forecast of likely targets and housing delivery based on the current NPPF and its transitional arrangements, applied based on the status of Local Plans.

Figure 6 - Overview of forecast Local Plan targets against Standard Method and Housing Delivery

Our modelled assessment, based on a set of assumptions applied to every LPA, identifies that:

- Constraints to supply in some LPAs, and especially in London, means that the long term ‘run-rate’ for planned housing targets and its delivery could sensibly reach over 300,000 per annum in the medium term. This is to large extent achieved by virtue of boosts to delivery in areas current constrained by Green Belt. In the context of the past few decades, and the circumstances as they are today, this would still be a positive achievement.

- However, the transitional arrangements proposed – in which five year land supply and application of the tilted balance in many areas will be determined by current adopted or emerging local plans – act against the Government’s stated objective and will limit the immediate boost in flow of permissions that is necessary to significantly increase delivery within years 4-5.

- Compared to a situation where there are no transitional arrangements in the NPPF, and the new Standard Method applies immediately in all LPAs, the impact of the transition equates to 70,000 fewer homes being planned for in years 1-5. The transitional arrangements have a ‘double whammy’ impact:

-

- Where an LPA has a plan set at lower than the new Standard Method, it bakes in that lower target for five-year land supply purposes until that plan is replaced by a new NPPF-compliant plan, and for those areas that have or will submit a Local Plan before the new NPPF applies, that is unlikely before 2029, if at all.

- Where the LPA is a ‘receiver’ in an area likely to face taking on-unmet need from constrained LPAs, the transitional arrangements are likely to result in the unmet need remaining unaddressed ahead of the new post-NPPF local plan coming into play from 2029 or later. The 200-home threshold for emerging Local Plans ignores the presence of unmet need within a local area, meaning that some areas pressing ahead with plans close to their own standard method, but without engaging with higher levels of unmet need in their sub-region, will not need to address it before new Strategic Plans might emerge, which even if all runs smoothly is likely towards the end of this decade in areas outside the existing Mayoral/Combined Authorities.

If further LPAs bring forward Local Plans and/or the publication of the NPPF extends into 2025 (unlikely, but one never knows), the effect of the transition will worsen.

Recommendations

In broad terms, we do not see a strong case for the proposed transitional arrangements if the Government’s aim is to genuinely boost housing supply towards the 1.5m home goal within years 1-5. In some cases, LPAs that would benefit from the transitional arrangements are only in that position because they are running some years behind schedule (having delayed their plans following the December 2022 NPPF consultation) and/or have suddenly accelerated production in the immediate aftermath of seeing the proposed NPPF and Standard Method that would increase the housing need pressure on their area.

There might be said to be a 'moral hazard' in protecting those LPAs from the consequences of their delay in these circumstances. Equally, one needs to be careful not to ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’ in that some of the local plans (however late they are) will be allocating new sites to support housing delivery, and particularly for larger-scale allocations, one might not otherwise see those proposals emerge through applications running ahead of the local plan

[9].

There appear to be three options:

- Maintain the current proposed transitional arrangements: based on our assessment, this would appear likely to undermine the Government’s ambitions to boost supply. But were transitional arrangements kept, it would still be necessary to give a cut-off period for a plan submitted under the transitional arrangements to be adopted, otherwise it risks an LPA ‘gaming’ the system to draw out the period of examination and adoption to extend the period in which lower housing requirements apply. The Government may wish to consider alternative thresholds based on a percentage of total housing in an LPA rather than a flat-rate of 200 dpa, which can equate to a significant proportion of overall need for smaller LPAs. Overall, though, we consider sticking with the draft proposals is least consistent with the Government's stated objective.

- Remove all transitional arrangements: this would mean that immediately on adoption of the new NPPF:

- Any plan that was at Examination ahead of adoption or receipt of the Inspector’s Report would need to be examined against the new NPPF and Standard Method. Some Local Plans might well be in a position to be modified to accommodate higher housing targets (their own or neighbours), but others might find themselves having to be withdrawn because the proposed changes cannot be addressed within six months (pursuant to the Minister of State’s instruction to PINS on 'pragmatism' referred to above). This might lead to otherwise welcome housing allocations – including in areas of Green Belt – falling away. This latter risk could be mitigated by providing in the NPPF for draft allocations in emerging Local Plans that have been through Reg 19 to carry some weight in favour of development being granted permission were planning applications for those sites submitted ahead of a fresh local plan being prepared; and

- Irrespective of when an existing or emerging Local Plan was adopted, the five-year housing land supply for an LPA should be immediately based on the new Standard Method figure, not the adopted requirement figure, until a new NPPF-compliant Local Plan was in place;

- Hybrid transitional arrangements: this would provide for emerging Local Plans to proceed as submitted in order that emerging housing allocations and policies are given the chance to proceed in a sound plan, but any existing or emerging strategic plan examined before the new NPPF would not set the housing requirement for five year land supply purposes unless it was higher than the new figure for that LPA in the new Standard Method and would in any event be subject to immediate review.

None of these would directly address the problem that, ahead of a strategic plan or the duty to cooperate applying to new Local Plans (which are unlikely to be in place at least before 2029), the unmet housing need arising from the Standard Method (and the fact some areas face constraints) will likely remain unaddressed (falling between the cracks). The Government could seek to resolve this to some extent in the short term by a further change:

- Within twelve months, use a Statement of Ministerial Policy to identify a series of strategic planning areas (based on Mayoral/Combined Authorities and other logical geographies, including emerging devolution deals) where the Government considers unmet development need is likely to be significant and either:

- prescribe quickly within those areas a preliminary estimate of how unmet need should be distributed for five-year land supply purposes as an adjustment to the Standard Method, pending a formal distribution through the eventual strategic plan; or

- identify that within the strategic planning area, it should be assumed that there is no five-year land supply in any LPA ahead of a strategic plan setting the distribution.

Appendix 1 LPAs falling under Transitional Arrangements

Footnotes

[1] See analysis in this blog here

[2] The OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook is here

[3] See the benchmarks in Start to Finish

[4] See the examples as reported in Planning Resource here and here (£)

[5] We have not modelled the individual backlog position on 5YHLS based on adopted Local Plans and assume the annual requirement applies for each year.

[6] The London Plan Review is available here

[7] Which, under the new NPPF, all falls to be addressed via the duty to cooperate, compared to the current NPPF where the 35% urban uplift does not need to be addressed in neighbouring LPAs if it cannot be met within the urban area.

[8] See letter to Chief Executive of the Planning Inspectorate here

[9] That is not the case with all plans. A number claim to be able to already demonstrate a five year land supply even without their Local Plan. Their new Local Plans are therefore more focused on addressing need for years 6-10 and 11-15 of their period.