Update 27 February 2025

New and updated Green Belt planning practice guidance was published on 27 February 2025. The Government had said the guidance would be published in January - hence the references to January guidance in the blog. The blog has been updated, in italics, to refer and link to the new guidance.

A more recent Lichfields Planning Matters blog, by Judith Livesey and colleagues, analyses the new/updated Green Belt guidance, which explains how to carry out Green Belt assessment for plan-making and how to consider it when decision taking. A further blog, by Dominic Holding, considers the implications of the NPPF on built heritage and archaeology.

________________________________________________

The flagship policy of the revised National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) is, arguably, grey belt. A concept first announced at the 2023 Labour Party Conference, grey belt policy has arisen from the Government’s acknowledgment that there is insufficient brownfield land to meet development needs. It also responds to calls to look to poorly performing Green Belt sites, before looking to develop other Green Belt and/or green field sites

[1].

The July 2024 NPPF consultation provided the first potential policy approach to development in the Green Belt, including a definition of grey belt. The published NPPF 2024 policy is significantly different to the consultation version. Changes to the grey belt definition itself and to the contributions or ‘Golden Rules’ that developments on certain Green Belt or former Green Belt are to make, are among those made in response to the consultation.

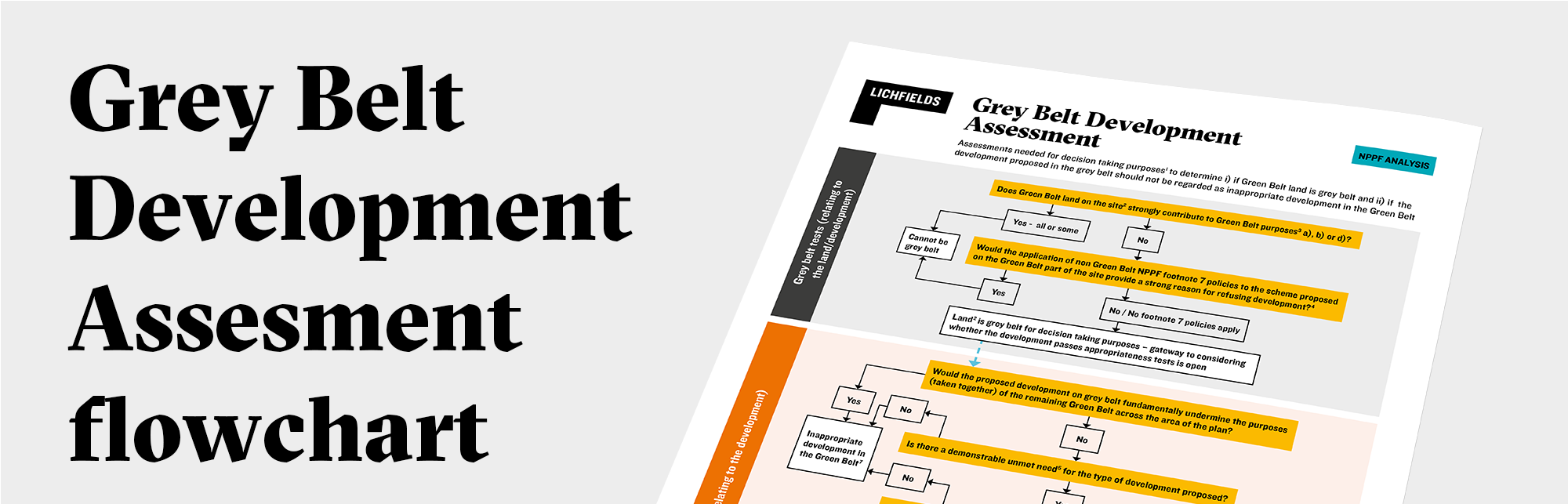

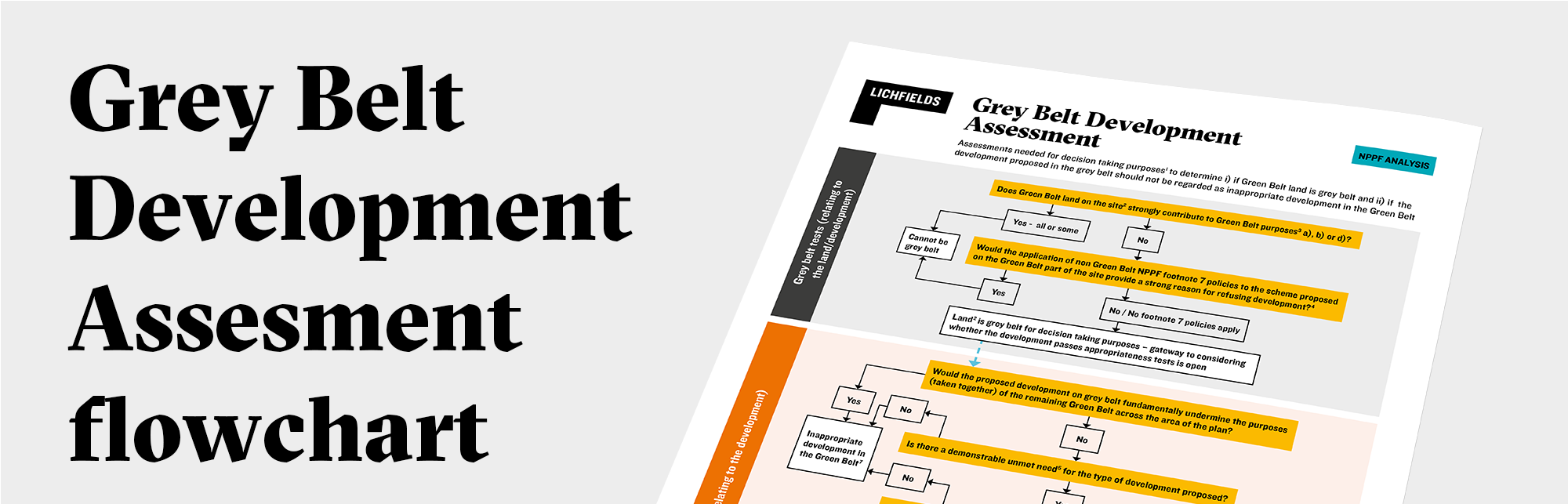

Lichfields has prepared a flowchart of the two test process towards establishing that a development proposed by application, on a Green Belt site, is not inappropriate, by virtue of being grey belt.

While the flowchart can be viewed in isolation to gain a general overview of the policy tests, this blog expands those tests, and the assessment steps within them, in terms of how they apply to decision-taking, rather than plan-making:

Stage 1 – Grey belt tests

Stage 2 – ‘Appropriateness tests’ – is the development ‘not inappropriate’?

The Government has acknowledged that there are challenges associated with these new assessments and guidance on various Green Belt and grey belt matters is expected this month. This blog mentions where guidance is promised on a specific element of the assessments–

and now includes updates, in italics, to refer to the new guidance.

Grey belt definition and two step test

The definition of the grey belt is in two paragraphs:

Grey belt: For the purposes of plan-making and decision-making, ‘grey belt’ is defined as land in the Green Belt comprising previously developed land and/or any other land that, in either case, does not strongly contribute to any of purposes (a), (b), or (d) in paragraph 143.

‘Grey belt’ excludes land where the application of the policies relating to the areas or assets in footnote 7 (other than Green Belt) would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development.

This definition creates a two-step test. The

first is a Green Belt contributions assessment, against three Green Belt purposes (rather than five in the consultation NPPF), which requires consideration of the land in question. The

second is an areas and assets assessment, which requires consideration of the development proposed.

The Government has explained that the grey belt definition deliberately includes land that is not previously developed “as we believe it is important that we also consider the development potential of land which, though it may be formally designated as Green Belt, no longer adequately serves the Green Belt purposes”.

Stage 1: Grey belt tests

Test 1: Contribution assessment – relating to the land

The Green Belt serves five purposes (para 143), which have not been amended and remain as follows (my bold, explained below):

-

to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas;

-

to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another;

-

to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment;

-

to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and

-

to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

To be considered grey belt, land will not strongly contribute to Green Belt purposes a), b) or d) - even if it performs well against c) and e).

Conversely, land strongly contributing to any of these three criteria would not be considered grey belt.

Therefore, the significant change, from the grey belt definition consulted on

[2], is that land that strongly contributes to c) assisting safeguarding the countryside from encroachment and/or e) urban regeneration, could be grey belt development, provided that land does not strongly contribute to purposes a), b) and d).

Furthermore, land that contributes to Green Belt purposes a), b) or d), but does not strongly contribute to any of those purposes, can be grey belt. (All subject to the protected assets and areas/footnote 7 assessment at Test 2, see below.)

Understanding whether or not land performs well in terms of preventing coalescence will be key. It will depend on the nature of the settlement to be extended. Further guidance will be needed to give an indication as to how towns are to be defined, so that there aren’t protracted debates, and resultant case law on the applicable towns or settlements to consider.

The Government has said that it will provide guidance intended to ensure a more consistent approach to the identification of grey belt land and how the performance of Green Belt should be assessed, among other things. (The 27 February Green Belt planning practice guidance sets out how to assess performance, but does not give an indication of how towns are to be defined. However, the new guidance is clear that villages should not be considered large built-up areas.)

Test 2: Protected assets and areas assessment – relating to proposed development

To be considered grey belt development, development that is proposed on Green Belt land, which does not strongly contribute to green belt purposes a) b) or d) (i.e. has passed Test 1 above), either:

-

does not fall within a footnote 7 asset or area; or

-

where, within a footnote 7 asset or area, the application of the footnote 7 related NPPF policies would not provide a strong reason for refusing development.

Footnote 7 is a footnote to paragraphs 11b and d of the NPPF, ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development', which lists certain assets and areas. Footnote 7 says:

The policies referred to are those in this Framework (rather than those in development plans) relating to:

The reference to footnote 7 within the grey belt definition makes clear that where the application of policies listed at footnote 7 would not give a strong reason for refusing or restricting development, that development is not excluded from being grey belt.

The reference to “strong reason for refusing” is a reference to a planning decision. Restricting in the context of a planning application would mean refusing at determination. There are references to restriction by condition in the NPPF, but restricting is the terminology used in para 11b(i), which also refers to footnote 7. Therefore, it is much more likely that the Government has replicated the terminology used in both paragraphs that refer to footnote 7 – refusing for decision making and restricting for plan-making. For this reason, we do not consider that planning applications on potential grey belt sites need to consider what restriction means.

The revised definition of grey belt (compared with the consultation version) has provided confirmation that land is not to be ruled out of being grey belt simply if it is a footnote 7 asset or area. But rather, where applicable, NPPF policy regarding those assets and areas will need to be applied to the proposal in question, in order to determine whether a site is grey belt or not as well as to determine whether a proposed development satisfies those specific policies. As published, this test will need to consider the development proposed, not solely the land. (In this respect, para 006 of the Green Belt guidance says, “In reaching this judgement [re whether or not footnote 7 policies provide a reason for refusal/restricting] authorities should consider where areas of grey belt would be covered by or affect other designations in footnote 7. Where this is the case, it may only be possible to provisionally identify such land as grey belt in advance of more detailed specific proposals”.)

At the end of Tests 1 and 2 of Stage 1 it will be concluded whether or not the proposed development site can be treated as grey belt land. The grey belt status of a site does not, of itself, provide a way forward for the proposed development – this comes at the end of stage 2.

Stage 2 – ‘Appropriateness tests’ – is the development ‘not inappropriate’?

Establishing that land is grey belt is the gateway to establishing if the development proposed might be ‘not inappropriate’, and thus – for applications - not required to make a very special circumstances case to clearly outweigh the Green Belt harms and any other harms,

[7], so that Green Belt policy should not be a reason for refusal.

Grey belt proposals that meet all the following criteria, as set out at para 155, should not be regarded as inappropriate development:

-

The development would utilise grey belt land and would not fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt across the area of the plan;

-

There is a demonstrable unmet need for the type of development proposed (defined in footnote 56 for housing); [and]

-

The development would be in a sustainable location

And if the proposal is for major development involving housing in the grey belt:

– d. The development would meet the Golden Rules

Grey belt land that does not meet the above criteria is still grey belt (in the Green Belt), but the proposal in question is either inappropriate development or it can be demonstrated via other NPPF paras, e.g. para 154g, that it is not inappropriate.

It is important to note that some Green Belt land, and/or the development proposed on it, might fall within the new grey belt, but this was already not inappropriate by virtue of an exception (now all consolidated at para 154). The para 154 exception sites do not need to be considered against the criteria at para 155 (grey belt appropriateness tests), because the exception has been determined by para 154; this outcome is not re-opened by para 155. Furthermore, para 155 begins by saying that that “development in the Green Belt should “also” not be regarded as inappropriate where[…]”.

Therefore, this blog considers that it is only sites that rely on passing the para 155 tests, in order to be considered not inappropriate development, that must pass the para 155 tests. Related to this, the scope of the limited infilling/redevelopment on previously developed land exception to inappropriate development (para 154 g)), has been expanded - including by the significant change of potentially applying to all development types, not solely where identified affordable housing need is met. The potential to benefit from this and other exceptions should be considered prior to looking to potential grey belt opportunities.

(The planning practice guidance says (our emphasis): “National policy also requires authorities to identify, where necessary, whether land is grey belt for the purpose of considering applications on Green Belt land. Where land is identified as grey belt land, any proposed development of that land should be considered against paragraph 155 of the NPPF, which sets out the conditions in which development would not be inappropriate on grey belt land”.)

The Golden Rules apply to major development involving housing, rather than major housing development. However, this phrasing reflects the definition of major development at Article 2 of the of the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015 with regard to “provision” and as such could mean that it only applies to residential development of 10 or more homes, which would also reflect para 65 “Provision of affordable housing should not be sought for residential developments that are not major developments, other than in designated rural areas (where policies may set out a lower threshold of 5 units or fewer)”. The alternative reading, that it applies to major commercial development - if even only one home is proposed, appears to contradict the intention of para 65.

(This alternative reading is unlikely to be the case, because the 27 February planning practice guidance refers to ‘major housing development’ throughout.)

What are the Stage 2 appropriateness tests for grey belt?

a) Not fundamentally undermining the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt

Based on the very limited number of appeals that consider grey belt since 12 December 2024, Inspectors have taken different approaches to addressing criterion a). For example, on

an East Hertfordshire appeal, the Inspector considered the relative impact of the scheme on the district’s Green Belt as a whole, rather than considering the development itself against the five purposes of the Green Belt:

“The Green Belt covers approximately one-third of the Council’s District and in that context, the limited extent of the appeal site and form of proposed development would not fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt across the district”.The Government says its January 2025 guidance will advise how the performance of Green Belt should be assessed, including how to ensure that parcels of land identified for development do not fundamentally undermine the purpose of the wider Green Belt.

This reflects a consultation outcome related to this test:

“There was agreement that further guidance would be needed on how to understand whether the development of a site fundamentally undermined the function of the Green Belt and how this was to be differentiated from how well the land fulfilled the Green Belt purposes”.

(The Green Belt planning practice guidance says, at para 008: “In reaching this judgement, authorities should consider whether, or the extent to which, the release or development of Green Belt Land would affect the ability of all the remaining Green Belt across the area of the plan from serving all five of the Green Belt purposes in a meaningful way”.)

b) What is demonstrable unmet need?

Criterion b), demonstrating unmet need for housing, is defined in footnote 56:

“the lack of a five year supply of deliverable housing sites, including the relevant buffer where applicable, or where the Housing Delivery Tests was below 75% of the housing requirement over the previous three years”.

There is no specified measure for demonstrating unmet need for non-residential developments, and there will not be for the foreseeable future, because the Government acknowledges the evidence for need of commercial or other development may differ depending on the development being proposed.

c) Establishing whether the development would be in a sustainable location

Criterion c) is that “the development would be in a sustainable location, with particular reference to paragraphs 110 and 115 of this Framework”. NPPF paras 110 and 115 provide policy regarding sustainable growth patterns and transport, cost effective, vision-led mitigation of significant highway safety and transport network impact and safe, well-designed development that reflects national guidance. The reference to these paragraphs in intended “to illustrate the importance that issues around transport have for considerations of sustainability”. Para 110 recognises that opportunities to maximise sustainable transport solutions will vary between urban and rural areas.

Similarly, the sequential approach to the release of Green Belt land must be considered in the context of paras 110 and 115 and an overall sustainability judgement, so that “more sustainable sites on higher performing Green Belt land (e.g. around train stations) can be brought forward without all Previously Developed Land and grey belt opportunities having to be exhausted first”.

It seems that Government would like this approach to apply as much to applications as to the allocation of sites (para 011 of the Green Belt planning practice guidance is clear on this point).

d) Golden Rules for major development involving housing -

Criterion d) requires major development in the Green Belt involving housing that is either:

-

on land released from the Green Belt in plans adopted after 12 December 2024; or

-

on Green Belt land and granted planning permission after 12 December 2024 (unless a s73 to a permission granted 11 December 2024 or earlier);

to meet the Golden Rules

[8], which are:

-

“affordable housing contribution requirements (see below)

-

necessary improvements to local or national infrastructure; and

-

the provision of new, or improvements to existing, green spaces that are accessible to the public. New residents should be able to access good quality green spaces within a short walk of their home, whether through onsite provision or through access to offsite spaces.

Subject to the transitional arrangements and not demonstrating a para 154 exception, the Golden Rules “should” apply to all major development involving housing in the Green Belt, whether proposed via application or site allocation – the Golden Rules are not solely for grey belt schemes.

Where a proposal complies with the Golden Rules, significant weight in favour of the grant of permission should be given (para 158).

The green spaces golden rule

The NPPF says that the improvements to green spaces required by Golden Rule c) should contribute positively to the landscape setting of the development, support nature recovery and meet local standards for green space provision or otherwise meet relevant national standards. If the land has been identified within a Local Nature Recovery Strategy the proposals should contribute towards its intended outcomes (para 159).

(The Green Belt section of the planning practice guidance sets out the contributions to accessible green space that should be considered, in respect of major housing developments. These include safe, visually stimulating spaces that meet local need, vegetated spaces and potentially blue spaces that are accessible free of charge, spaces that contribute to Local Nature Recovery Strategies. Conditions or planning obligations are to be considered to secure improvements, but it acknowledged that Community Infrastructure Levy funds could also be used.)

Planning practice guidance on Local Nature Recovery Strategies, also expected in January 2025, is to further clarify the role of Local Nature Recovery Strategies when it comes to enhancing the Green Belt.

However, the Government has already noted that access to green space will not be appropriate in all cases of commercial development. (The guidance expressly refers to major housing development, in the context of the green spaces Golden Rule.)

(Planning practice guidance on the Natural Environment was updated on regarding Local Nature Recovery Strategies (and plan-making guidance was updated to cross refer to it). In addition to the links to legislation and guidance that can be found there, see here for a recent Defra blog on the future Local Nature Recovery Strategies.)

The affordable housing Golden Rule

The Golden Rule for affordable housing sets a short term and long-term approach to establishing the affordable housing required.

Major development in the Green Belt involving housing:

-

should (in the short to medium term) contribute affordable housing 15 percentage points higher than the highest affordable housing requirement that would apply, capped at 50%/ applied at 50% if there is no local affordable housing requirement. Site specific viability assessment should reflect Planning Practice Guidance (para 157); or

-

should (in the medium to long term, once policies are updated) contribute affordable housing at the in line with “a specific affordable housing requirement or requirements”, required to be set out in a development plan

Accordingly, local plans are to set an affordable housing target for major development involving housing, whether on land released from the Green Belt or within the Green Belt.

The Green Belt affordable housing requirement should:

-

be set at a higher level than that which would otherwise apply to land which is not within or proposed to be released from the Green Belt; and

-

require at least 50% of the housing to be affordable, unless this would make the development of these sites unviable (when tested in accordance with national planning practice guidance on viability).

Local plans’ Green Belt affordable housing requirement may be set as a single rate or be set at differential rates. Local planning authorities may also set tenure mix in relation to the Golden Rules.

On a related point, vacant building credit does not apply to major development on land within or released from the Green Belt (footnote 30).

The Government intends to review the planning practice guidance on viability and will be considering whether there are circumstances in which site-specific viability assessment may be taken into account, for example, on Previously Developed Land. The Government has not committed to publishing the revised viability guidance alongside the Green Belt guidance, which the Government says will be published during January 2025.

(The Green Belt planning practice guidance refers to the viability guidance regarding the Golden Rules, which was published in December 2024. It makes no other mention of viability or current approaches to viability assessment of Green Belt sites and no mention of affordable housing. Updated viability guidance continues to be expected in the coming months, but not imminently.)

Review of assessment outcomes

A grey belt proposal that meets the appropriateness tests, should not be considered inappropriate development. This significant change to national policy means many more Green Belt sites will be now be open to (re)appraisal for development. My colleague Phil McCarthy has considered this in the

context of renewable development.

While grey belt policy will create new opportunities, for some sites, complex considerations will belie the seemingly straightforward test questions.

As the flowchart shows, there are several steps to be followed, across the two tests, to determine whether or not a site in the Green Belt should be considered grey belt. If a site is grey belt, the advantages of that status would arise from also passing the appropriate tests, in order to be considered not inappropriate development. For many sites, each step will require a detailed, subjective, assessment to be undertaken.

As noted above, for this reason, any opportunities to meet the expanded para 154 exception test should be considered prior to making a case for a grey belt proposal.

Where land is not grey belt, or development is considered (by the developer and their team) likely to be inappropriate, then alternative routes to securing permission should be explored, notably by considering the prospects of a very special circumstances case.

Of course, decisions are to be made in accordance with the development plan unless material considerations indicate otherwise. NPPF grey belt policy is now a material consideration in the determination of planning applications.

In its response to the July NPPF consultation, the Government has set out its position on how grey belt policy relates to the development plan: “We fully support a plan-led system. However, we believe that it is necessary to allow development on suitable grey belt land through decision making (in line with relevant triggers), in order to address the housing crisis and ensure other development needs are met”.

The NPPF says that where a proposal complies with the Golden Rules, significant weight in favour of the grant of permission should be given. This, together with the thrust of national policy, including the Written Ministerial Statement

[9], shows that now is the time to assess the development opportunities of low performing Green Belt sites – whether previously developed land or not.

Footnotes

[1] Grey belt land is also Green Belt land. Green field land that is not in the Green Belt cannot be considered grey belt.

[2] Consultation draft definition of grey belt, which was not taken forward, for reference only:“Grey belt: For the purposes of plan-making and decision-making, ‘grey belt’ is defined as land in the green belt comprising Previously Developed Land and any other parcels and/or areas of Green Belt land that make a limited contribution to the five Green Belt purposes (as defined in para 140 of this Framework), but excluding those areas or assets of particular importance listed in footnote 7 of this Framework (other than land designated as Green Belt)”.

[3] Habitats site: Any site which would be included within the definition at regulation 8 of the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 for the purpose of those regulations, including candidate Special Areas of Conservation, Sites of Community Importance, Special Areas of Conservation, Special Protection Areas and any relevant Marine Sites.

[4] In determining an appeal re a temporary 49.35MW battery energy storage facility, in Walsall, the Inspector noted that he considered the reference to para 189, in footnote 7, to be typographical error. The Inspector considered that the correct reference should be to paragraph 194, and this view appears to be correct, as it reflects both NPPF 2024 and the consultation draft NPPF: “Para 194. The following should be given the same protection as habitats sites: a) potential Special Protection Areas and possible Special Areas of Conservation; b) listed or proposed Ramsar sites71; and c) sites identified, or required, as compensatory measures for adverse effects on habitats sites, potential Special Protection Areas, possible Special Areas of Conservation, and listed or proposed Ramsar sites”.

[5] Reference to Green Belt in footnote 7 has been removed from this list, as per the grey belt definition

[6] Footnote 75 “Non-designated heritage assets of archaeological interest, which are demonstrably of equivalent significance to scheduled monuments, should be considered subject to the policies for designated heritage assets”.

[8] Traveller sites will not need to meet the Golden Rules

[9] The Written Ministerial Statement, while a statement of policy doesn’t directly follow the steps in the NPPF, which are more technical.