This blog takes a closer look at the potential implications of emerging policies for embodied carbon in planning. It follows on from Lichfields recent

insight on the role of the planning system in targeting net zero. This showed that 35% of emerging plans issued in 2021 have policies which now reference a need for applicants to identify how they are addressing embodied carbon in bringing forward development. A further 24% have reference in supporting text to a more general ‘climate change’ policy.

Figure 1: % of Draft (Reg 19) Plans published between January and October 2021 identifying named ‘standards’ to address Climate Change in draft policies or in the supporting text of draft policies

In November the Environmental Audit Committee (EAC) held its third evidence session exploring the sustainability of the built environment and embodied carbon

[1]. The Committee heard from industry experts over two panels. The first discussed the sustainability of different building materials on offer, including concrete and steel to timber. The second panel explored how the planning system and building regulations can facilitate a sustainable built environment.

Previous evidence sessions have focused on embodied carbon and the retrofitting and reuse of buildings. In October

[2], the EAC heard disappointment from panellists that the Government had not gone further with its heat and building strategy

[3]; the Government’s Response to the Committee on Climate Change Annual Report

[4] and the Government’s Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener

[5] in terms of regulating and calculating embodied carbon.

The increased emphasis of thinking about whole life carbon as part of development was recently the subject of a

Parliamentary briefing note[6]. It details that many stakeholders, including the Climate Change Committee, now consider it imperative that an increased focus is given to the whole life carbon emissions of buildings, including embodied carbon emissions in order to address aspirations for Net Zero.

The importance of the emissions from buildings was recognised at COP26, with a day dedicated to ‘Cities, Regions and Built Environment’.

National Planning Policy: Towards Net Zero?

In terms of the Planning White Paper and outline of Planning Bill the EAC committee heard criticisms that Government appeared to be failing to adequately reflect the role planning has in delivering Net Zero. There were also calls for the NPPF to make Net Zero a fundamental common thread throughout it and to recognise the wider role planning has alongside changes to building standards.

If we are to meet the UK’s target of Net Zero emissions by 2050 it is evident that there is a need to look at the environmental impact of buildings in Britain and focus specifically on strategies to reduce whole-life emissions of buildings. However, there are currently no statutory requirements to measure or to reduce the embodied carbon emissions of buildings in the UK.

So what role can and should the planning system play in this? How is embodied carbon measured? How should the planning system make decisions weighing up issues the issues of embodied carbon against other development plan priorities? And how might the role of materials be used in development change?

Policies for Whole Life Carbon Assessments

A whole life approach to carbon emissions reduction includes tackling embodied carbon emissions alongside operational carbon. This approach has implications for:

- building design and materials selection;

- designing with less material to improve resource efficiency and reduce waste; and

- selecting materials with a lower carbon impact.

With the life cycle approach each material should be chosen only when it has the best performance compared to other materials and has the lowest whole life carbon impact. Materials with a higher embodied carbon could be considered only if a reduction of the operational carbon over a building’s lifetime can be achieved.

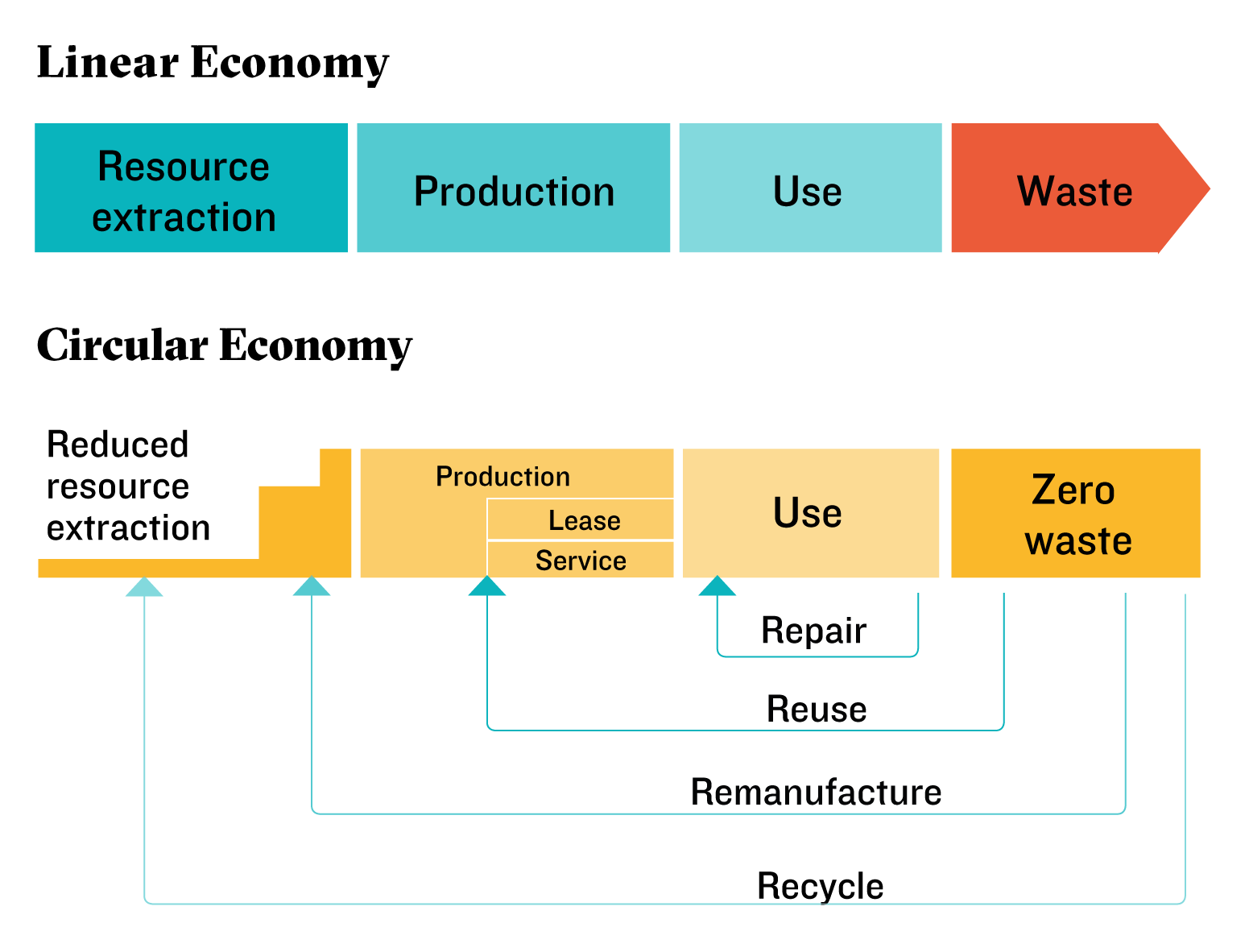

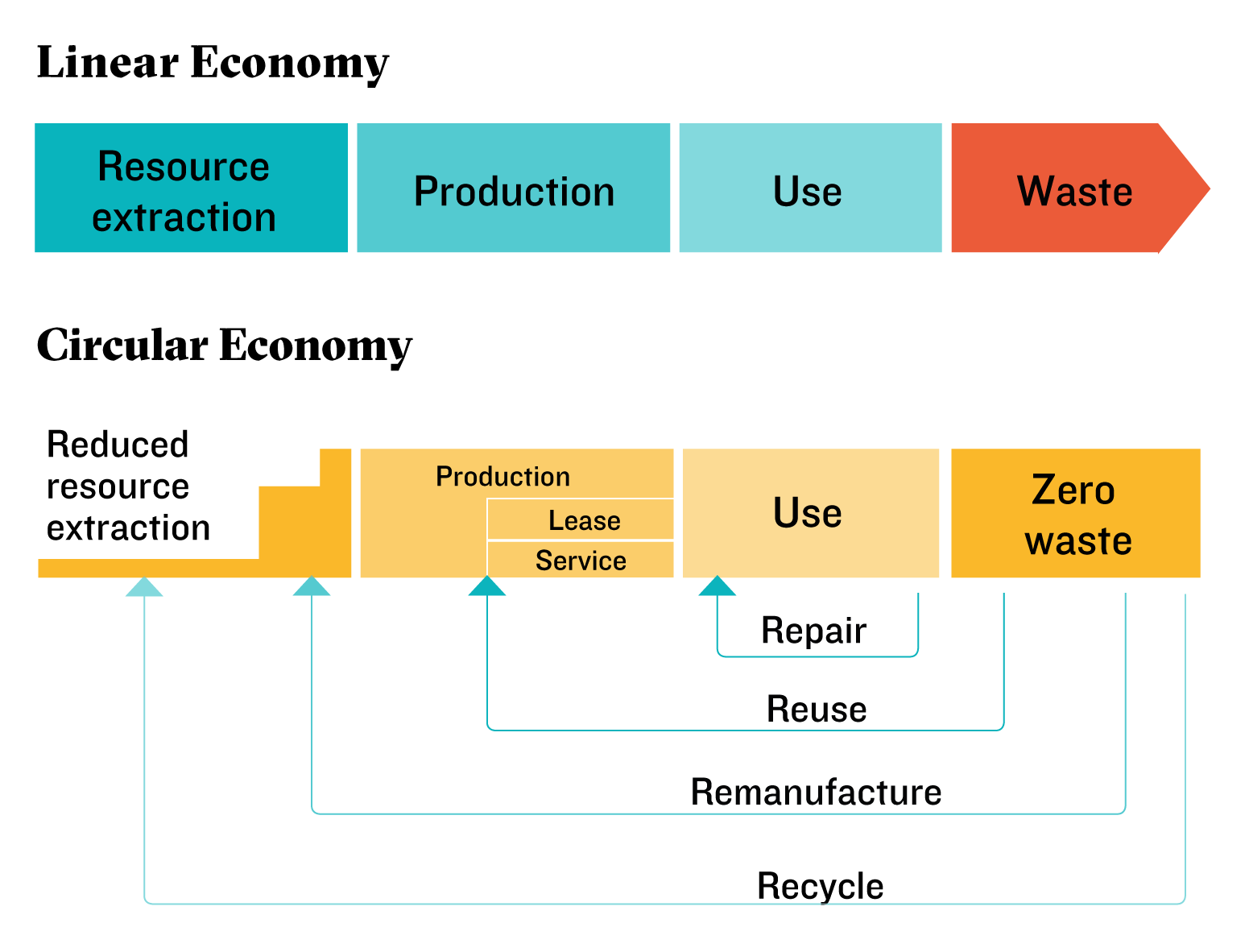

Circular economy based strategies, such as reusing materials and designing buildings to be adaptable or able to be deconstructed, can also contribute towards whole life carbon emissions reductions. The key difference between a linear v’s circular economy approach, is the shift away from waste (completely) with the drive towards repurposing and reuse. For developments, this means ‘new build’ needs to look not only as construction techniques, materials and flexibility of use over lifetime, it also anticipates enhanced management of asset to maintain materials for longer. For the development industry, it also means prioritising retrofit or refurbishment of existing buildings over new builds.

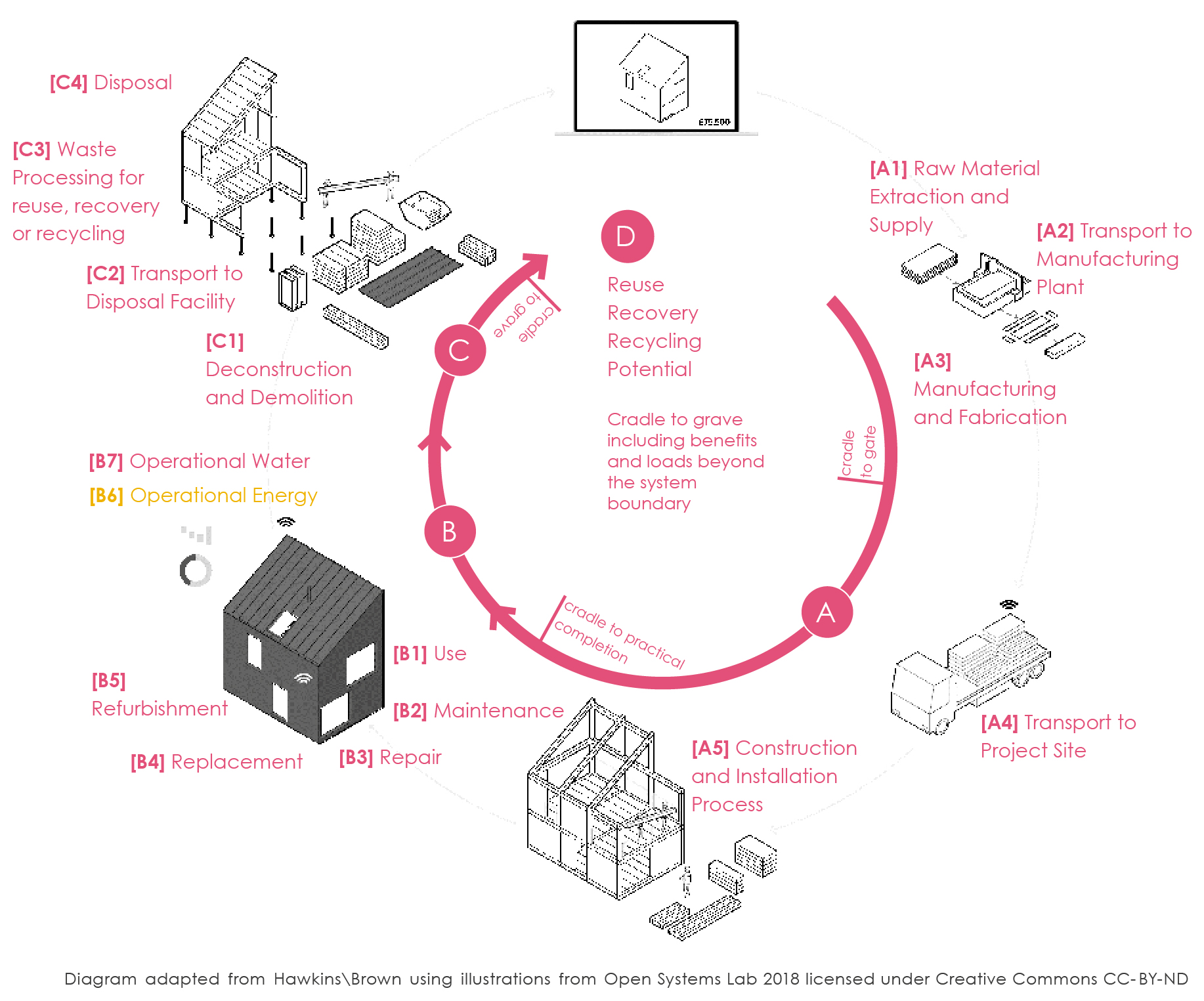

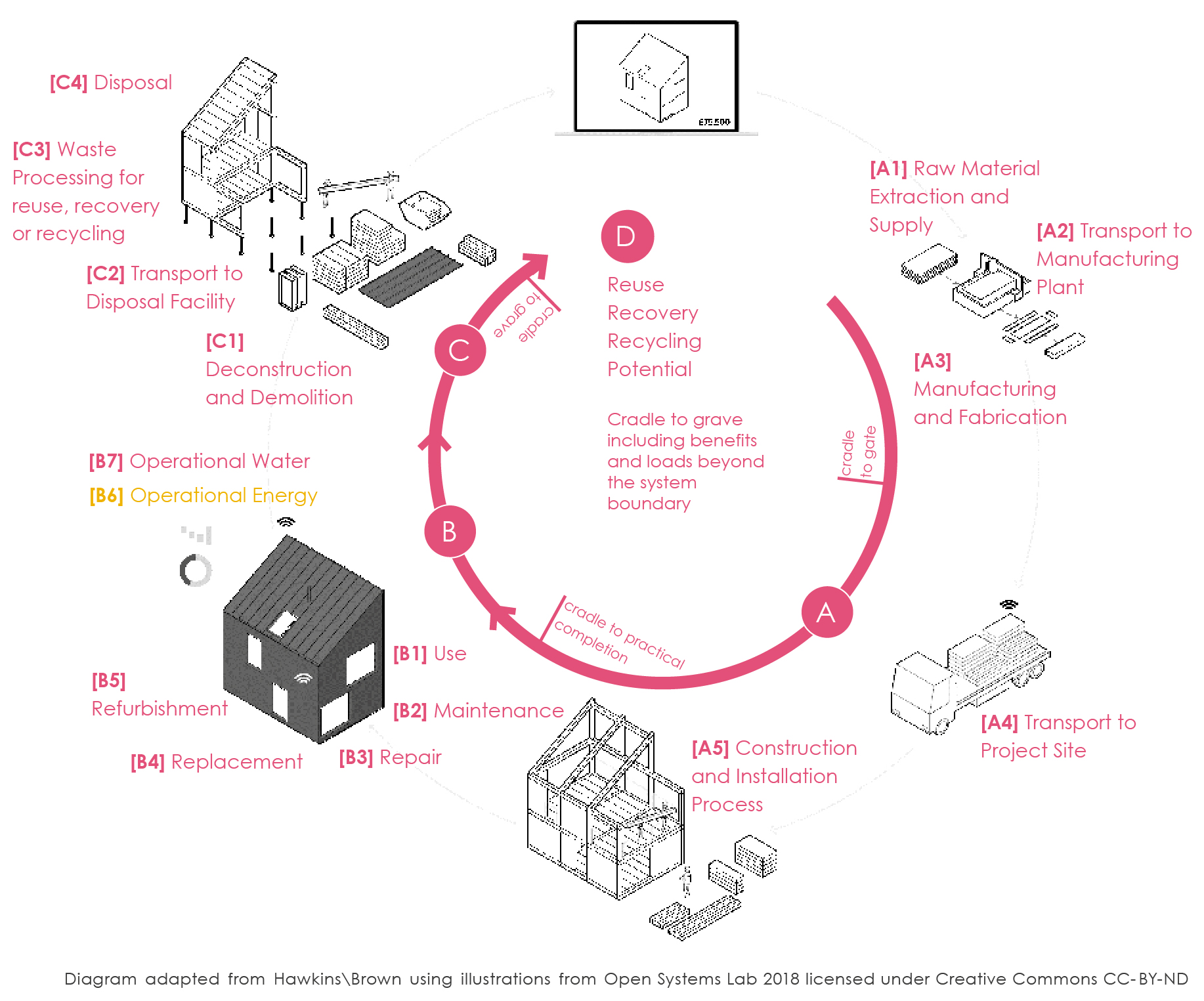

Considerations of a life cycle assessment is shown on Figures 2 and principles of a circular economy in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Considerations for measuring whole life cycle impacts

Source: LETI Embodied Carbon Primer illustrating considerations for measuring whole life cycle impacts

Figure 3: Circular v’s Linear

Source: LETI Embodied Carbon Primer showing the principles of a circular economy

Lessons from the London Plan

Previous Lichfields

blogs have explored London’s response to date on the climate change crisis and reviewed findings of the Climate Change Committee’s 2020 report to parliament.

More recently, following the adoption of the London Plan in 2021, we reported on its policies requiring all new developments to now

‘calculate whole lifecycle carbon emissions through a nationally recognised assessment and demonstrate actions taken to reduce them’ (Policy SI 2, Part F).

The London Plan has done on whole life carbon, it is one of the most important things that has happened in this country on this topic. It is a complete exemplar of what we need to be doing around the country.

Will Arnold, Head of Climate Action, Institution of Structural Engineers, giving evidence at EAC Committee November 2021

The London Plan approach was described by panelists as a an ‘exemplar’ of what we need to be doing around the rest of the country. By requiring teams to assess whole life carbon at concept / early stages in the project, it allows key decisions on carbon embodiment to be incorporated in the DNA of the development.

The GLA approach also requires whole life carbon to be looked at pre-app stage, at planning stage and post construction. The information is reviewed and it is compared with the benchmarks

[7]. There is an opportunity for carbon offsetting in exceptional circumstances.

Materials to consider

The November EAC Committee also heard evidence on how the Government can encourage sustainability of buildings that are being designed and constructed now and in particular the materials that are being used. With regards to materials the consensus from the panel is was there is: “no evil or sainted material”. That is there is no single solution that suits all low embodied carbon buildings. What the evidence session demonstrated was the myriad of considerations that designers need to take account of when selecting materials. For example: strength and durability; safety and insurance considerations (i.e. with timber); availability of materials within UK; and potential to dismantle and reuse (particularly steel vs concrete structures).

The panellists were asked if there are enough tools available to understand the carbon impact of materials that are being commissioned, used or deployed? It was acknowledged that the tools and the data is already there. What is needed is more transparent data, for example a with a centralised national database of measurements. Ideally the database should stretch across the lifecycle of a product or a material so that they provide the whole picture when specifying materials. The Government also setting a maximum embodied carbon per square metre, per building type, was considered as a response by Government that would be incredibly helpful.

Lichfields Commentary: Implication for planning

Understanding a development’s whole life carbon impact, including embodied carbon, is increasing in importance. Will the Government follow the lead of the London Plan and require all major developments to include whole life cycle carbon assessments? Will the Government take bolder steps with revisions to the NPPF be revised to better address climate change and net zero? Could we see a national targets set on embodied carbon? Or will it be left to local plans?

Planning has a front and central role to play in this. Importantly, at the same time planning also has an economic, social and environmental position that needs to be carefully navigated.

For developers, the financial case for sustainable buildings is now better established. The NLA reported research undertaken just before the pandemic showed that demand for sustainable office spaces was increasing and sustainable buildings in central London have a rental premium between six and eleven per cent

[8]. So certainly there is more of an inclination in the industry to embrace sustainability.

At the same time socially, it is understood that there is a correlation with net zero aspirations and creating spaces which support well-being and health (e.g. in terms of air quality, ventilation, the use of natural materials, and access to nature). Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance agendas are also now being taken increasingly seriously among developers, landlords and occupiers, as these three factors become mainstream in measuring the sustainability and social impact of investments

[9].

Decision makers (planning officers and members) want to encourage the most sustainable buildings and make decisions in an informed way, which helps them address climate challenge and work towards net zero targets. There is a need for upskilling to support understanding of developments’ climate change impacts. At the same time this should recognise that decisions prioritising embodied carbon in emerging designs have knock on implications for developments.

For example, a challenge of existing buildings is that they already have significant levels of embedded carbon. For planners, there may need to be a careful balance struck when retrofitting between retaining and reusing parts of the building, e.g. the steel or concrete structure, whilst not compromising future function like optimal floor layouts and generous ceiling heights. In some cases this may also mean other development plan policies need to also be ‘balanced’ if compliance with car parking, servicing or amenity policies cannot be achieved.

The EAC discussions also asked if there was a greater role for permitted development rights to make better use of existing building stock, with 600,000 vacant buildings in the UK. The feedback from panel was apprehensive due to concerns with inconsistency of quality of spaces created (e.g.in case of single aspect buildings or with lack of natural light). How do you encourage buildings back into use and still create quality spaces?

Ultimately is it better to have a well performing whole carbon assessment but which compromises on other policy requirements? How should these be balanced with other planning considerations? If you retain and reuse a building or structure there are constraints, which require compromise…

… or should the balance now be tipped in favour of addressing climate change?

[1] https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/62/environmental-audit-committee/news/158900/net-zero-buildings-what-materials-are-on-offer-and-how-can-the-planning-system-support-sustainability/

[2] Embodied carbon and retrofitting policy under the microscope by MPs - Committees - UK Parliament

[3]Heat and Buildings Strategy

[4]Government Response to the Climate Change Committee

[5]Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener

[6] UK Parliament Post, Reducing the Whole Life Carbon Impacts of the Building, November 2021

[7] Rhian Williams from the GLA London Plan team speaking at the EAC also confirmed the intention of the Mayor to publish the final version of the Whole Life-Cycle Carbon Assessments guidance in the New Year.

[8] JLL, The Impact of Sustainability on Value (2020), p. 5. Cited in NLA, WRK/LDN: Office Revolution? (2021)

[9] NLA, WRK/LDN: Office Revolution? (2021)