Among the various changes proposed by the Labour Party in its

2024 manifesto was to

“reform and strengthen the presumption in favour of sustainable development” as part of a package of measures to “

get Britain Building again”.

When it comes to deciding on planning applications, the current National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) presumption in favour of sustainable development (Para 11) ("the presumption") is intended to operate in such a way that, where a proposal does not accord with an up-to-date development plan, and there are no relevant local plan policies or those that exist and are most important are out-of-date, permission should be granted unless national policies restricting development provide a clear reason to refuse development or “any adverse impacts of doing so would significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits, when assessed against the policies in this Framework taken as a whole.”

The original presumption – introduced by the 2012 NPPF – had been a powerful trigger for boosting approvals of development, particularly housing in the period 2013-2016

[1] (see Figure 1). But following the policy flex in 2017, many perceived that it was becoming less effective, with a gradual reduction in permissions and approval rates (See Figure 1). A series of legal judgments clarified interpretations of policy that were seen by some as diluting the original force of the policy, and research in 2019 found that:

“Fewer than one in five of the 67 major housing appeals where the titled balance was applied in the first nine months of 2019 were successful”[2]. Assessing the prospects of securing approval on sites became more difficult, with decision taking (weighing harms vs benefits, even when tilted) often being said to be a lottery, with reductions in the number of applications and appeals submitted.

Figure 1 Major Residential appeals 2011/12 – 2023/24

Source: PINS / Lichfields analysis

Among the reasons why policies might be out of date – thereby triggering access to the presumption for decision taking purposes - has traditionally included the failure of a LPA to demonstrate a five-year supply of deliverable housing land. In the case of applications for residential development, access to the presumption had narrowed as a result of the

December 2023 changes to the NPPF, with the consequence that the proportion of LPAs unable to demonstrate a five year supply dropped from 39% to 26%

[3].

In this context, the new Government’s intention to reform and strengthen the presumption carried some promise. However, the NPPF

consultation proved something of a curates egg:

- There was little practical change to the essence of the presumption, particularly the titled balance, which retained its current formulation;

- There was clarification in terms of policies that can be considered out-of-date as expressly relating to the ’supply of land’, e.g. those that set a requirement, allocations and allow for windfall development;

- The changes state that in applying the titled balance, particular attention is drawn to NPPF policies on the location and design of development and affordable housing considerations, but without expressly explaining how;

- Access to the presumption has been broadened by virtue of the reintroduction of the five-year land supply measures and increased Standard Method which would likely result in 65-85% of LPAs being affected; and

- The measures around Grey Belt would make it more likely that development in Green Belt would not be restricted by part c) of Para 11. (Albeit there are some concerns around the 'golden rules' and possible reforms to BLV)

So access to the presumption is broadened, elements of it have been clarified, but outside Green Belt it is difficult to say the presumption has been 'strengthened’. The perceived high level of discretion or uncertainty - such that two planning professionals might apply the presumption and reach different conclusions on the same application - remains. Might this uncertainty limit the effectiveness of the NPPF in achieving the immediate boost to development on which its growth mission depends?

To explore the issue, we have updated some analysis originally carried out in 2018 looking at housing appeals on residential proposals. This had identified a high degree of discretion in decision taking, particularly focused on what happened when applications were refused by elected Councillors against the recommendation of planning officers.

Housing appeals, what has been happening?

Refused for Good Reason (2018)

The 2018 research

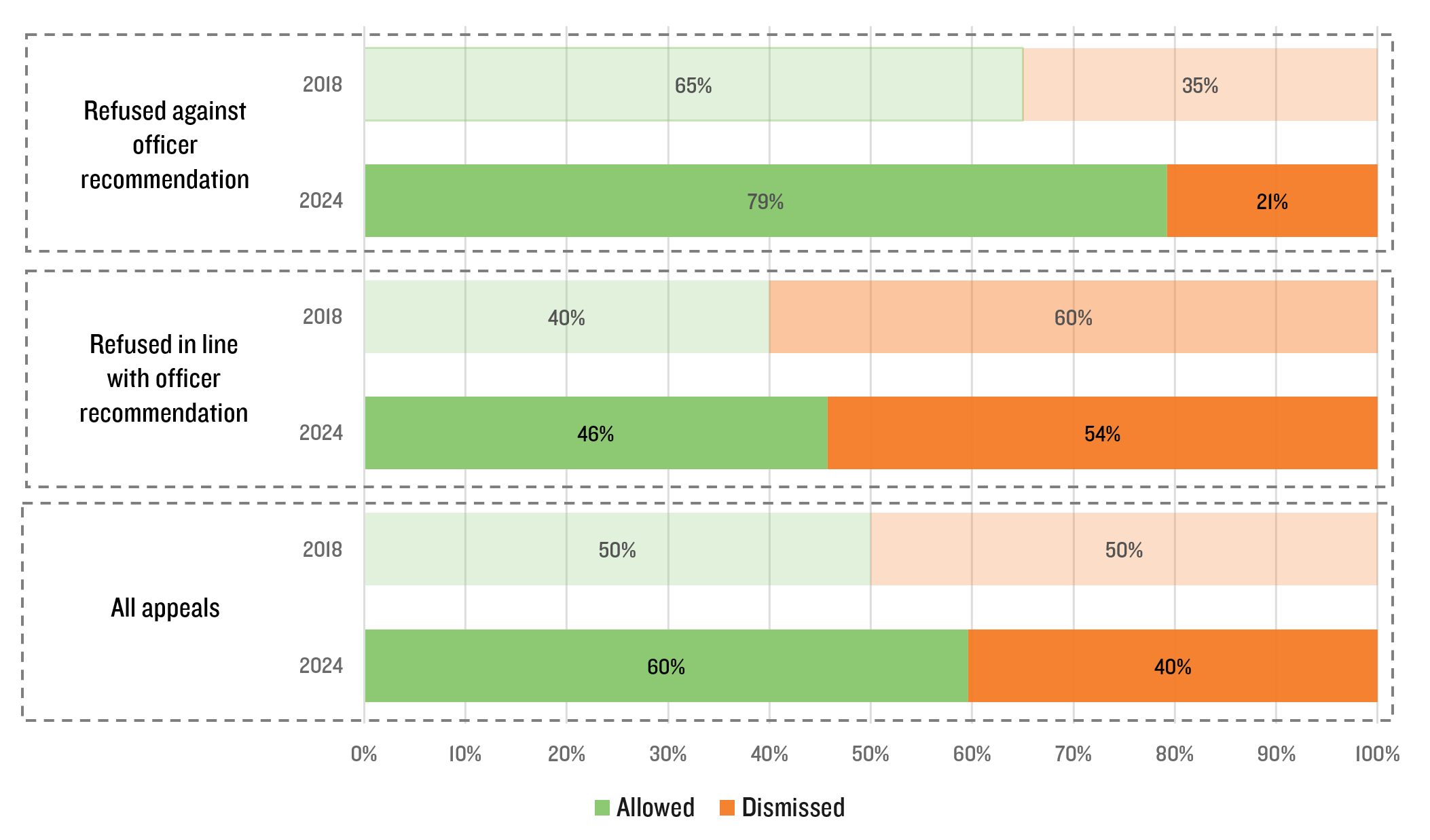

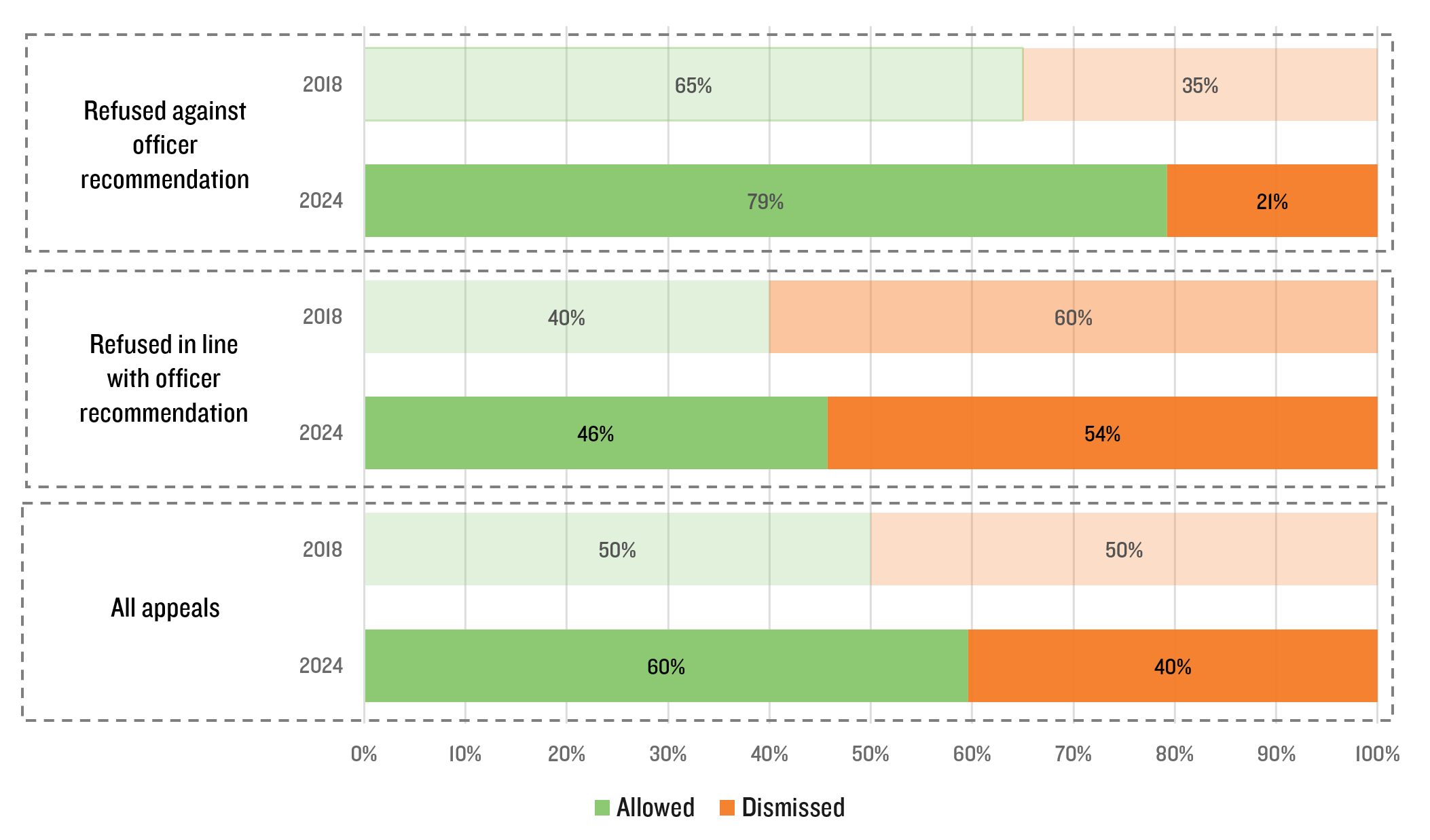

Refused for good reason? looked at 309 appeals for residential proposals of over 50 residential units decided in 2017

[4] to identify those that had a planning officer recommendation for approval before being refused by elected councillors. It found that 78 appeals (25%) were refused despite an officer recommendation for approval. Of those, 65% were then allowed but the corollary was that in 35% of cases, councillors were ‘justified’ in overturning the officer recommendation by virtue of the Inspector dismissing the appeal. For refusals made in line with officer recommendations, 40% were allowed. The research interrogated the reasons for refusal on each of these 78 appeals. It found that where appeals included reasons for refusal related to a highly technical matters (such as highways impact) the percentage of allowed appeals was generally higher than those which contain reasons for refusal where matters and issues were more subjective (e.g. landscape). This showed that on issues where a decision maker can exercise their judgment, the overall decision is less certain.

Appeals analysis 2024

To update this analysis, we looked at 640 planning appeals

[5] for developments including at least 50 residential units in England

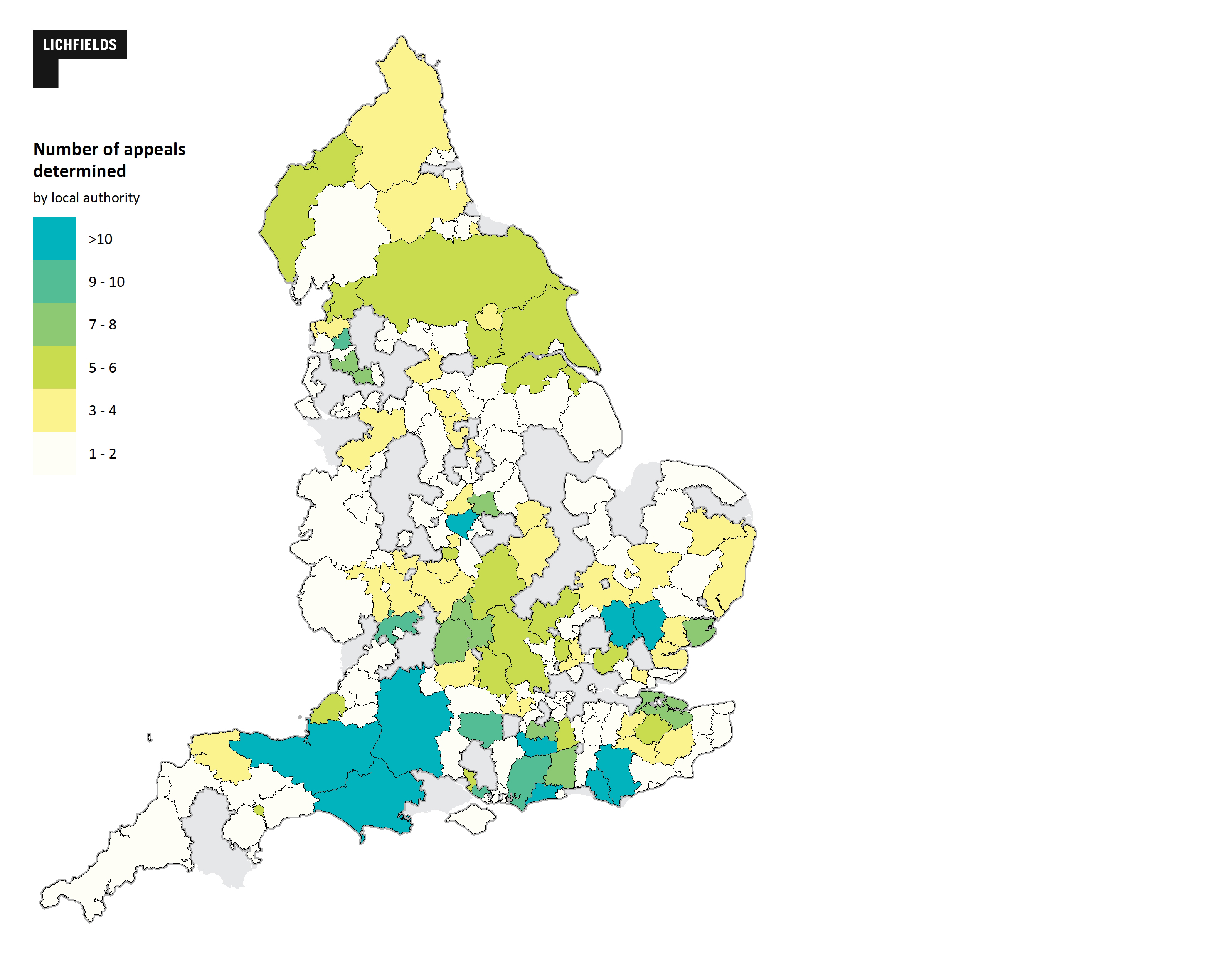

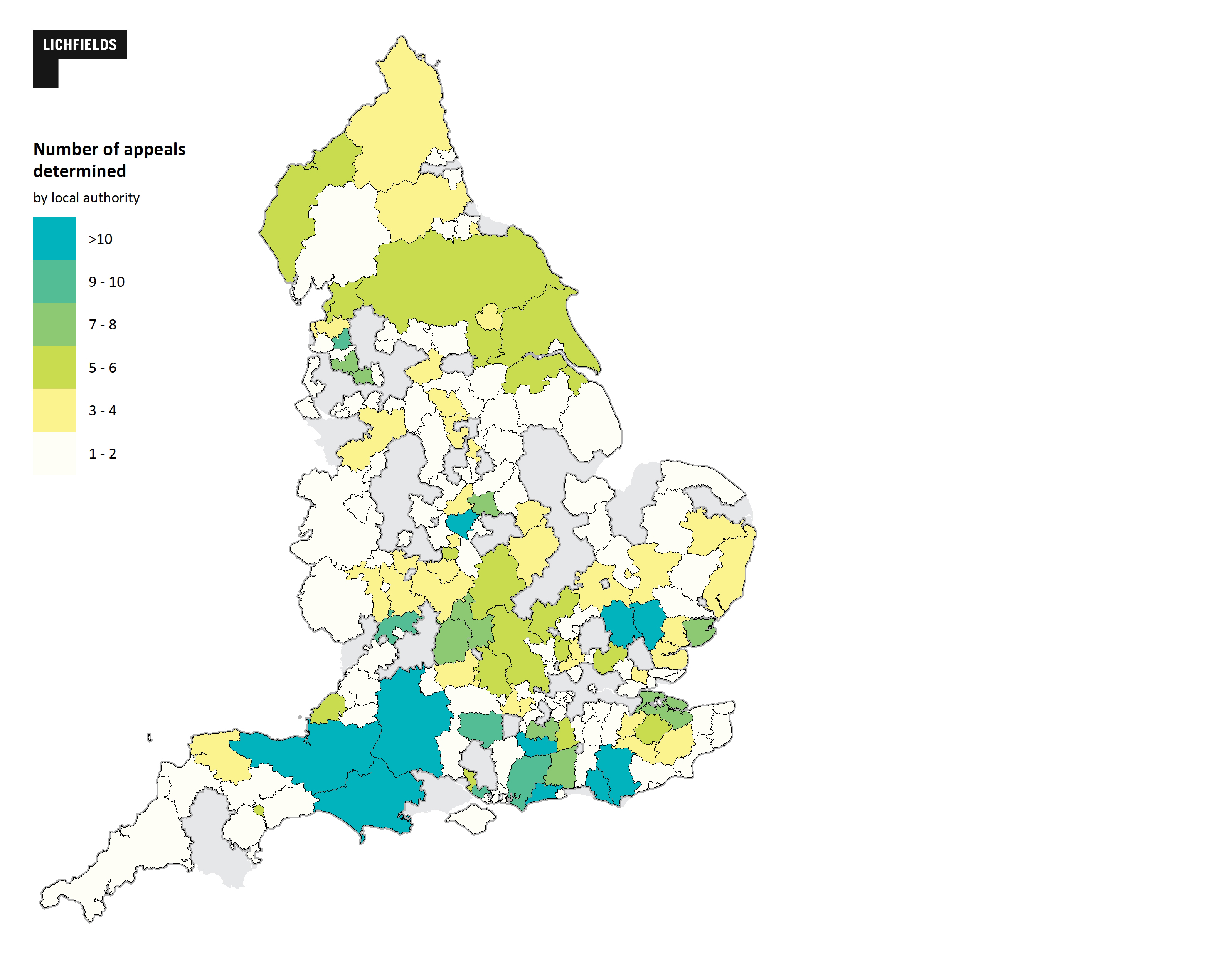

[6] from January 2021 to August 2024. A geographical spread of the appeals is set out below in Figure 2.

Figure 2 LPA locations of residential appeals analysised

Source: Lichfields analysis

Of significance is that the 309 appeals (306 in England) for just under 50,000 units in the single year (2018) compares to 639 appeals and 105,000 units for the 32-month period of the new research (an annual average of just under 240 appeals or 40,000 units), showing the rate of appeals has declined by around 20-25% compared to the earlier period, reflecting perhaps that the propensity to appeal (or indeed to apply for permission in the first place) has reduced. This is supported by MHCLG and PINS permission and appeal data (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Dwellings granted permission by LPA and at appeal

Source: PINS / MHCLG / Lichfields analysis (data sets from different sources so may not match)

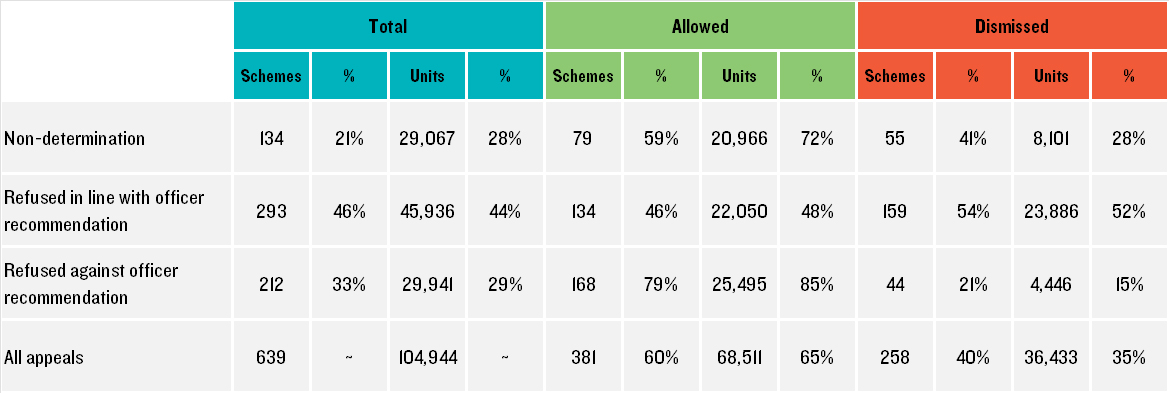

Of the 639 appeals we found that 21% were appealed against non-determination, 46% against an officer refusal and 33% by a refusal by planning committee contrary to officer recommendation

[7]. On determination, our key findings are that of those appeals which were pursued against an officer refusal, 46% were ultimately allowed. Where an appeal was pursued with a refusal contrary to officer recommendation, 79% were allowed. When looking at the percentage allowed by number of units, the figures are 48% and 85% respectively.

Table 1 Overview of appeals analysis (50+ unit residneitial schemes determined January 2021 to August 2024)

Source: Lichfields analysis using COMPASS

The two key highlights are:

- In 46% of cases where an professional planning officer recommended refusal, a planning inspector exercising their professional discretion disagreed and approved the scheme; and

- In 21% of cases where a planning committee refused a scheme where an officer had recommended approval, the planning inspector disagreed with the LPA’s officer and dismissed the scheme.

Figure 4 shows these findings relative to the 2018 research[8].

Figure 4 Comparative approval rates for appeals

Source: Lichfields analysis

Our latest findings suggests that the reduced volume in appeals of schemes of 50+ units has been accompanied by a slight increase in approval rates and a reduction in the over-turning of officer recommendations to approve at appeal. However, discretion and judgement remains alive and well in the determination of appeals. This is demonstrated by the fact that:

- It remains possible in a large number of cases for two professional planning decision takers to come to two opposite conclusions on broadly the same set of considerations. Whilst planning appeals sometimes benefit from having some technical issues resolved by the time they are determined (which a LPA officer may not have had before them), it is also likely that decision makers are drawing different conclusions on:

- how a proposal performs against specific policy tests based on interpretation of technical evidence and the significance of any breach or compliance;

- The weights given to various material considerations when balancing harms versus benefits[9];

- The overall conclusion one reaches in the planning balance.

- Housing remains an often politicised matter at a local level, with more Councils in no overall control, and having clear national policy direction seems ever more important to achieve the necessary outcome.

- Although the balance has shifted further in favour of Inspectors siding with the original officer recommendations rather than the elected members’ decision, the 21% where the latter view prevails remains a relatively high level of uncertainty in a process that can cost hundreds of thousands of pounds.

There is a logic for Government to use its changes to the NPPF to address the ongoing level of uncertainty in decision taking when applying the presumption in favour of sustainable development:

-

There is a clear national imperative to increase the flow of planning applications for housing towards achieving the 1.8m consented homes that are necessary to approach building 1.5m homes by end of this parliament;

-

There is a low level of up-to-date local plan coverage, and an increased prospect of LPAs not maintaining a five year land supply, so the bulk of new permissions required to boost delivery will inevitably come ahead of new Local Plans and be determined against the policies of the Framework, including the Para 11 presumption. This is likely to place increased strain on a resource-strapped system in terms of exercising the discretion involved within an inevitably politicised system. More certainty will improve efficiency;

-

The high costs of making an application and running an appeal (for both appellants and Councils) means the increased volume of applications would ideally be determined positively by LPAs in the first place, with applicants having a clearer view up-front on the prospects of securing a permission before deciding whether or not to invest in an application.

Where does this take us?

This line of discussion might take one down the rabbit hole of zoning versus our so-called ‘discretionary planning system’. But given the Government’s commitment to evolution not revolution, the solution must lie within the current Framework, the formulation of the presumption itself, and the supporting policy scaffold on which it rests

The presumption was not a fundamentally new concept when introduced in 2012. Since 1949, a presumption in favour of development has generally existed in some form, but waxed and waned in strength, often alongside the changing emphasis given to the development plan.

Planners who have been round the block talk either wistfully or with regret about the so-called ‘double presumption’ that existed in the 1980s. In particular, Circular 22/80 from the then DoE sought to “ensure that development is only prevented or restricted when this serves a clear planning purpose and the economic effects have been taken into account”. It went on to say that LPAs are asked to “adopt a more positive attitude to planning applications; to facilitate development; and always to grant planning permission, having regard to all material consideration, unless there are sound and clear-cut reasons for refusal”. (emphasis added). Via Circular 14/85 this sat alongside a downgrading of the development plan to “but only one” of the material considerations taken into account.

The plan-led system remains, but for as long as the current stock of local plans are (or soon will be) out-of-date and not providing for the scale of housing supply that is needed in many locations, the presumption will need to do the heavy lifting in grappling with planning applications.

From the various discussions around the proposed draft NPPF, there is a strong sense that it has moved in the right direction if one has the objective of seeking a boost in housing supply. But it is inescapable that more could be done to increase the certainty over whether proposals that are in conflict with out-of-date development plan policies will or will not be likely to receive permission.

Potential solutions

Among the potential options that could be considered are the following:

- Making clear the policy goals: The consultation NPPF involves some micro-surgery to individual policy provisions to shift decisions along the branches of what is in effect an algorithmic decision tree. However, standing back, the overall narrative of the NPPF remains the same. There is no expression of the current problem (e.g. a housing and economic growth emergency), the Government’s diagnosis of the current system (such as our analysis here), what the Government intends the NPPF to achieve (e.g. 1.5m homes and the fastest economic growth in the G7), how that represents a shift from the previous policy, and how achieving these national missions will rely on the aggregation of individual decisions on plans and applications[10]. Yes, there are Ministerial Statements, but much better would be to hardwire this narrative into the NPPF itself, perhaps in a similar style to Greg Clark's introduction to the 2012 NPPF[11]. Doing so would have a bearing on judgements on the weight to be applied to the benefits of delivering housing (or other developments).

- Change the ‘tilted balance’ formulation: One way to ‘strengthen’ the presumption would be amending the wording used for paragraph 11d. For example, one might borrow from Circular 22/80 so the formulation is “always granting permission unless….” and/or maybe adjusting the tilt in sub-paragraph ii) so the threshold for harm outweighing benefits is moved from ‘significantly and demonstrably’ to an alternative adverb. Would ‘substantially’, ‘categorically’, ‘definitively’, ‘decisively’ or 'clear cut' better nudge the presumption towards approval in more equivocal cases? Alternatively, one might go down the harder route of the so-called ‘Builders Remedy’ seen in parts of the US, in which it is clear that qualifying development (e.g. that provides affordable housing, meets specific regulatory requirements and other specific NPPF policy tests) is to be approved.

- Attributing weights for key policies in the framework: One could also be more prescriptive on the weights given by the Framework to interpretation of different harms and benefits, rather than leaving this to the judgement of the decision maker. The current NPPF ascribes weight for some types of development[12], albeit with limitations identified in Bewley Homes plc v. SoS [2024] EWHC 1166 (Admin)[13] but arguably these are all relatively minor forms of development and do not collectively add up to the support necessary to deliver 1.5 million homes or turbo charge the economy.

The Framework is much bolder in ascribing clear weights to harms, with those to be applied in the balance for Green Belt harm, conserving and enhancing National Parks, the Broads and National Landscapes (previously Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty) and designated heritage assets all set as great or substantial[14].

Therefore, the NPPF could definitively prescribe weight to key benefits. For example ‘substantial weight’ could be given to delivery of new homes, to provision of affordable homes, and to the benefit of meeting the needs of specific groups. This would address the risk that LPAs and Inspectors recognise a shortfall against the Standard Method estimate of local housing need but seek to downplay the significance of that shortfall, perhaps by questioning the validity of the need for housing in their local area. It could similarly address the ambiguous proposal of the NPPF consultation to add the reference to location, design and affordable homes to para 11 d) ii.

- Address size relativity: Small sites can face the problem that when ascribing weight, some decision takers temper the weight of benefits to the size of the scheme. For example, a small housing scheme might be given only moderate or limited weight to housing benefits in the context of a deficit in 5YHLS, but the same approach is not adopted to the harms. In the context of the scale of housing need and the importance of SME builders scaling up, every unit counts and the Framework could usefully confirm this.

- Limit the weight given to harms on non-valued landscapes: Just as national policy is clear on the weight to be attached to protecting national and valued landscapes (and limiting the discretion for allowing development in these circumstances), it could be similarly clear that landscape and visual impact on a non-valued landscape[15] or harm to the intrinsic beauty and character of countryside should not be given more than limited weight for refusing development that meets unmet need and is otherwise well-designed and located. This would address the fact that our 2018 research showed ‘landscape’ is one of the more subjective areas of assessment that opens up discretion and uncertainty when applying the presumption.

Some or all of these measures (which in due course could be part of how NDMPs address decision taking when a local plan is out of date) could provide the extra nudge required for the NPPF to truly deliver on the Labour manifesto commitment to "reform and strengthen" and better align the Framework with the Government's bold objectives.

Footnotes

[1] The rolling annual number of homes granted detailed permission (including Reserved Matters approval) increased from 200k in 2012/13 to 300k in 2016/17 and hit 400k in 2019/20, with related outline permission likely to be 1-3 years prior.

[2] Carried out by Gladman, reported in Planning Resource here

[3] Based on the Planning Resource Housing Land Supply Index for September 2023 and April 2024. Planning estimates that the December 2023 NPPF resulted in 40 per cent of the country’s LPAs being exempt from the need to maintain a five-year housing land supply due to having an up-to-date local plan.

[4] Across England, Wales and Scotland, although only three were not in England.

[5] There are a number of omissions to schemes considered including appeals made in Uttlesford under 62As, discharge of conditions applications, Listed Building applications, applications to modify a planning obligation and applications solely for care, student and holiday lets. Where the scheme is mixed use, it is only included where there are at least 50 C3 units included. Where the appeal is conjoined, the two schemes are split out and considered separately, in line with the criteria set out earlier in this footnote.

[6] Given the focus on the NPPF issues, appeals in Wales and Scotland are not included, but only three appeared in the 2018 analysis in any event.

[7] To identify these appeals Lichfields has gone back to every officer delegated report (where the scheme did not go to planning committee) or Planning Committee report as appropriate to see what the case officer’s stated recommendation was for the Planning Committee.

[8] The 2018 research looked at England, Scotland and Wales, but only three of the appeals were outside England.

[9] One problem is where the weight given to ‘benefits’ of housing for smaller schemes are assumed to be moderate or limited because the scheme provides a relatively small number of homes, without also doing the same for harms, which are also likely to be proportionately small compared to a bigger scheme. A particularly egregious example is at APP/M3645/W/19/3227990 where (IR 17 - 21) scale was cited in giving only 'moderate weight' to the housing benefit of a proposal for four dwellings despite only a 1.06 year land supply, but 'significant' weight was given to the schemes impact on character and appearance, which proved decisive in dismissing the proposal.

[10] This will be important given the next few years will rely on decision taking rather than plan making to bring forward development.

[11] See pages i-ii of the 2012 NPPF here

[12] For example: a) Small and medium sized windfall sites within existing settlements for homes (great weight, para 70d); b) Supporting economic growth and productivity (significant weight, para 85, albeit noting the Bewley Homes v. SoS case); c) Create, expand or alter schools (great weight, para 99a); d) Suitable brownfield land within settlements for homes and other identified needs (substantial weight, para 124c); e) Repowering and life-extension of existing renewable sites (significant weight, para 163);f) Energy efficiency and low carbon heating improvements to existing buildings (significant weight, para 164); g) Benefits of mineral extraction, including to the economy (great weight, para 217); h) Development which reflects local design policies and government guidance on design and/or outstanding or innovative designs which promote high levels of sustainability (significant weight, para 139a and b).

[13] See judgment here

[14] For example: a) Any harm to the Green Belt (substantial weight, para 153); b) Conserving and enhancing landscape and scenic beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage in National Parks, the Broads and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (great weight, para 182); c) Designated heritage assets conservation (great weight, para 205).

[15] The definition of a valued and non-valued landscape is not included in the Framework, but arguably it should be. We note the broad points from case law that 1) valued landscapes do not have to be designated and 2) valued landscapes are not the same as popular landscapes. All landscapes are of value to at least somebody. To merit protection under national policy, there needs to be something more than the everyday.