This year, we asked our annual town planning interns in the Edinburgh office to consider what Scotland’s new towns could teach us about 20-minute neighbourhoods and planning for the future. This blog reviews Livingston and

Katherine Bannister reviewed Glenrothes.

During the summer, as part of Lichfields internship programme, I worked in Lichfields’ Edinburgh office. In particular, I looked at Livingston New Town, specifically examining how the 20-minute neighbourhoods built within it have fared 60 years on, how successful they have been, and what lessons can be learnt for future planning.

Livingston’s development

Livingston was developed in the 1960s between Glasgow and Edinburgh to connect the West to the Forth Basin. Originally the area was used for shale mining. Livingston Village existed at this time and the New Town adopted its name. Livingston’s connection to the industrial sector continued with the proposed new town planned to operate as an ‘overspill town’, which would offer housing to people from Glasgow and work within new industrial sectors being setup within Livingston.

Livingston New Town was to be a collection of new neighbourhoods. The first of these was Craigshill, built 1966 in the centre of the eighty miles squared border initially envisaged for Livingston. In theory Craigshill is the perfect 20-minute neighbourhood, with a radial distance of 800m (10-minute walk, 20-minutes there and back) from the Craigshill Shopping Mall containing most of the area’s residential properties. This Mall still provides a good level of local facilities and services. It has a health centre, dentist, pharmacy, pub, food shops, cafes, takeaways, barbers/hairdressers, pet shop, betting shop and library. Furthermore, there are schools and a leisure centre within/on the edge of Craigshill. There are local employment opportunities within walking distance from the residential areas. This combined with the proximity to St John’s Hospital and Almondvale Shopping Centre (both approximately one mile away), and the industrial units to the north of the neighbourhood should mean that employment within Craigshill is reliable and economically the residents well provided for.

The 20-minute neighbourhood concept is expected to support health and wellbeing to create a higher standard of living in condensed communities. Yet Craigshill as a community is struggling, this is not the case for all of Livingston’s neighbourhoods. Some like Craigshill are facing higher rates of deprivation than standard, against newer more affluent villages which on average do not face the same issues regarding health, income, or employment.

Craigshill can tick all the boxes in terms of facilities and services and employment within an easy walk or cycle but social economic challenges have been prevalent in recent years and parts of Craigshill now ranks in the bottom five percentile for deprivation within the entirety of Scotland. Much of the rest of the area falls into the bottom 20%. Generally, health is below expected standards. In Craigshill, on average, life expectancy for women living in the area was 10 years lower than the rest of West Lothian, and 11 years less for men.

Looking at data from the 2022 Scottish Census, it was revealed that roughly 51% of residents travelled to their workplace through use of a private car with 11% using public transport. It is worth noting that these figures will have been influenced by the Covid-19 pandemic, 28% reported that they were working from home at that time. Given the design of Livingston was created to emphasise cycle use and walking with dedicated lanes to the centre which contains multiple employers one mile away from Craighall, it would make sense for people to work within Livingston. In 2011 only 33% of employed people above working age travelled more than 5km to work (so outside of Livingston), and in 2022 this was 26%. This represents a good level of containment in the town although the decrease in 2022 could be attributed to the higher number of people working from home at that time. In 2022 there was a 17% increase in working from home.

Overall, it is my belief that Craigshill does offer a lot of the expected prospects that would be provided within a 20-minute neighbourhood. Everything was in place for Craigshill to succeed, its layout, its proximity to several different employers, and at time of development modern housing. However, social and economic problems regarding health, economic inactivity, and anti-social behaviour have caused issues which have drawn the area away from the expectations of the 20-minute neighbourhood. It would be beneficial for other 20-minute neighbourhood plans to consider these factors and the needs of the individuals living there, or risk them facing the same problems in the future.

So will the next generation of 20-minute neighbourhoods in West Lothian fare better?

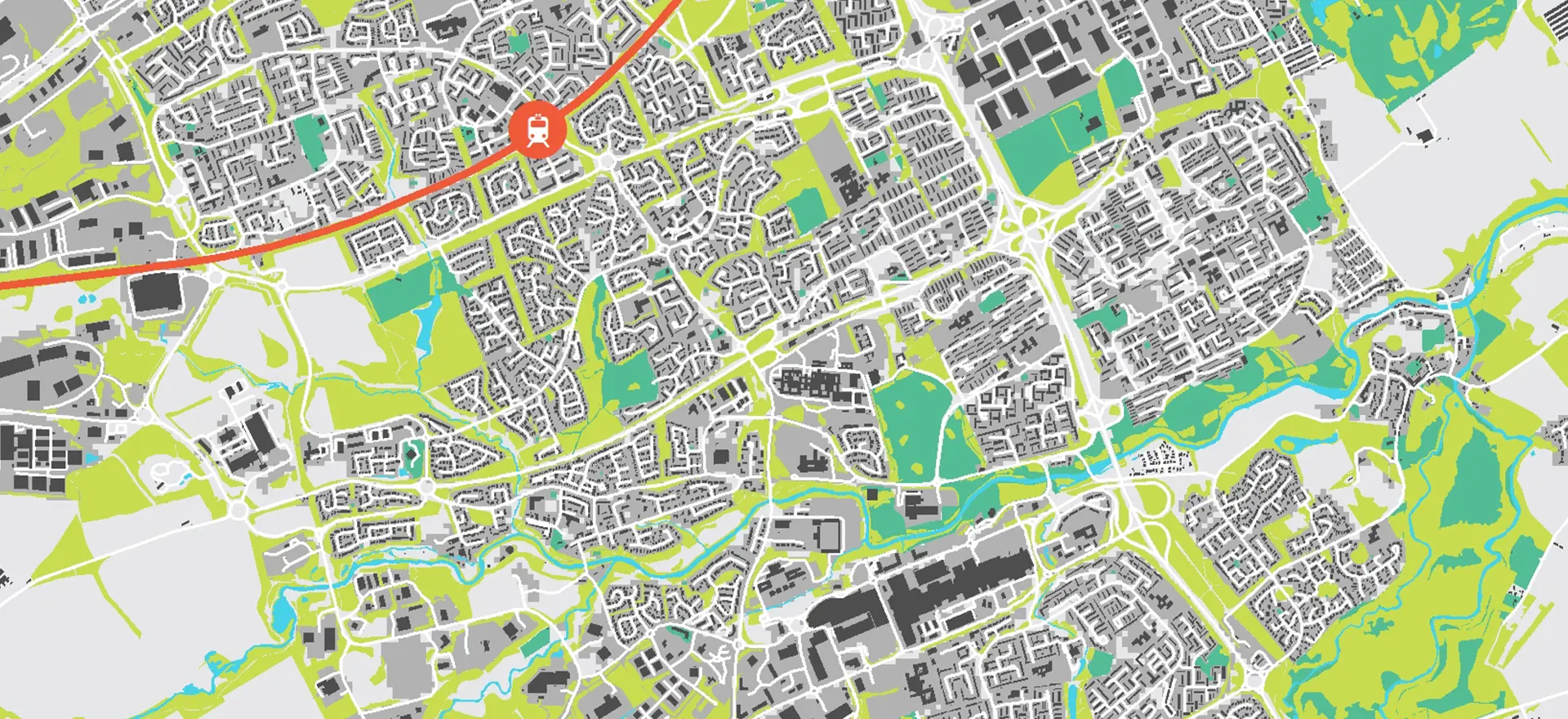

West of Livingston’s border a new 20-minute neighbourhood The Gavieside Village is undergoing planning, so how does this compare and what lessons can be learned? The village aims to be an ecologically sustainable alternative to city living, while still offering all necessary amenities. A stringent focus has been put on promoting walkability in the area, with houses stemming from a central hub and no through roads being made available from the main road linking the village to Livingston. Both Craigshill and Gavieside will have a similar number of homes although unlike Craigshill the majority of the homes at Gavieside will be for owner-occupiers, 25% will be affordable homes. In Craigshill at the time of the last Census, approximately 50% of the homes were socially rented. In the planning of the new community precautions are being taken to ensure that Gavieside offers employment opportunities across eight hectares of dedicated space, and that direct links are provided to nearby West Calder train station and new bus links are created. With the centre at Craigshill there is also dedicated employment space and there is significant employment to the north, but as stated above the neighbourhood suffers from deprivation. It will be interesting to see if the employment provided at Gavieside meets the needs of the new community and whether or not the opportunities provided are taken up by the residents of the new village.

All the elements are in place at Gavieside as they were at Craigshill and it will be interesting to revisit Gavieside in 60-years’ time to assess how its residents have embraced the 20-minute neighbourhood concept.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 20-minute neighbourhoods undoubtably make day to day living easier but for communities like Craigshill the problems are not linked to the walkability of the place but much deeper socio-economic and health challenges.