As highlighted in an earlier blog (

Jonathan Wallace, Town Centres: A Time for Change), the high street is finally climbing up the political agenda. Although other issues – the housing crisis, climate change and of course Brexit - remain at the top of the list, the Government is, at last, waking up to the fundamental change being experienced in our town centres.

We now have a High Streets Minister (Jake Berry) who, to his credit, set up an expert panel led by Sir John Timpson – of the shoe repairs chain, a staple of many high streets across the country. This panel published their recommendations in the

High Street Report in December 2018. These included the creation of a High Streets Task Force to share information and expertise across the country, the Future High Streets fund (which has since been launched) and other short term solutions, related to town centre housekeeping, empty shops and parking.

In parallel to this work, the Government undertook a consultation on supporting the high street, with a number of changes to

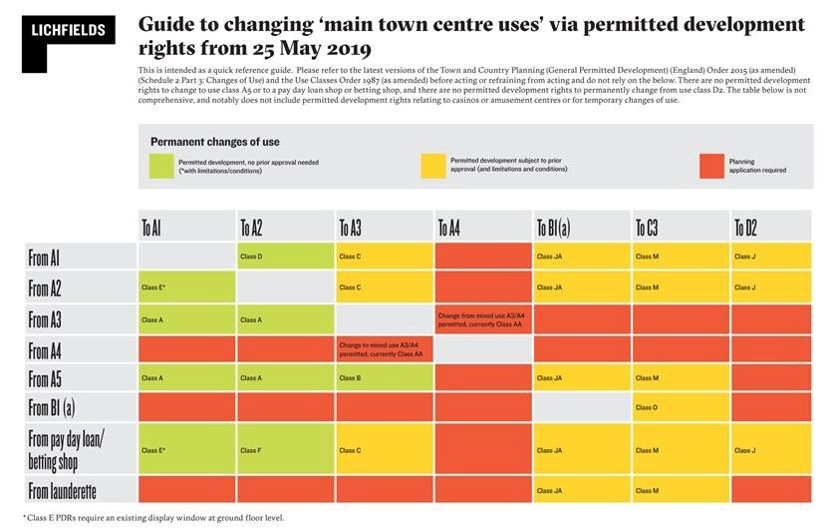

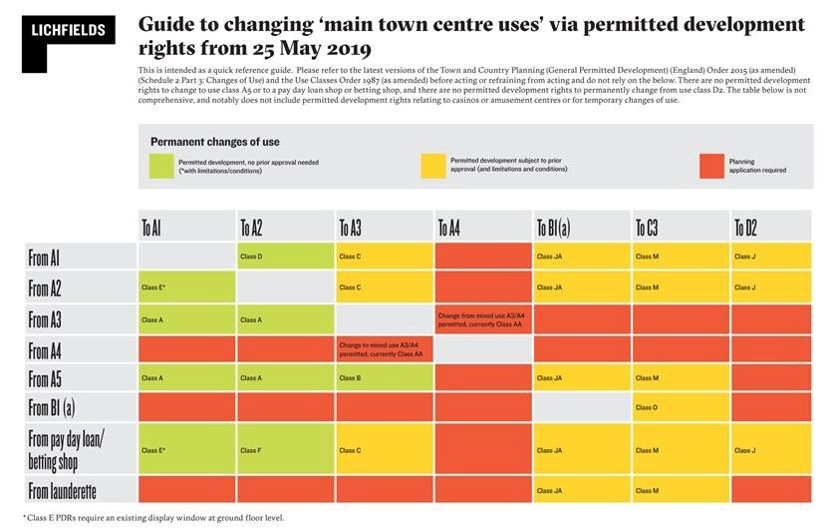

Permitted Development Rights (PDRs) being announced. These new rights, which came into force on 25 May 2019, allow:

-

shops (A1), financial and professional services (A2), hot food takeaways (A5), betting shops, pay day loan shops and launderettes to change use to an office (B1(a)); and

-

hot food takeaways (A5) to change to residential use (C3).

In addition to the above, the temporary change of use between commercial and community uses has also been extended from two to three years and the scope of the PDR extended to allow temporary change of use to certain class D1 uses. This is intended to give business and community organisations longer to test the market, before applying for a more permanent permission.

My colleagues

Steven Butterworth and

Jennie Baker previously asked the question - would the new PDRs really improve vibrancy in town centres? The additional flexibility this brings to help centres adapt to change is a good thing. In many areas, particularly those with higher vacancy rates and limited investment, a ‘laissez-faire’ approach which prioritises re-occupation of empty units will be appropriate. The temporary changes of use also allow authorities time to weigh up any potential harmful impacts before granting permanent permissions.

Some may have concerns that these recent changes could result in ‘dead’ frontages and/or that the new uses might not be ‘the right type’. Don’t forget, however, for permanent changes of use local authorities can use the prior approval process to consider the potential impact upon the provision of services or the sustainability of key shopping areas. Depending on the end use, they can also consider issues such as highways impact, noise, flooding, contaminated land and design/external appearance. Although perhaps more draconian, they also have the ability to impose Article 4 Directions which restrict PDRs.

Lichfields has provided a quick reference guide to the various PDRs for changing between main town centre uses. Inspection of the different permutations raises a number of questions, not least whether a simplified version of both the Use Classes Order and these PDRs would benefit everyone. Why allow a bank to change to an office, dwelling or leisure use, but not a café/restaurant? And why could a hot food takeaway or laundrette go to an office or dwelling, but not leisure use, which would contribute more to town centre vibrancy?

Rather vaguely, MHCLG confirmed in May that they will ‘amend the shops use class to ensure it captures current and future retail models’. This will apparently include clarification on the ability of the A use classes to diversify and incorporate ancillary uses. It remains unclear, though, whether the Government will merge A1, A2 and A3 to create a single use class. Whilst keeping A3 uses separate makes more sense, it would be strange if Classes A1 and A2 were not merged, when you can already switch between the two without seeking prior approval.

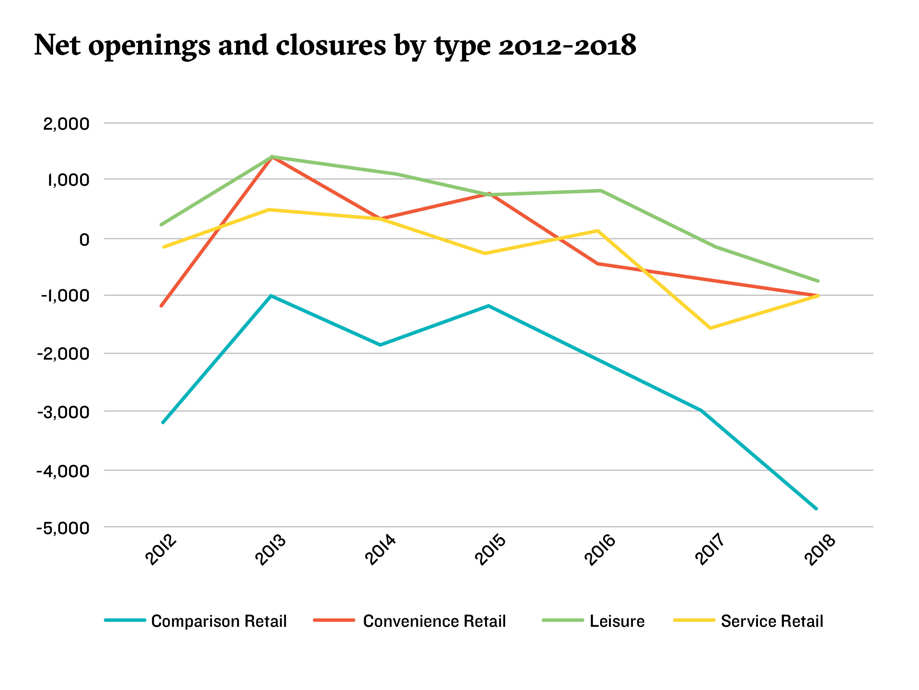

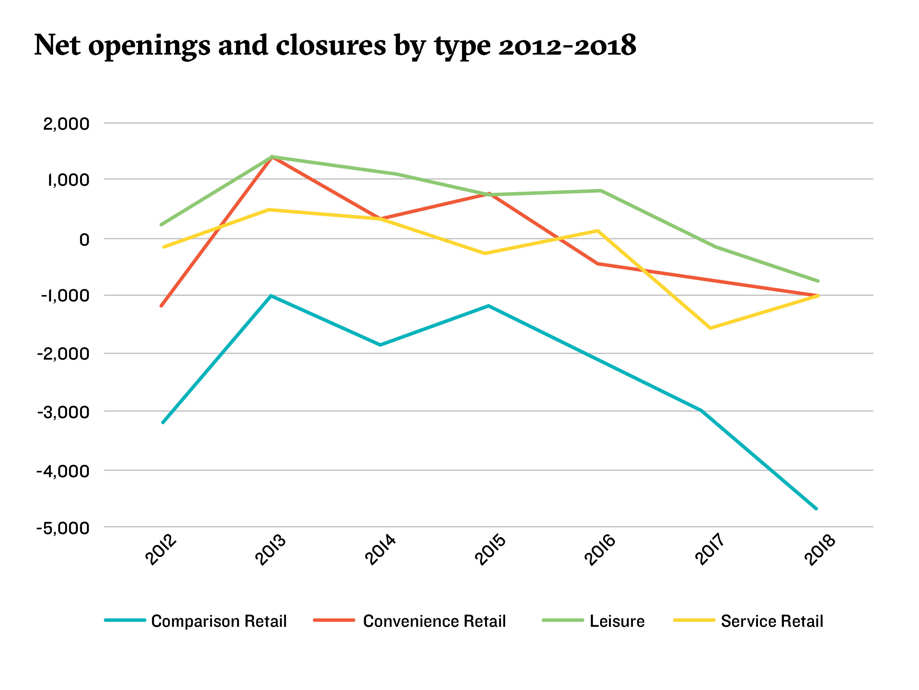

Source: Retail and Leisure Market Analysis Full Year 2018 (Local Data Company – May 2019)

Whatever the outcome, local authorities cannot rely upon PDRs to promote the future health of town centres. A more flexible policy framework and approach to determining planning applications is critical. Too many Councils are still developing overly prescriptive policies relating to frontages and protecting Class A1 uses. Primary Shopping Areas will continue to have role in the larger centres but their role and composition must be re-imagined. How many more high profile retail chains need to fail before we recognise the need for new anchors for our town centres?

There is no doubt more to come from the Government on this topic. Reliance by Councils on further PDR changes will only go a limited way to addressing the challenges town centre are facing. However, a more flexible and pragmatic approach, allied to a longer-term vision of what their town centres can be in future, and use of the many tools local authorities now have their disposal, could help to provide a catalyst for their revitalisation and re-imagination.