‘Planning for the Future’ – launched on 12 March - is a starter for ten on how to deliver one million beautiful homes in brownfield locations in the first instance, by the mid-2020s. The Statement was published after an oral statement was made in the House of Commons by the Communities Secretary, the Rt Hon Robert Jenrick MP (SoS).

There is no mention of measures unrelated to housing delivery, although some of the proposals will benefit commercial development too.

This is a somewhat tempered follow-up to the Treasury’s promise in the

Budget to ‘explore long-term reforms to the planning system, rethinking planning from first principles, to ensure the system is providing more certainty’; it promises a comprehensive review of what does and doesn’t work, but not diving straight into planning reforms that might throw out the baby with the bath water.

It is a prelude to the Planning White Paper, which will look to modernise the planning system, speed decision making and “make it easier for communities to engage and play a role in decisions which affect them”. The White Paper was due by June, but this date and probably all dates referred to must be in question given current Coronavirus-related events.

Given the Government’s equivocal view on some policy areas - likely to be being fleshed out for inclusion in the White Paper - it decided to announce the changes it was more certain about in the Statement, which range from confirmations of immediate approach through to more distant policies, such as the new 2023 local plans deadline.

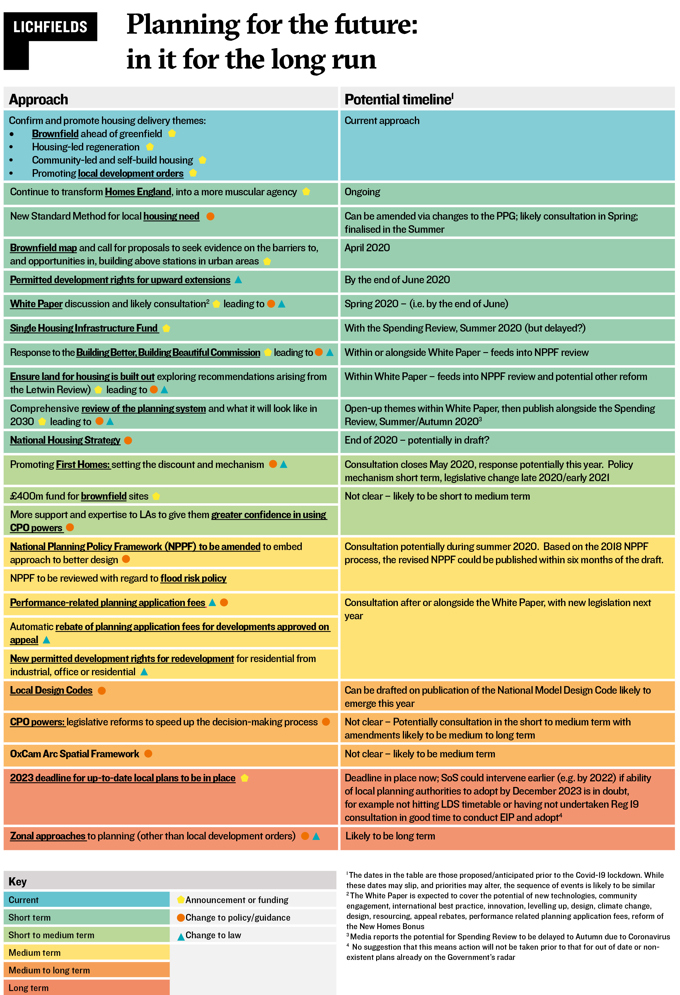

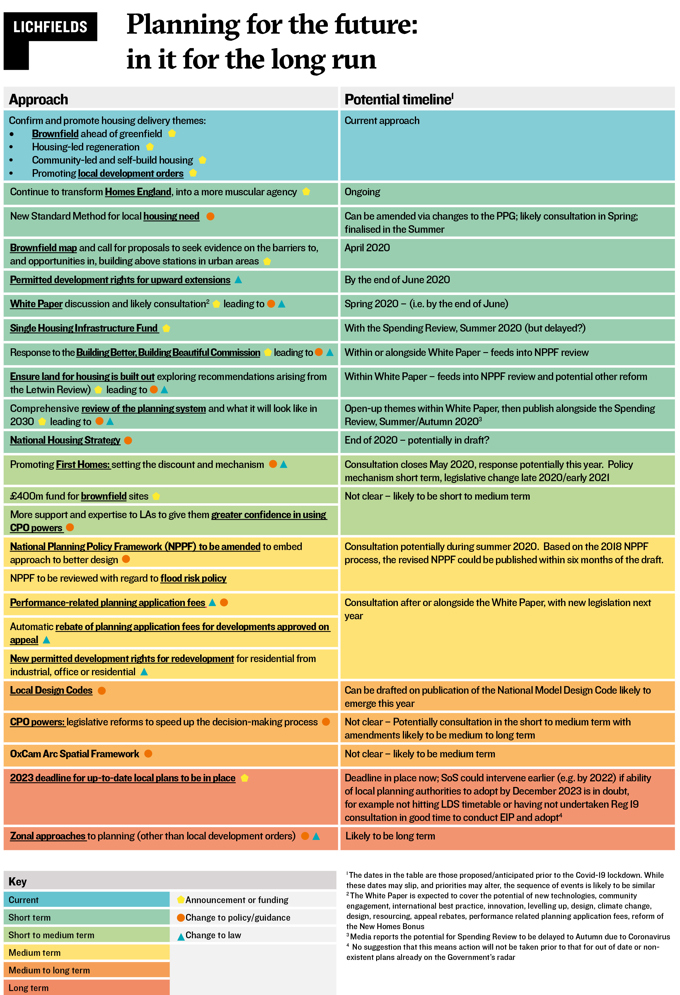

This blog covers a lot of ground, so our timeline here will assist in navigation; it presents the main proposals and speculates on potential timescales for their introduction – click on the image to enlarge it, which will allow you to follow a link to take you to our commentary on each item. The dates in the table are those proposed/anticipated prior to the Covid-19 lockdown. While these dates may slip and priorities may alter, the sequence of events is likely to be similar.

Notable absences are direct reference to a new Planning Bill (albeit it is inferred by the nod to comprehensive reform) and any change in approach to the Green Belt. There are plenty of references to local but – interestingly - none to localism or neighbourhood planning, although neighbourhood forums are mentioned in the context of community and self-build. The desire for a plan-led system remains, but surprisingly the deadline for having an up-to-date local plan has rolled back into the middle distance – perhaps due to the range of reformed planning polices they will be expected to incorporate?

In this blog we provide a way finder for the potential direction of policy and flag some practical implications. However, this is just a start: the Government has kicked off a conversation about planning reform that will take us through the Summer (perhaps beyond) and lead to a suite of new national policy and guidance, hopefully no later than the end of this year (working with the grain of the existing planning system) and potentially new legislation to follow; the extent to which this leads to more radical reform (as per Policy Exchange’s

Rethinking Planning for the 21st Century) is open to question.

Government will wish to engage with all participants in the planning system over coming months to help shape these reforms, ensuring the formulation of policy supports rather than hinders housing delivery. Lichfields can assist those wishing to engage with Government through our advice and research capabilities and we can help facilitate wider discussions with policy makers and practitioners. Please get in touch.

Brownfield first

Whilst seeking the delivery of more housing, the Statement pursues a brownfield-first approach. This includes the investment of £400m to “use brownfield land productively”, publication of a national brownfield map, and encouragement of building upwards and increasing density. In his statement to the Commons, the Communities Secretary stated that “We absolutely we want to have a brownfield-first policy—that is at the heart of everything that we are trying to do in this policy area”. However, he added that “we have to balance that with ensuring that homes are available for the next generation in those parts of the country where people really want to live”. This is important given that any sensible estimate shows that the delivery of 300,000 new homes each year will require the release of greenfield sites as well as the redevelopment of previously-developed land.

Recognising that many brownfield sites incur abnormal costs which can threaten viability, the additional funding to support the redevelopment of brownfield land for housing is welcome. However, further clarity is needed on what this will be used for and how it will be distributed; the indication that it will be used to work with ambitious mayors and local leaders suggests it is a fund for combined authorities and areas with clear growth ambitions.

The principle of increasing density (on brownfield sites) in urban areas in line with local character and to make the most of local infrastructure represents an important source of housing supply. However, it will be important that this delivers the

types of housing that the market requires: family housing with gardens, housing for those with specific needs, and housing for older people; too often local plan policies can result in a monomaniacal race for high density at the expense of a balanced community approach, and interestingly, a day after his Statement, the Secretary of State intervened on the London Plan

[i] to specifically include reference to providing homes for families.

Timescale: short term via planning application, long term via the local plan.

Extended permitted development rights

The Government has also proposed intensification and change of use of previously developed sites via permitted development rights; both types of new permitted development right (PDR) proposed have been kicking around for a while.

Adding storeys

It is intended that by the end of June there will be a PDR to add up to two additional storeys to residential ‘blocks’ to provide ‘new and bigger homes’. The conditions and limitations are not listed. When upwards extensions in London were consulted on by the Cameron Government and the then Mayor of London (a certain Boris Johnson)[ii], one option was for the PDR to be obtained via prior approval. The consultation outcome opined that prior approval would have been no less onerous than a planning application and instead a supportive paragraph was to be included in national policy (see paragraph 118e of the NPPF). Based on that previous consultation, prior approval requirements for current PDRs and para 118e, the additional storeys PDR might be:

-

subject to prior approval and a neighbour consultation

-

not permitted to exceed the prevailing height and form of neighbouring properties and the overall street scene

-

required to be well-designed (including complying with any local design policies and standards)

-

required to maintain safe access and egress for occupiers

-

not available to listed buildings and other heritage assets – and perhaps buildings within their ‘setting’.

Our Heritage Director, Nick Bridgland, notes that the additional storeys PDR will change not only the skyline, but the potential skyline. The baseline for determining the impact of a new building on a heritage asset or conservation area will change if the skyline in the vicinity could increase by two storeys without planning permission. This would need to be taken into account in assessments of heritage and visual impact.

Timescale: Short term

Right to rebuild

Office to residential permitted development, now in its seventh year, has been effective at swiftly converting office space to residential space, although accompanied by widespread concern at the quality of some dwellings, the loss of office accommodation and the challenges it created for land assembly in some regeneration areas. While there is no immediate suggestion this permitted development right is to be modified, rates of take up have slowed significantly as the most obvious sites have already been converted or have obtained a prior approval that provides a fallback position for an alternative planning application.

Enter stage right a potential permitted development right to demolish a vacant office, industrial or residential building and redevelop the site for residential. This potential right has been suggested by the various Governments several times since October 2015[iii] and it appears MHCLG officials have been plugging away on a PDR secured by prior approval that can been drawn tightly enough to address the concerns of Tory opponents. This will be all the more important given the ‘Building Beautiful’ agenda.

‘Living with beauty: the report of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission’ (the BBBBC report), makes specific reference to the design related concerns surrounding office to residential PDRs and includes recommendations to on how to define PDRs that result in well-designed homes and ‘betterment’ i.e. payment of planning obligations or CIL:

“Where it is appropriate, to build housing via permitted development rights or permission in principle should require strict adherence to a very clear (but limited) set of rules on betterment payment and design clearly set in the local plan, supplementary planning document or community code as set out above. If these rules are followed, then approval should be a matter of course. There are precedents for this. For example, permitted development rights for residential extensions requires matching materials”.

The Commission also recommended moving minimum room or home sizes into Building Regulations and:

“that adherence to established design guidance, coupled with a certification process, not unlike the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (‘BREEAM’) but directed to the sense of place, is embedded into an overhauled ‘prior approval’ process”.

The Government has indicated that it supports the approach of the BBBBC report and will take much of it forward. This obviously does not mean wholesale adoption of recommendations, and it has not indicated that a new residential redevelopment PDR would require planning obligations. However, the residential redevelopment PDR would lead to a CIL payment due to the new floorspace, albeit some of this might be offset by existing floorspace and the usual exemptions and reliefs would apply.

Similarly, while there is no reference by Government to compliance with the nationally described space standard, minimum space standards seem likely. The Government has previously stated that it is prepared to examine introducing these into the Building Regulations.

Another concern raised by the BBBBC is that it will lead to people living in “former offices on business parks miles from public transport”. With this in mind, the Government might consider limiting the locations in which the PDR would apply.

Accordingly, we await the detail within a future consultation on how developers will be able to replace without planning permission these vacant buildings ‘with well-designed new residential units which meet natural light standards’.

Timescale: Long term

Brownfield map

In April, the Government will launch a national brownfield sites map and "a call for proposals to seek evidence on the barriers to, and opportunities in, building above stations in urban areas” because “It is vital that we make the most of existing transport hubs". This suggests it could be used to bottom out (as far as one can) the scope for brownfield land to provide new homes, and may or not inform future policy direction.

A 2014 Lichfields analysis and mapping of the former National Land Use Database register of brownfield sites (reported in the IPPR Report ‘Closer to Home’)

[iv] revealed a “capacity of c.1m [homes] when needs over the next fifteen years are for 3.3m new homes. Even if there are further sources of untapped potential, the national gap is likely to be very significant”. More problematically, that “brownfield capacity is not concentrated in locations with the highest levels of housing need”.

Timescale: short term for issue, medium term for response and analysis

It’s the design, stupid

Notwithstanding the questions surrounding the proposed permitted development rights (see below), the Government continues to promote and seek to insist on high quality design.

In this regard, the NPPF is to be updated “to embed the principles of good design and placemaking” and “to expand on the fundamental principles of good design to define what is expected of local authorities and developers to support the creation of beautiful places”.

As noted above, the Government has not yet formally responded to the BBBBC recommendations (see our

England Planning News for February 2020), but has said it will take many of them forward. In the Statement and in the House the SoS focussed on tree-lined streets and giving communities greater opportunity to influence design standards, but there are a number of far reaching recommendations such as requiring a net gain in design terms (which in some respects already features in NPPF para 130) and local plans indicating scale and design features for strategic sites and ‘form-based’ approaches to site allocation rather than a land use focus and a fast track application process for ‘beauty’.

In the Commons, the Communities Secretary was clear on one element at least, referring to high rise clusters – with a nod to town centre retail consolidation - and densifying ‘gently’ elsewhere:

“One point it raises, which we will now be taking forward, is the need to mitigate against the urban sprawl and the damage to the countryside we have seen over the past 50 or 60 years and more.

The answer to that is gentle density in urban areas, building upwards where appropriate—perhaps where there are existing clusters of high-rise buildings—and, building gently where building upwards is not appropriate. There are plenty of examples in the report of where that can be done in an attractive way that local communities could support. We need to ensure more homes are built in our town centres and around our high streets. The high streets and town centres fund that we have created through the £3.6 billion towns fund provides funding to many parts of the country to do exactly that”.

‘Gentle density’ is recommended throughout the BBBBC’s report, which the Commission defines as “density that is achieved at street level and without presenting alien or impersonal structures that challenge the ordinary resident’s sense of belonging”, or perhaps more readily translated as being “associated with Georgian or early-Victorian urbanism”.

The Statement also refers to modernisation, which is a nod to modern methods of construction and the related need to upskill and expand the construction workforce. The SoS said in his Oral Statement:

“On the broader challenge relating to modern methods of construction, that will absolutely be at the heart of not just the planning work we are going to do but our broader housing strategy. There is a huge opportunity for us as a country to lead the world in new construction technology and to build good-quality homes at pace. I really want us to take that forward”.

Timescale: medium to long term, albeit design is now on decision makers’ radars

Identifying and meeting housing needs

The proposed review of the formula for calculating local housing need is welcome as a means by which to plan for an increase in overall housing delivery. It should also seek to address some of the shortcomings of the current methodology. As to what will replace it, the SoS response to Clive Betts MP in the House of Commons debate following his Statement to the House was illuminating:

“In reviewing local housing need, we will take account of the need to level up and rebalance the economy, both geographically, from the south to the north, and between areas—for example, by trying to ensure that cities that have depopulated in our lifetime can have more homes built in them to get people and families back into and living in some of our great cities where sadly fewer people are living now than 20 or 30 years ago”.

This hints at some of the changes that might emerge:

- A move away from outdated and volatile household projections – which are drifting away from the Government’s 300,000 homes per annum ambition [v].

- An approach focused on ‘levelling-up’ and boosting housing targets in the north of England

- Relating the level of need to the size of existing places, rather than trends in population, which will boost numbers in districts containing towns and cities rather than lightly populated rural areas.

The precise formula remains to be seen. Options will be being looked at. Some – including Lichfields – have advocated a ‘stock based’ approach where the assessment of need is proportionate to the number of dwellings in an area - rather than based on volatile projections - and secures a more stable ‘run rate’ of housing growth consistent with 300,000 homes per annum. In practice, this urban focus is likely to require a better mechanism for addressing unmet housing needs in urban hinterland where there is constrained land availability, and for securing Green Belt release in under bounded urban authorities.

However, in of itself, housing need is not enough: delivery must keep pace. So, the continued focus on the Housing Delivery Test is welcome; it will really start to have effect from November 2020 when the presumption in favour of sustainable development will apply to all authorities that have delivered less than 75% of identified needs. Other things being equal, around a third of all authorities in England are at risk of this most severe sanction based on last year’s figures.

If the Housing Delivery Test is the ‘stick’ for under delivery, New Homes Bonus (NHB) represents the ‘carrot’ to reward delivery. The Statement says: “the government will consult on reforming the NHB in Spring to incentivise greater delivery and ensure that where authorities are building more homes, they have access to greater funding to provide services for those who move into them”.

Since 2011, a total of £8.85bn has been allocated to local authorities under the NHB, an average of £27m per authority. But there is no clear evidence that the NHB itself – set at relatively modest levels per new dwelling - has stimulated additional housing delivery. To have a real effect, additional incentives should be offered to pro-active authorities, perhaps at the expense of those that fail to meet their needs, or in situations where a large proportion of housing delivery is the result of planning permission granted at appeal.

Timescale: short to medium term

Improving certainty and housing delivery rates

Several different measures set out work towards improving certainty for developers:

There were also measures to improve certainty for local planning authorities, in the form of reference to ensure land for housing is built out, including the ownership of land. The Statement to the Commons went further than the written Statement, saying “for the first time we will make clear who actually owns land across the country, by requiring complete transparency on land options. Where permissions are granted, we will bring forward proposals to ensure that they are turned into homes more quickly.” By contrast, the written Statement referred to greater transparency. What this means in practice is not clear; options are not the only contractual method involved in controlling potential development land; for example promotion agreements and joint venture vehicles are also common.

The Statement also refers to

exploring “wider options to encourage planning permissions to be built out more quickly” which suggests revisiting the recommendations of the Letwin Review, although Sir Oliver does not himself get a name check. There is some consistency between Letwin’s recommendations aimed at improving certainty and diversifying mix and the Government’s suggestions on zoning, stronger design codes, supporting CPO and reducing the homogeneity of housing on offer. However, some of Letwin’s recommendations about interventions and delivery structures seemed perhaps over-engineered/disproportionate and would mean it took longer for sites to start on site, so it will be interesting to see where this leads. Lichfields research –

Start to Finish – provides a good evidence base for considering build out on large-scale sites.

Plan-led planning: the focus remains, the threats move more distant

The Government continues to advocate a plan-led system, albeit shortened and simplified, according to the Communities Secretary. The focus is on these being up to date.

The latest statistics (1 March 2020) show 42% of authorities have an up to date plan that is less than five years old (see Figure 1).

Therefore, given this statistic and the local plan interventions currently taking place, it is interesting that the Government chose to say that it will ‘prepare to intervene’ where local planning authorities fail to meet the 2023 deadline for having an up-to-date plan. One hopes that they will start raising concern as soon as timetables start to slip (perhaps if a Plan has not gone out to Reg 19 Consultation by middle of 2022 or there is LDS slippage earlier than that).

The deadline of 2023 affects all local plans, as most will be become ‘out of date’ (i.e. more than five years old) between now and 2020. This is despite the Communities Secretary’s speech to Parliament inferring that 2023 was a deadline for ‘all plans to be in place’ as though there is a final position, rather than the rolling process required at least every five years by legislation and policy

[vi].

In practice, this announcement is more of a nod to the primacy of the development plan than a statement that will have impact on the ground: local authorities that prefer a plan-led approach will continue to seek an evidence based up-to-date solution, while those that do not will look to the 2023 threat of intervention.

The 2023 date allows for a time lag for significant changes arising from the current round of planning reforms including updates to national policy relating to design, revised local housing need approach and potentially flood risk and more. And while it won’t have informed the deadline, it will also allow a response to any unexpected consequences of any new permitted development rights.

As part of its approach, the Government should also focus its attention on closing the loophole that allows existing local authorities to ‘self-certify’ the review (as opposed to update) of plans for another five years without any scrutiny or testing. The

example of Reigate and Banstead shows the risks this poses to housing delivery in the south east.

The shift will also be linked to digitalisation of the planning system. The Government has been striving to digitise planning for several years and the BBBBC report (see above) links analogue planning to accessibility of the planning system generally:

“Planning needs to shift from being an analogue process to operate more effectively in a digital age. Clearer language and a lack of jargon should continue to be encouraged alongside greater use of imagery of possible development”.

The Communities Secretary said to the Commons:

“Plans are taking too long and we would like not only the time taken to produce them to be reduced significantly, but for people’s views to be genuinely taken into consideration. We are also, through our new digital agenda, seeing whether there are ways in which that can be done in a much more modern, 21st-century manner, on people’s smartphones, so that their views can be taken into consideration”.

A system that relies on local newspaper advertisements for community engagement is in dire need of reform.

Performance-related planning application fees

Proposals to increase planning application fees by relating them to a measure of a planning department’s past performance were mentioned in the 2017 Housing White Paper. The current proposals suggest a wholesale review of the approach to planning application fees, which would be linked to a performance framework “to ensure performance improvements across the planning service for all users”. More details are expected in the White Paper, expected in the spring.

Timescale: medium term

Avoiding delays arising from rogue decisions

Not mentioned in Parliament, the Statement says the White Paper will propose “to promote proper consideration of applications by planning committees, where applications are refused applicants will be entitled to an automatic rebate of their planning application fee if they are successful at appeal”.

This infers that the refund would only apply to planning refusals made by planning committees, but given its policy intention, it might only apply where Councillors overturn officers’ recommendations.

Lichfields research from 2018 found that for schemes of over 50 units refused against officer recommendations to approve, 35% were subsequently dismissed by Inspectors at appeal, suggesting the issue is as much about consistency of planning judgement.

If the refund did apply to all planning committee refusals (and why not, if officers’ recommendations are truly their own?) this might mean that schemes of delegation are altered so that fewer planning applications are considered by planning committee – an intended consequence perhaps?

Might it apply to all refusals of planning permission? This seems unlikely as it does not reflect the policy intention.

The refund could even be limited to schemes that include a residential element: between July and September 2019 74% of residential applications were approved by local planning authorities, dropping 3 per cent from the same quarter in 2018. LPAs approved 91% of commercial applications in the same period, but this also represents a decrease compared to the same quarter in 2018.

The Communities Secretary did not refer to the introduction of a paying a fee in order to appeal; a notable change in tack from the potential appeal fee capped at £2,000 to deter “unnecessary appeals” in the May Government’s 2017 Housing White Paper.

More recently, in December 2018, the Rosewell Review

[vii] noted that some developers supported appeal fees, if it would increase the availability of Inspectors. There was no specific recommendation regarding appeal fees in the Review, but the Review said that if were introduced they should be linked to performance outcomes and it was not clear at that time whether they would be necessary to deliver improvements.

Whilst resourcing has improved, and ‘Rosewell Review’ inquiries are at present being determined in 24 weeks on average, for other appeals written representations are taking 23 weeks, hearings 37 weeks and inquiries 55 weeks from validation to decision.

Timescale: medium to long term

Promoting Local Development Orders and other ‘zoning’ tools

The government plans to outline support for zoning tools, but only specifically refers to local development orders (an existing mechanism):

“The government will trial the use of templates for drafting LDOs and other zonal tools to create simpler models and financial incentives to support more effective use. The government has also launched a consultation on a new UK Freeport model, including on how zoning could be better used to support accompanying development”.

The BBBBC report also refers to use of a zonal approach for allocated or zoned sites, saying that “local authorities must feel empowered more confidently […] to define the form, density and standards of development that are (or are not) possible in specific areas.”

Interestingly, Policy Exchange’s recent report, Rethinking Planning for the 21st Century, co-edited by Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s special advisor on planning and housing, Jack Airey, recommended a radical shift away from the post-war system toward a “binary zonal land use planning system”, suggesting “development rules should be clear and non-negotiable, relating to development form and layout. […] These rules should not determine the fact of development, but they should consider the form of new development and how it retains and adds to an area’s sense of place”.

Local development orders

[viii] were introduced in 2011 and have received Government plugs at various times ever since. Their mention in the Statement in the context of expanding zoning tools is another such push. The BBBBC report noted “

local planning authorities have used few LDOs in some cases because doing so would lead to the loss developer contributions through of Section 106 payments”.

Neighbourhood Development Orders were notably absent from the announcement, but there is no indication that it is beginning of the end for Neighbourhood Planning; neighbourhood forums were mentioned in the context of promoting community and self-build housing.

Timescale: immediate for LDOs, which already exist. Long term for new zoning approaches.

Infrastructure first

The Statement reiterated the Budget commitments that reflect the Government’s infrastructure first manifesto commitment. The SoS said to the Commons “We need well-planned, modern communities, which is why we have invested through the housing infrastructure fund (HIF). We will be succeeding that with a new, larger and longer-term single housing infrastructure fund, which will ensure that at least £10 billion is available for local areas to plan for the future”.

The HIF, launched in 2017 has now closed and the Single Housing Infrastructure Fund will be brought forward with the Spending Review. Last year, we reviewed the HIF allocations up to May 2019 and where they had been allocated

[ix].

According to the Budget, the Single Housing Infrastructure Fund is intended to unlock new homes in areas of high demand across the country by funding the provision of strategic infrastructure and assembling land for development. The Statement says that “Homes England will engage with local authorities and the wider market to build a pipeline of opportunities up and down the country”. It also says that to underpin the Government’s work on planning reform, the different needs of different places balancing boosting supply and improving existing stock and decarbonisation targets (amongst other things) Homes England will continue to be transformed [with the policy and fiscal equivalent of a protein shake] “into a more muscular agency that is better able to drive up delivery”.

Timescale: short term (but likely to be available for several years)

Sustainability and flood risk policy review

The Government is to review the flood risk policy contained within the NPPF, which is part of a response to recent flooding events.

“We will assess whether current protections in the NPPF are enough and consider options for further reform, which will inform our wider ambitions for a new planning system”.

The proposed review sits alongside investment in flood defences. And in the written Statement it was included alongside the Future Homes Standard that has been consulted on and a proposed net zero development in the East Midlands.

In the Commons, the Communities Secretary confirmed that he would be working alongside the Environment Secretary with regard to flood risk measures and preserving the environment.

Timescale: medium term

Supporting home ownership

This is in three ways:

- a new shared ownership model

- explore encouraging a market for long-term fixed rate mortgages and

- First Homes.

Of these, the last is most relevant to planning. We have already blogged about

First Homes, a new minimum 30 per cent discounted sale housing product that might be achieved via changes to policy or law. The consultation on First Homes has been extended from 3 April to 1 May.

The Government says it will publish a Housing Strategy by the end of 2020 setting out plans for housing delivery and a “fairer housing market”. Whether or not this will be a consultation draft is not clear. The Statement says that the anticipated Planning White Paper, Social Housing White Paper, Building Safety Bill and Renters' Reform Bill will form the “bedrock” of the Housing Strategy.

Timescale: medium term

Compulsory Purchase Orders

The Government says it wants to “improve the effectiveness, take-up and role of Compulsory Purchase Orders to help facilitate land assembly and infrastructure delivery”.

This is to be achieved in two ways, with very different timescales:

- “MHCLG will introduce further support and expertise to LAs to give greater confidence in using CPO powers and will consult on legislative reforms to speed up the decision-making process”.

- “The government intends to consult on: introducing statutory timescales for decisions; ending the automatic right to public inquiry; encouraging early agreements on compensations; and exploring the scope to remit more decisions back to LAs; as well as wider reform”

Timescale: short term for support, medium to long term for legislative changes

Footnotes:

[i] Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, Intervention on the London Plan

[ii] The previous Government's May 2019 response to the October 2018 consultation on planning reform, which included upward extensions - see paras 22-35

[iii] DCLG, Thousands more homes to be developed in planning shake up

[iv] IPPR Report Closer to Home (pp 36-37)

[v] Lichfields analysis of the 2018-based Population Projections

[vi] Regulation 10A of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 provides that local planning authorities must review their plans at least every five years to see if they require updating. Paragraph 33 of the National Planning Policy Framework sets out what the review should cover and when earlier review might be necessary and says that following the review plans should be updated as necessary.

[vii] The Rosewell Review: Independent review of planning appeal inquiries: report

[viii] Planning Practice Guidance, What types of area-wide local planning permission are there?

[ix] Lichfields Planning Matters, Housing Infrastructure Fund: The story so far….