O come all ye planners,

Joyful and aligned,

See the new framework,

Intended to be clear!

Twelve-week consultation,

Default “Yes” at stations,

Brownfield passports bring good cheer!

[1]In what is now an annual Christmas tradition

[2] (in which Government alternately publishes a version of the national planning policy framework either for consultation or adoption) a new NPPF has landed, this time for consultation with much-awaited national decision-making policies (NDMPs).

There is a significant body of proposed policy to digest and consider before one pontificates on the document as a whole, but this blog focuses on the structural architecture of the NDMPs (notably the timing of implementation and relationship with the statutory development plan) and the striking proposals to reform and strengthen the presumption in favour of sustainable development (“the Presumption”).

A daunting inheritance

When the Government took office over 18 months ago, it faced a daunting inheritance: our blog –

a new dawn has broken, has it not? – summarised the situation:

- The planning system was targeting annual housing delivery of just 259,000, with 75,000 homes a year needed in locations constrained by Green Belt

- Most areas had plans that were – or soon would be – ‘out of date’

- Residential planning permissions were well below what was needed to deliver 300,000 per annum

- Decision making on applications is unpredictable and most projects take at least 2-3 years to pass through planning – a finding reinforced by our subsequent research for LPDF and Richborough.

This led to the conclusion that a) net additions were unlikely to significantly exceed 200,000 in the short term and will need to ramp up; and, b) realistically, there would not be any great boost to supply arising from Labour’s proposals for strategic plans, new local plans, and new towns before 2029.

In combination, this meant that:

- any increase in housing delivery would need to arise from immediately encouraging the submission and approval of planning applications ahead of local plan, including in areas of Green Belt

- in view of the low starting point, the policy support for housing delivery to achieve this step-change would necessarily need to not only reverse the December 2023 NPPF, but go beyond the 2012 or 2018 iterations of the NPPF and be rapid in its effect.

The December 2024 NPPF and new Standard Method was a response to that agenda, and after a slow start,

[3] we are seeing some positive effects,

[4] notably in terms of the

Standard Method and pathway for development provided by

'grey belt'.

However, the core of NPPF policy - the Presumption – was little changed by last December 2024's document, despite the Labour Manifesto having included reference to it being “

reformed and strengthened”.

[5] In

our analysis of October 2024, we looked at how approval rates for schemes determined under the Presumption were falling and highlighted the significant levels of decision making uncertainty for:

- how a proposal performs against specific policy tests based on interpretation of technical evidence and the significance of any breach or compliance;

- The weights given to various material considerations in balancing harms versus benefits; and

- The overall conclusion one reaches in the planning balance.

In simple terms, in the period since 2012, effective decision making has developed a resistance to the Presumption much as bacteria has evolved to outsmart or resist antibiotics.

We made various suggestions for the next NPPF 'presumption' to aciheve its objectives for housing delivery, including:

- Be clearer on goals – hardwire the Government’s objectives into the NPPF;

- Strengthen the presumption – amend the wording to nudge presumption towards default approval;

- Prescribe weights for benefits – for example, substantial weight to key benefits like homes;

- Address size relativity - Confirm that housing benefits apply equally to small sites; and

- Limit Weight on Non-Valued Landscapes - make clear that harm to ordinary countryside or non-designated landscapes should carry only limited weight, reducing subjectivity and uncertainty.

Against these suggestions, this blog looks at how does the proposed changes to the NPPF measure up.

Further, there has been a recent debate (not rehearsed here) about whether new National Development Management Policies should be ‘statutory’ as per s.93 of the LURA, or can be non-statutory as per the current NPPF. The Government has settled on the idea that, at least for now, they should be non-statutory which means they operate much as per the current NPPF, within s.38(6) and the primacy of the development plan. In due course,

new streamlined local plans should create a simpler decision making framework, but with these some years away, does the new NPPF include the provision necessary to achieve the goals of streamlining and simplifying decision making against existing development plans?

We turn to each of these topics in turn.

Clearer goals? The new Introduction

The introduction to the new NPPF does not set out an overarching explanation for the national context within which the documents sits nor the goals of the changes. Rather, it provides a user guide to the new format structure and context of the NPPF. There is no reference to 1.5 million homes, the housing delivery emergency we find ourselves in, or the vital importance of economic growth to national renewal, or indeed to other important goals. This is a missed opportunity to ‘hardwire’ the national mission into decisions which will ultimately rely on the aggregation of individual decisions on plans and applications based on judgements and weightings.

However, the draft does acknowledge at paragraph 7 that “Some of these policies indicate how much weight the government would expect a particular consideration to be given, including cases where it is appropriate to give substantial weight to certain benefits, and the limited circumstances in which it is expected that permission would be refused.” This is a subtle but potentially clear steer that less judgement and more formulaic decision-making is being created through these proposed changes.

A Stronger Tilt? ‘Substantial’ vs ‘Significantly and demonstrably’

Gone is the current NPPF paragraph 11d); now we all hail the proposed national decision-making policies S3, S4 and S5.

The wording of the proposed new presumption has been strengthened. The proposal is now that development should be approved “unless the benefits of doing so would be substantially outweighed by any adverse effects”. Under the current NPPF, in applying the presumption, any adverse impacts of a development would need to “significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits” to be refused.

We note, firstly, that although perhaps making no practical difference, the subtle reordering of the sentence makes it more positive, i.e. the benefits would need to be outweighed, not adverse impacts having to outweigh benefits.

Secondly, the proposed wording changes the tilt from “significantly and demonstrably” to “substantially” which seems important. Clearly this may well find itself being interpreted by the courts, but on face value it looks like a strengthening: a stronger tilt towards approval.

A root through the dictionary indicates the word ‘significant’ equates to something that has meaning, is important or noteworthy. ‘Substantial’ equates to being of considerable importance, scale or value. When applied to ‘weight’ in the planning balance, 'substantial' sits above ‘significant’ in the scale. Arguably one might interpret this as nudging the planning judgment required in the presumption from something which is currently more discretionary, to something which is more quantitative.

The presumption is also proposed to widen across more circumstances (see Policy S3: Presumption in favour of sustainable development). An out-of-date plan or unmet need (via the Housing Delivery Test outcomes) or a lack of five-year housing land supply (5YHLS) is no longer determinative for the presumption to apply in many circumstances. As proposed, the presumption applies on all development proposal sites (including within settlement boundaries- see Policy S4: Principle of development within settlements), except for some circumstances for development outside settlement boundaries, as set out in Policy S5: Principle of development outside settlements.

Policy S4 Part 1, expects development proposals to be approved within settlements unless the benefits would be substantially outweighed by any adverse effects. It goes on at Part 2 to stipulate what these adverse impacts might be which is defined relatively narrowly.

Policy S5 provides a list of “certain forms of development which should be approved outside settlements”. Part h) relates to development for housing and mixed-use development which would be within reasonable walking distance of a railway station (on which we have a separate blog), but the most interesting is part j) which confirms the presumption applies to the:

“j. Development which would address an evidenced unmet need (including, but not limited to, development proposals involving the provision of housing where the local planning authority cannot demonstrate a five year supply of deliverable housing sites or scores below 75% in the most recent Housing Delivery Test), and where the development would:

- be well related to an existing settlement (unless the nature of the development would make this inappropriate) and be of a scale which can be accommodated taking into account the existing or proposed availability of infrastructure; or

- comprise major development for storage and distribution purposes which accords with policy E3.”

This means a housing development proposed outside a settlement boundary where there is lack of 5YHLS, or failure or unmet needs via the HDT outcomes, subject to parts i) and ii) above, should be approved. The Policy goes on at part 2 to stipulate (much in the same way as Policy S4) the circumstances when such development proposals are likely to be substantially outweighed by adverse effects, these include:

“situations where the development proposal would fail to comply with one of the national decision-making policies which state that development proposals should be refused in specific circumstances.”

[6]

Even more interestingly in the context of housing development, part 4 of the Policy refers to any other development proposals which do not fall within the categories a) to j) “should only be approved in exceptional circumstances, where the benefits of the proposal would substantially outweigh the adverse effects, including to the character of the countryside and in relation to promoting sustainable patterns of movement.”

No such reference is made to the character of the countryside in the context of housing and mixed-use development which would be within reasonable walking distance of a railway station nor housing where there is a lack of 5YHLS or a failure of the HDT. This does mean, that proposed residential developments outside settlements where there is a 5YHLS and no HDT failure, would only be approved in exceptional circumstances.

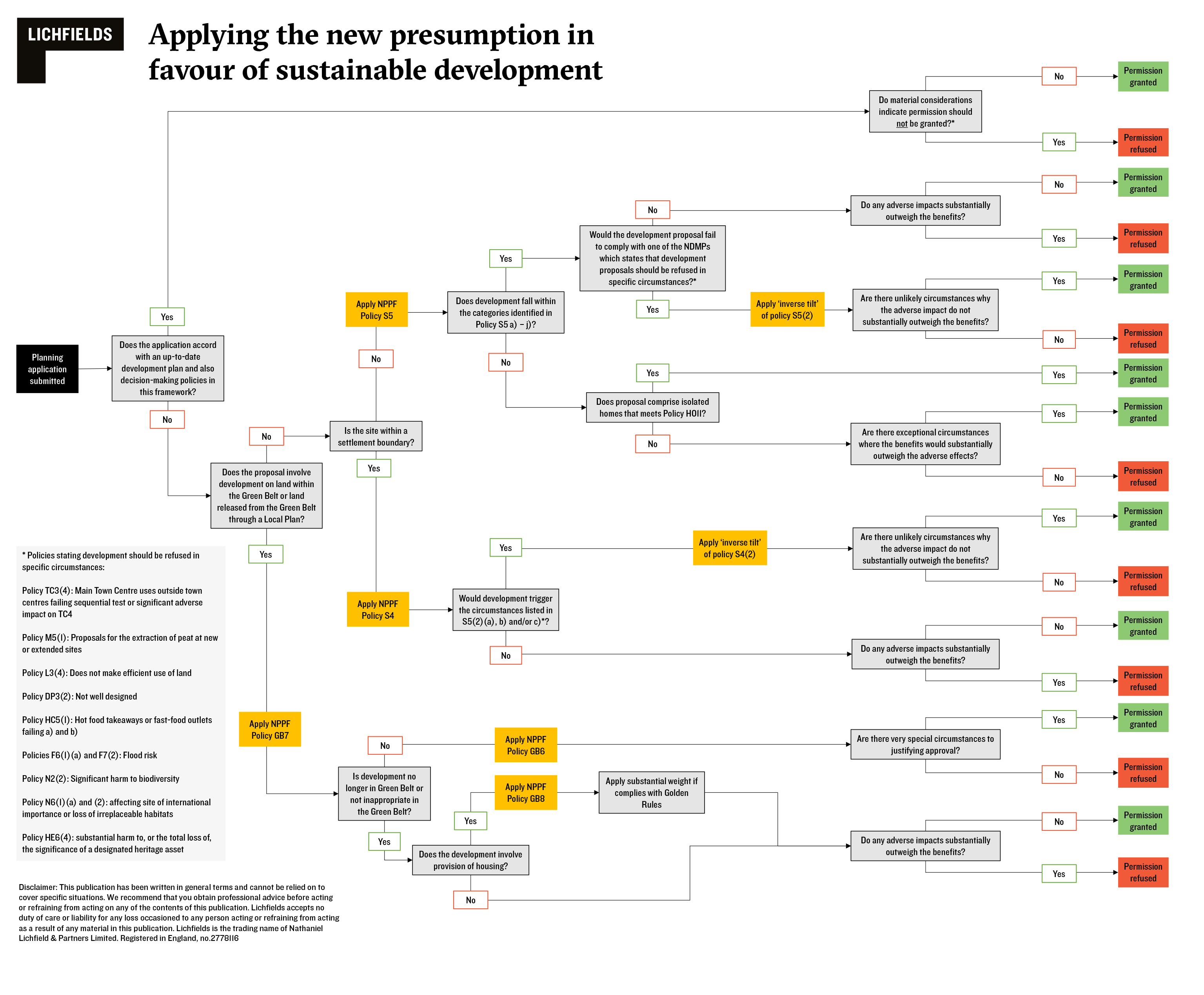

As a first cut, we have attempted to capture the clearer structure of the new presumption – and how it applies - within our decision tree below:

[7]The fly in the ointment for those seeking an NPPF that maximises the prospect of housing delivery, is the Annex A transitional provisions which at para 3 provide protection for Local Plans adopted in the past five years and which, in those areas, for the rest of this parliament will bake in the Gove-era housing legacy that the current Government is so keen to say it has replaced. We explore this further below.

Attributing weights to benefits and harms

At present, while the Framework ascribes some specific weights to some different harms and benefits, the majority are left to the judgement of the decision maker. Meaning the Framework is not collectively guiding decision makers on the support necessary to deliver 1.5 million homes or turbo charge the economy.

As set out earlier in this blog, these proposals go further and stipulate weight the government would expect a particular consideration to be given, notably for housing delivery and business growth.

Policy HO7: Meeting the need for homes, applies substantial weight to “providing accommodation that will contribute towards meeting the evidenced needs of the local community, taking into account any up-to-date local housing need assessment, and other relevant evidence (including the extent to which there is a five-year supply of deliverable housing and traveller sites, and performance against the Housing Delivery Test).” On face value, could this mean that a disagreement on housing mix might reduce the weight to be applied to housing delivery if what is proposed differs to an local plan evidence-based document? The extent of 5YHLS shortfall is often cited as a reason under the current system which impacts the weight to be given to the delivery of housing, but in the context of the national imperative for the delivery of homes, is this appropriate?

The current NPPF 2024 at paragraph 85 requires significant weight to be placed on the need to support economic growth and productivity. In the proposed NPPF, substantial weight is ascribed in Policy E2: Meeting the need for business land and premises to:

- “The economic benefits of proposals for commercial development which allow businesses to invest, expand and adapt; especially where this would support the economic vision and strategy for the area, the implementation of the Industrial Strategy, support improvements in freight and logistics and/or reflect proposals for Industrial Strategy Zones and AI Growth Zones;

- Benefits for domestic food production, animal welfare and the environment which can be demonstrated through proposals for development for farm and agricultural modernisation.”

How will the new Framework sit alongside the development plan?

The Government wants the Framework and new NDMPs to apply immediately from its publication in final form (Annex A: Implementation para 1).

The Annex (para 2) includes the provisions that:

"Development plan policies which are in any way inconsistent with the national decision making policies in this Framework should be given very limited weight, except where they have been examined and adopted against this Framework. Other development plan policies should not be given reduced weight simply because they were adopted prior to the publication of this Framework."

This is a strong indication that, within the framework of s.38(6), the Government intends the new NPPF, once adopted, to significantly reduce the salience of policies from existing local plans, including those that are yet to be adopted pursuant to the December 2024 NPPF transitional arrangements. This is arguably about as far as the Government might have been expected to go to within the current legal framework in pursuing the original idea behind NDMPs that originated in the 2020 White Paper and led to s.93 of the LURA.

That said, the new NDMPs clearly rely on existing settlement boundaries in existing local plans to define the circumstances in which policies S4 and S5 apply, so insofar as these are based on policies examined and adopted prior to any new Framework, these continue to attract significant weight for development outside settlement boundaries.

In this regard, it is of some concern that Annex A para 3 is clear that where ‘unmet need’ is a precursor for developing new homes under Policy S5(1)(j), this is determined based on HDT and the five year housing land supply performance against targets in adopted plan for five years from adoption, even if this is lower than the current Standard Method. Under current wording, this applies even to local plans prepared under previous versions of the Framework, including an estimated 39 Local Plans that have been adopted or remain under examination since July 2024 many of which were advanced by those Councils specifically in order to bake in lower housing targets than would now apply under the current Standard Method – in other words, produced to plan for fewer homes than would otherwise come forward.

Our analysis is that the housing targets across these 39 Local Plans are 15,411 homes less per annum than the Standard Method for those areas, and many will also avoid addressing unmet housing need from neighbouring areas. Annex A para 3 thus has a combined opportunity cost for housing delivery of around 77,000 homes across five years (plus any additional unmet need from neighbouring areas). The Government seeks to address this through its provisions at Annex D Para 9 with the 20% uplift on five year land supply. But amidst the general boldness of the new NPPF proposals, this seems a curiously tentative misstep.

Summary and Conclusion

The Government’s latest NPPF proposals introduce significant reforms aimed at accelerating housing delivery and simplifying decision-making with a clearer ‘rules-based’ approach. The specifics of individual policies will need to be considered further, and its effects will depend on how it is considered in the round for different forms of development and location. However, it represents, without doubt, the clearest and most coherent formulation of national policy for decades.

Ahead of new strategic and local plans emerging, the policies for decision making will have the greatest impacts on what actually happens on the ground. In this blog we focus on the Presumption and do not address the significant body of proposed policies focused on improving the performance of preparing and determining applications (Policies DM1 – DM7) which look to contain a number of welcome measures. There are also issues to be considered in terms of how ‘unmet need’ is demonstrated for economic growth in E2.

Central to the changes is a strengthened Presumption in which its structure and the tilted balance component significantly shifts from its 2012-era. Among the changes is amending “significantly and demonstrably” to “substantially outweighed,” creating a clearer tilt toward approval, and applying the Presumption across more circumstances.

The draft framework also prescribes substantial weight to housing and economic growth benefits and makes clearer which factors/circumstances will make refusal more likely, reducing some of the inherent subjectivity in planning judgments.

While NDMPs will operate non-statutorily within the current legal framework, they are intended to kick in immediately on formal adoption, with limited weight applying to existing Local Plan policies that are in any way inconsistent. It creates a fighting chance of addressing some of the delays and obfuscation that has driven up delays in planning decision taking since 2014, although other factors – notably around nature recovery and utilities - remain to be addressed.

Provisionally, we can say that the impact for housing delivery should be significantly positive (at least in the medium term) but that is moderated by the Annex A transitional provisions protecting recently adopted local plans, which risks constraining delivery in at least 39 separate areas by an estimated 77,000 homes over five years.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

National policy consultation 2025

Our web resource brings together Lichfields' analysis of the Government’s Draft National Planning Policy Framework consultation and other proposed reforms affecting the development industry

|

|

| |

|

|

Footnotes

[1] Thanks to Microsoft 365 Co-Pilot

[2] Recollections vary as to when this ancient custom began, but who can fail to remember the December 2022 NPPF consultation which downgraded housing targets.

[3] See for example this BBC analysis of the lagging indicator that is permissions

[4] See this Planning Portal Analysis up to September 2025

[5] See Labour Manifesto here

[6] These policies are:

Policy TC3(4): Main Town Centre uses outside town centres failing sequential test or significant adverse impact on TC4

Policy M5(1): Proposals for the extraction of peat at new or extended sites

Policy L3(4): Do not make efficient use of land

Policy DP3(2): Not well designed

Policy HC5(1): Hot food takeaways or fast-food outlets failing a) and b)

Policies F6(1)(a) and F7(2): Flood risk

Policy N2(2): Significant harm to biodiversity

Policy N6(1)(a) and (2) : affecting site of international importance or loss of irreplaceable habitats

Policy HE6(4): substantial harm to, or the total loss of, the significance of a designated heritage asset

[7] We won’t have got this right, so comments welcome!