I’ve previously penned my

thoughts on how tall buildings and greater density can help alleviate the housing crisis in an urban context, so one might think that I ought to be supportive of the Government’s proposed move to introduce minimum density standards. However, helpful they may seem, with a laudable intent, experience tells me that density standards do need to be treated with a degree of caution.

Density might be a dirty word in some NIMBY outposts, but it’s just a number at the end of a design process. Whether density is low, high, somewhere in the middle, good or bad, it is all relative and it shouldn’t really matter provided a site’s development potential has been optimised. To optimise development on a site naturally follows a robust assessment of its capacity taking into account development management considerations (such as heritage, townscape, daylight/sunlight), surrounding context and character and transport accessibility.

As far back as PPG3: Housing (2000) local planning authorities have been urged to avoid housing developments at low densities (below about 30 dwellings per hectare net) and to encourage housing that makes ‘more efficient’ use of urban land, including achieving 30–50 dwellings per hectare net on suitable sites. Twenty-five years on, here we are with a newly proposed NPPF advocating minimum densities of 40dph or a higher figure of 50dph around train stations. If we are serious about solving the housing crisis then perhaps we ought to be more aspirational, certainly on urban sites where there is clear potential to optimise density. The same approach to optimising density can be applied in other locational contexts, for example suburban or rural (including Green Belt), as we need to develop such land responsibly. There is, however, a need to acknowledge and respond to market indicators and evidence of housing need in a specific area – this inherently has an influence on development typology and therefore density. What we cannot risk is the NPPF approach to density culminating in half-measures that fail to make a dent in the housing emergency.

The consultation paper does elude to a wider debate on the issue, stating that “For development around well-connected stations, we are proposing a minimum density requirement of 50 dwellings per hectare within the net developable area of the site. We consider this will be sufficiently ambitious in some locations, particularly locations outside of settlements, and will act as the minimum requirement for other locations. For more urban locations, we would expect higher densities to be achieved, and are interested in how we could set clear expectations for more ambitious minimum density requirements in our urban cores – including how these locations should be defined. We also acknowledge that other public transport modes, beyond trains and trams, could support minimum residential density standards.”

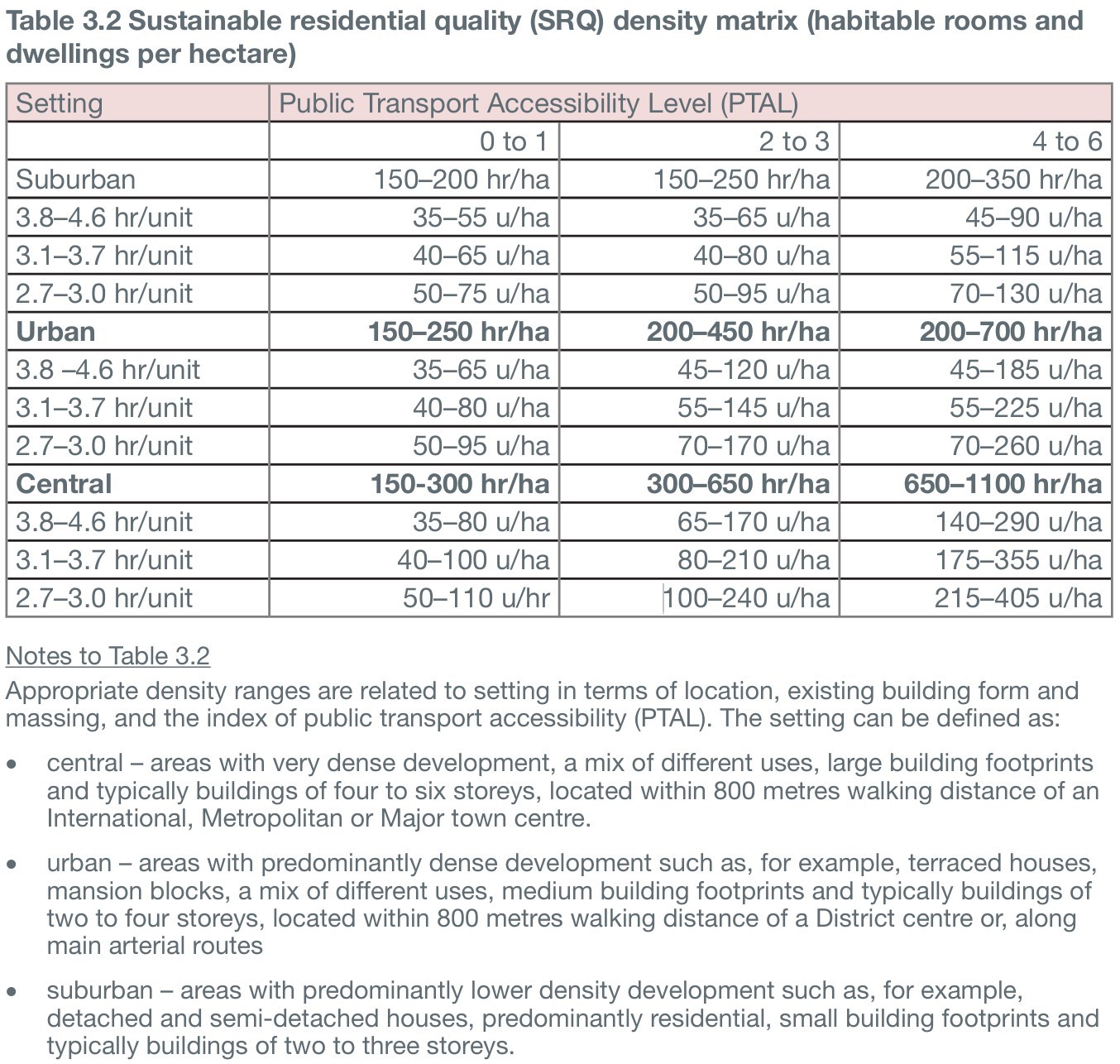

In the Capital, the GLA has previously used a density matrix, first seen in 2004 London Plan. Originally known as the Sustainable Residential Quality Matrix, it was a tool that linked density targets to a site location and transport accessibility. Makes sense, right, but the matrix was often criticised for being inflexible (colleagues here raised such

concerns ten years ago), and when it came to higher density schemes, it was used by objectors and some officers to seek moderations in height (as each range had a cap) which drove down housing numbers. It was subsequently discarded in the 2021 iteration.

Table 3.2, London Plan 2015

In place of the density matrix, the GLA adopted a design-led approach to site optimisation. Following a design-led approach often adds more subjectivity and negotiation into the pre-app process, but I would speculate that whilst there was already a growing trend for taller buildings coming forward in London each year (see NLA’s tall building survey data since 2014), the design-led approach results in better outcomes – higher quality contextual design and more homes. Our recent work at Borough Triangle for Berkeley is a great example of what can be achieved. In urban and some suburban areas, a minimum density is rarely required from a developer perspective, as the market is incentivised to deliver as much development as possible, often in flatted typologies, notwithstanding the recent Building Safety Act and increasing construction cost implications as you reach a certain height.

Borough Triangle, London

Image credit: Berkeley Group Plc

It’s not only London that has tested the use of a density matrix – Salford’s adopted local plan (LP H3) Housing Density has a matrix with minimum requirements based on locations in a designated centre or the distance from a transport node (for example, 200 dph (net) in city centres or within 400m of certain stations). Bristol was recently consulting on a new plan containing a minimum net 50dph target with higher minimums in inner and city areas (100 and 200 dph respectively).

However, as mentioned, the approach in suburban or rural areas may differ where saleability of the right product often drives developers development typology – why would you build higher density townhouses or apartments in areas where the demand is for detached homes? The application of a minimum density standard that uses locational criteria, for example within a railway station in the countryside, does run the risk of dictating what typologies come forward in certain locations, and by association, the future demographic of that specific area. Policy intervention is one thing, but we need to ensure it reflects the ability and will of the market to deliver.

So, the question is, if we are to solve the housing crisis is a minimum density threshold the answer and whether, in reality, would it really deliver more homes? I’m not so sure. A minimum density may help guard against objections to applications, but the various professional design teams, advisors and agents, developers and officers ought to be capable of arriving at a suitable density for each site or area, having regard to a multitude of factors which, when put together, would deliver an ‘optimised’ development for that site. From my experience, it is rare that we walk away from a planning process feeling that much was left on the table. We should, therefore, have a national policy presumption that all development proposals should be ‘optimised’ for housing delivery, unless exceptional circumstances apply. This could form a widened definition or explanation of what ‘making efficient use’ of land really means.

Turning to the draft NPPF itself, draft policy L1 1a iii. proposes setting minimum residential density standards for town centres and for locations that have a high level of connectivity, where this can support more effective land use, but it does not chime with the requirements of policy L3 (achieving appropriate densities, see below). Higher density in town centres is a no-brainer, but what about regeneration or opportunity areas which should aspire to higher densities in the interests of sustainability, or other parts of a settlement that have planned infrastructure investment? What about the new towns – should they set a new benchmark? If the ‘catch-all’ of this policy is anywhere with a “high level of connectivity” then that should be clearly defined, and include areas that will have high connectivity in the future. The Department for Transport launched a

Connectivity Tool in June 2025 so why not adopt its scoring system on a national basis?

In fairness, the draft NPPF consultation paper does start to ask the right questions, reminding us that it’s not all a question of density, but often an intricate patchwork of considerations before reaching a point of sustainable development: “identifying whether minimum density standards should be set for other parts of the plan area, especially where there are opportunities for intensification. It may be appropriate to set out a range of densities that reflect the identified need for different types of housing, local market conditions, the availability of infrastructure and its scope for improvement, the importance of securing well-designed, attractive and healthy places, and the desirability of maintaining an area’s prevailing character or of promoting regeneration and change.”

Conversely, draft policy DP3 (Key principles for well-designed places), at 1a, seems to suggest that we shouldn’t be too concerned about context at all as it should not preclude innovation and change, especially where an increase in scale or density of development is justified.

So back to draft Policy L3: Achieving appropriate densities (my comments in bold):

- Development proposals should make efficient use of land, taking into account the identified need for different types of housing and other development, local market conditions, the availability of infrastructure (including sustainable transport options) and its scope for improvement, a site’s connectivity and the importance of securing well designed, attractive and healthy places. Nothing new here so why not replace ‘efficient use of land’ with a more definitive requirement to ‘optimise development capacity’ of land for identified needs as this appears to work in London?

- Within this context development proposals for residential and mixed-use development within settlements should contribute to an increase in the density of the area in which they are situated. The existing character of an area should be taken into account, in accordance with policy DP3, but should not preclude development which makes the most of an area's potential. This is a positive step forward – increasing density in every settlement (not just town centres or areas with high levels of connectivity), and take account of context but don’t be restrained by it.

- Minimum densities for residential development proposals are appropriate in locations which provide high levels of connectivity to jobs and services. Where development proposals for housing or mixed-use schemes are within reasonable walking distance of a railway station, a density of at least 40 dwellings per hectare should be achieved within the net developable area of the site, or 50 dwellings per hectare where the station or stop is defined as ‘well-connected’. So it’s minimum densities in town centres and locations that have high levels of connectivity (set locally through local plans), its increasing densities in settlements (again set locally), but it’s a specific minimum density (set nationally) for sites within walking distance of a station? That station should be well-connected, (which has its own definition linked to frequency of rail services), which is a different thing to a site with high levels of connectivity (as that doesn’t have a definition at all). It’s starting to get complicated, which is exactly the opposite of what we need from a national policy.

- Development proposals that do not make efficient use of land in accordance with this policy should be refused. There aren’t many refusal directions in the draft NPPF, so this one is quite serious – meet the minimum density requirements set at a local level, or the station-specific requirement set nationally, or be refused, effectively. It again begs the question whether using minimum densities is too blunt a tool.

In summary, a well-intentioned proposal, but there are some further issues to consider and plenty of constructive debate to be had. From my perspective, whether minimum density standards are the right approach and whether they will ultimately deliver all the extra homes we need is questionable. As we now know, the NPPF changes often enough to enable us to alight and change track, but the housing crisis means we cannot take a wrong turn. If we are going down this track then we could give lofty density ambitions a try in certain contexts and see whether it has the desired effect. To my mind, if we are going to use density as the parameter, be brave. Set aspirational minimum targets (with an exceptional circumstances caveat to avoid refusals), be really clear on locational and connectivity criteria, and avoid any ambiguity over what the priority is – homes for all, quickly.

Courtesy of ChatGPT, the image below epitomises optimised residential development density (not bad, eh):