As we begin to chart a course out of the COVID-19 storm, we can be sure that the economic harm of the pandemic will be felt unevenly across the country, just as health-related impacts have varied significantly across our cities, towns and rural areas. The all-encompassing nature of the pandemic means that economic impacts at a local level will be influenced by a wide mix of factors, many of which are still unfolding and will inevitably change over time as restrictions are gradually eased but risks remain. These include local representation or exposure to sectors severely affected by the period of lockdown, performance of key locally-based employers, and the extent to which the local labour force has been able to work from home and maintain productive capacity whilst formal working environments were closed.

All this poses a strong risk that the economic crisis and impending recession will worsen existing regional inequalities across the country and potentially widen the North-South ‘economic divide’ which had been growing coming into the pandemic; a

recent report by the government’s Industrial Strategy Council found that regional productivity gaps are now as wide as they were in 1901, typically have deep roots and are long-lasting.

As explored in my previous Lichfields blog, tackling the UK’s spatial disparities had risen to the top of the public policy priority list, prompting the government’s so-called ‘levelling-up’ agenda; a key manifesto pledge designed to increase investment and improve life chances for communities particularly in northern and central areas, and one that featured prominently within the March Budget (which now seems a lifetime ago).

So where does COVID-19, and the unprecedented economic shock waves it has caused, leave this challenging and highly political agenda? Whilst the limited availability of official data and tangible evidence makes it difficult to gauge whether regional disparities will widen or not, there are some early indications which help to build a picture of potential spatial effects, summarised by theme below:

- Unemployment: ONS claimant count data released in May shows a large increase in people claiming unemployment benefits between March and April 2020 (capturing the first few weeks of the lockdown up to April 9th), but also that cities and large towns with weaker economies in the North and Midlands have been hardest hit by short term job losses.

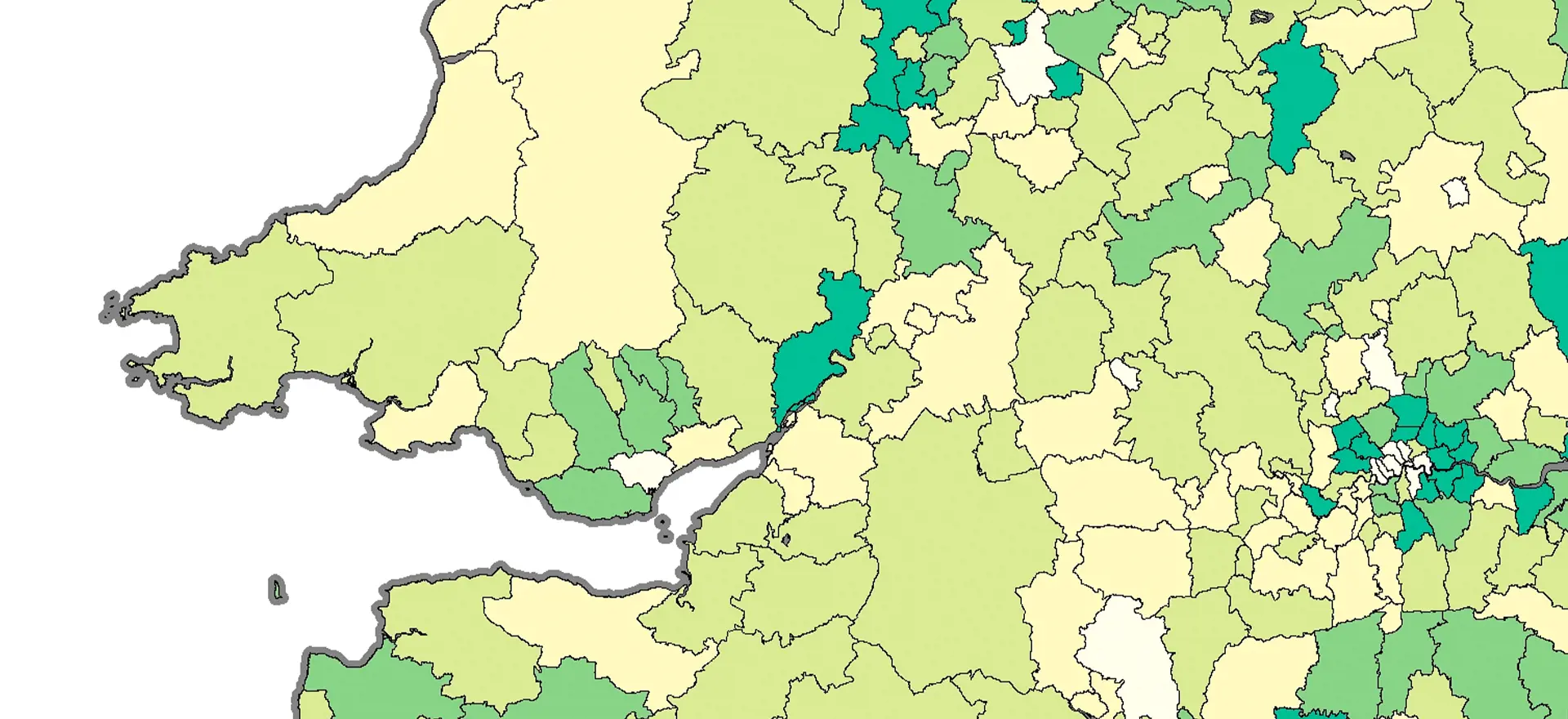

- Jobs at risk: nearly 8.7 million workers have been furloughed through the Government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, equivalent to around a quarter of all workforce jobs in the UK. Data released by ONS and HMRC last week shows that take-up of the scheme has varied significantly across the country, with high proportions of the local workforce currently furloughed in parts of the West Midlands, the North West, Essex, Scotland’s Central Belt and a number of outer London Boroughs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Take-up of Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme by Local Authority

Source: Lichfields analysis

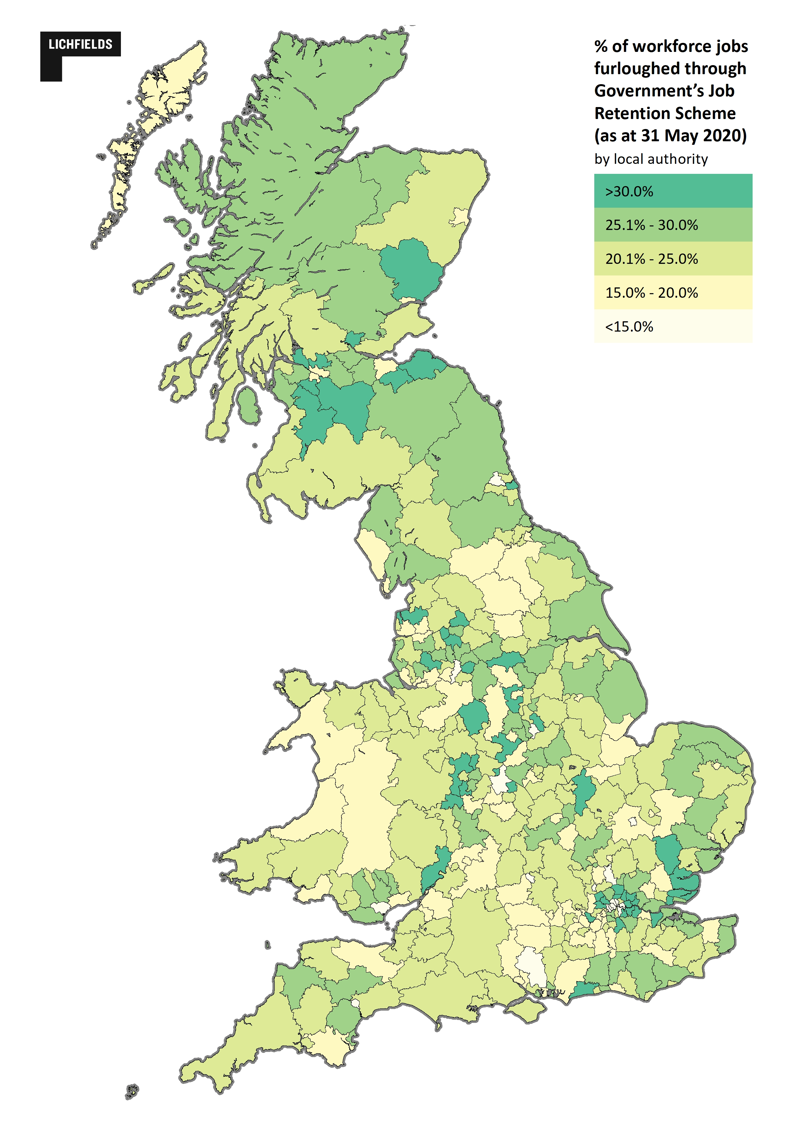

- Sector mix: Lichfields’ Local Economic Risk Index (summarised in Figure 2 below) suggests that many coastal and rural areas appear to be at greater potential risk of economic harm in the short term, reflecting the dominance of tourism, leisure and hospitality sectors within their local economies. Some short-term forecasts expect the gap between performance in London and the rest of the UK will widen this year; for instance, KPMG predict that the West Midlands will feel the biggest impact of the pandemic in 2020, largely as a result of the area’s automotive manufacturing industry which faces severe supply and demand side disruption from COVID-19.

Figure 2: Local Economic Risk Index

Source: Lichfields analysis

- Home working: London and the South East have a greater share of workers able to adapt or shift to home working to continue generating economic output during the pandemic. Larger proportions of low-skilled self-employed people in cities outside South East England could also make it harder for the economies of these places to recover.

- Self-employment: the economic impact on self-employed people has received much attention given their association with sectors most affected by COVID-19 so far, and self-employed people in the North and Midlands are more likely to be in less secure, lower-paid roles at high risk from economic shocks.

- Deprivation: existing patterns of deprivation and economic exclusion mean that many coastal and ex-industrial towns right across the country lack the resilience to cope with, and respond to, the effects of COVID-19, with many already suffering from economic decline, social isolation, a lack of investment, under-employment and poor social wellbeing.

- Household debt: People in large cities and towns in Northern England and Wales have particularly high levels of household debt making them especially vulnerable to job losses and furloughing.

Taken together, this snapshot of indicators suggests that the government’s ambition to level-up prosperity across the UK could face a significant setback as a result of COVID-19, with large parts of the North and Midlands plus other already struggling locations particularly vulnerable to the economic ‘scarring’ effects of both the immediate economic shock and the longer-term recession.

Yet spatial effects are unlikely to be clear cut and will play out differently as we progress through the various waves of this pandemic. It is tempting to assume that London and the South East are far better placed to withstand the worst effects of the COVID-19 economic crisis, but the Capital has some of the highest recorded numbers of virus cases and is disproportionately reliant on public transport to get commuters to work, which could undermine its ability to ‘bounce back’, at least as long as social distancing remains part of the normal way of life. And those areas hardest hit initially are not necessarily the most vulnerable places in the long run;

Centre for Progressive Policy analysis suggests that while parts of the North of England and Northern Ireland will struggle the most over the long run, parts of the Midlands face the largest initial impacts from COVID-19 and the associated economic shutdowns. This reflects the initial economic hit being driven by sector concentration within local areas (such as manufacturing in the Midlands) rather than underlying factors that support local resilience to economic shocks such as a high level of skills, low unemployment or a speedy recovery from a previous recession.

Whilst government’s immediate response must focus on survival and shoring-up those places most severely affected by the first COVID-19 economic shock wave, attention will eventually turn to those political promises it was elected to deliver. Levelling-up prosperity and opportunity across the country will need to become an essential part of the government’s economic recovery plan to mitigate the longer term, subsequent wave effects of what could be one of the deepest recessions on record.

History suggests that major pandemics can act as a ‘levelling’ force to reshape society by reducing economic inequalities

[1], so it could be that COVID-19 presents an unforeseen, yet timely, opportunity to re-appraise and reconsider how best to balance national economic growth as the country looks to re-build over the coming months and years.

This might include a more nuanced approach that complements ‘big ticket’ infrastructure spend (on things like transport, housing and digital) with investment in some of the wider critical ingredients that places need to prosper such as a responsive skills system (particularly if unemployment rises significantly), a business environment that induces innovation, and a more concerted effort to join up and implement the various Local Industrial Strategies being prepared across the country to give those places falling furthest behind on productivity the chance to achieve the step change they need.

Lichfields is currently working with clients across the country to help navigate a route to development and economic recovery from COVID-19. Please

contact us if you think we may be able to support your requirements.

[1] Walter Scheidel, The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century, 2017